In the United States, over 80% of the teacher workforce identifies as White (U.S. Department of Education, 2016) and, thus, may view the role of education (and their work as teachers) through a White lens (Moore, 2021). In contrast, student populations are increasingly diverse, and it is predicted that by 2024 White students in public schools will make up only 46% of the population (U.S. Department of Education, 2016).

For these reasons, as methods instructors in an elementary education program, we aim to support our primarily White teacher candidates in developing a theoretical lens of critical consciousness while they are learning to teach content. In this space, we guide them in how to teach for equity and justice by developing an inquiry stance to see, understand, and disrupt dominant discourses that misrepresent, omit, or silence youth of color or from lower income communities (Lee, 2008; Love, 2019). Through this humanizing and justice-oriented lens, our teacher candidates move from discussing one’s racialized identity in their foundations courses to learning to walk the talk in methods courses, which is the core of justice-oriented teaching.

Walking the talk means learning to let go, learning to listen, and learning — as empowered change agents—to promote more just and equitable student learning. To walk the talk, learning outcomes and associated activities need to be intentional and scaffolded to support teacher candidates who are new to teaching and still developing critical consciousness. This work becomes even more powerful when we, as instructors, collaborate to support teacher candidates in becoming change agents.

In this paper we describe how Mursion’s® mixed reality simulations (from here “simulations”), supported teacher candidates in beginning to walk the talk at our midsized university in the Midwest. This work began as a small study situated within our elementary mathematics and social studies methods classes to understand how simulations supplemented field experiences during the global coronavirus pandemic. However, we found lasting benefits that extended beyond an immediate need for field placements. Simulations not only augmented our candidates’ field experience, but they also gave us a window on their developing practice, specifically their development as teachers committed to becoming change agents enacting just and equitable learning.

This study is significant because it supported us to imagine, or reimagine, our teacher education space as a community of praxis (Schiera, 2021) seeking to converge critical (e.g., Freire, 1970/2011) and social (e.g., Lave, 1991) learning theories in a practice-oriented way. While much has been written about the importance of weaving issues of diversity, equity, and justice throughout teacher preparation, there are fewer examples of how to support teacher candidates in becoming justice-oriented teachers as they hone core teaching practices during methods coursework.

Using the tools of qualitative inquiry, in particular, thematic analysis, this study drew from the words of the teacher candidates as they participated in focus groups, as well as in their written reflections after participating in simulations during their coursework, to understand the role simulations may play in developing their capacity to enact core teaching practices through a justice-oriented lens.

Literature Review

This study was informed by three sets of literature that are rarely discussed together: justice-oriented teaching and learning, developing core teaching practices in practice-based teacher education, and the use of simulations in preparing teacher candidates to do the work of teaching. We drew on the literature to describe our approach to preparing justice-oriented teachers within practice-based teacher education and will explain here how we used the learning cycle to frame and inform our teaching. We situated our work within the growing body of simulation literature arguing how simulations provide an ideal (as well as underexamined) learning space for teacher candidates to develop skilled and just teaching practices.

Preparing Justice-Oriented Teachers in Practice-Based Teacher Education

A large body of research (e.g., Ball & Cohen, 1999; Grossman et al., 2009; McDonald et al., 2013) has asserted that professional learning should provide teacher candidates with the opportunity to inquire into the critical activities of the profession. Across our teacher preparation programs we center justice-oriented teaching and learning (Barton et al., 2020) within practice-based teacher education. As teacher candidates learn in and through practice (Ball & Cohen, 1999), our coursework is designed to intentionally interrogate our worldviews, assumptions, biases, and practices through dialog and intersectional action toward social change at the individual, school, and institutional levels.

Through this intentional work, our goal is to promote social transformations and alter participation and authority structures that are generally rooted in White supremacy and patriarchal dominance (Birmingham et al., 2017), which is the core of justice-oriented education. Yet, we acknowledge that this work is complex and messy; we are only in the beginning stage of this journey.

We imagine a teacher education space as a community of praxis (Schiera, 2021). This space seeks convergence between critical (e.g., Freire, 1970/2011) and social (e.g., Lave, 1991) learning theories (Schiera, 2021). Here, the fundamental critical orientations for teaching — student learning (understanding the difference between a test measure and learning), cultural competence (understanding diversity in asset-oriented ways), and developing sociopolitical/critical consciousness (a commitment and skills to act as agents of change) — are infused with culturally relevant and responsive practices (Ladson-Billings, 2021; Villegas & Lucas, 2002).

These practices include embracing constructivism, learning about students and their communities, and creating learning paths through various instructional activities that build on students’ interests and community resources (Villegas & Lucas, 2002). These critical orientations merge with fundamental social orientations for teaching: attending to situated learning in the context of practice through representations, decompositions, and approximations of practice (Ball & Cohen, 1999; Grossman, 2018; Schiera, 2021).

In our elementary mathematics and social studies methods classes we intentionally seek out a community of praxis as we create opportunities for learners to consider content, practice, and equity issues by scaffolding learning around core practices. We define core practices (e.g., explaining and modeling content; eliciting and interpreting student thinking; and leading a group discussion) as critical practices for students to learn content and skills (e.g., Grossman, 2018). By design, core practices are not intended to be standalone know-how, but they instead guide learners in navigating the complexities of the classroom since they are responsive to context (Kloser, 2014).

Yet, we realize a potential for core practices to peripheralize equity and justice, since these routines may oversimplify the complexity of teaching (Philip et al., 2018). Therefore, in communities of praxis, we leverage the ways core practices work toward justice-oriented practices with individual and collective impact on classroom culture (Barton et al., 2020).

For example, consider the practice of eliciting and interpreting student thinking. Eliciting and interpreting student thinking is always cultural and political (Schiera, 2021), in that it requires learners to tap into the conceptual tools that support them in seeing students from an asset-oriented perspective (Villegas & Lucas, 2002). Within an asset-oriented perspective, teacher candidates learn to recognize and value the linguistic, cultural, and socioeconomic diversity of students and consider how attending to core practices involve attending to culture, context, and justice (Schiera, 2021).

To bring core practices to life, teacher candidates’ engagement with these practices are carefully scaffolded so that they shift their lenses from being an observer of the work that teachers do (Lortie, 1975) to becoming a professional educator, gaining practical insight into the work that takes place in schools. We leverage the practice-based pedagogies of investigation to develop teacher candidates’ ability to analyze and critique justice-oriented teaching practices, while also positioning the pedagogies of enactment in ways that support them to do the practices of teaching within the context of coursework (Grossman et al., 2009; Kavanagh & Danielson, 2020; Kazemi et al., 2009).

Leveraging the Learning Cycle Framework

To scaffold learners’ attention to walking the talk, we use a learning cycle framework to guide our instructional decisions. Within the learning cycle framework, our goal is for learners to have opportunities to implement justice-oriented practices as they explore a unit of instruction, prepare and rehearse an activity to enact with students, enact the activity with students, and analyze the enactment (McDonald et al., 2013).

For example, as learners investigate the core practice of eliciting and interpreting student thinking, they first explore the practice while engaging with representations of practice such as direct observations of practitioners in the field, case studies, videos of classroom strategies, lesson plans, and PK-12 student work that provide them with opportunities to understand eliciting and interpreting student thinking in practice (Grossman et al., 2009).

Next, learners decompose eliciting and interpreting student thinking by breaking down the practice into its component parts as they prepare to enact the practice with students. As learners prepare to elicit and interpret student thinking within the context of their methods coursework, they formulate questions that probe student thinking, consider how to listen and notice specific features of student thinking, as well as learn how to focus on a strategic aspect of a student’s thinking to probe further. Also, in this phase of the learning cycle, learners’ approximate practice as they rehearse the activity.

Approximations of practice are opportunities for learners to enact core practices in ways that are proximal to the practice of teaching. These approximations of practice provide learners with scaffolded opportunities to develop their professional practice as they simulate aspects of core practices through activities such as role-plays (e.g., Schultz et al., 2019), microteaching (e.g., Zhang & Cheng, 2011), coached rehearsals (Kazemi et al., 2015), teaching minilessons or parts of lessons (Davis & Nelson, 2011), or simulations (Murphy et al., 2018). Although approximations of practice are not the real thing, they provide learners with opportunities to experiment with new skills, try on a new role, or develop a new way of thinking while receiving feedback from their instructor, mentor, or peers that support them to refine their instructional practice (Grossman et al., 2009).

During the next phases of the learning cycle, learners enact the activity with PK-12 students and then reflect on the enactment. These phases are a critical part of the learning cycle because it provides novices with the opportunity to improve teaching on a particular topic. As learners teach students, teacher educators (e.g., mentor teachers and university methods instructors) may engage in live, in-the-moment coaching or coteaching to provide in-the-moment modeling (McDonald et al., 2013).

Further, as learners teach, they capture their enactment in concrete ways, such as taking video of their efforts, to receive additional feedback from teacher educators and colleagues. These concrete artifacts of enactments are then used during the analysis phase of the learning cycle to unpack the teaching and learning that happened during the lesson. In sum, the literature illustrates that this final phase of the learning cycle provides learners with the opportunity to compare their initial and current understandings about teaching and learning.

Practice-based teacher education and, in particular, the learning cycle not only scaffold learners’ instruction within coursework but serves as a framework positioning the pedagogies of investigation and enactment that inform our work as teacher educators. Consequently, we wondered how to best support our students in preparing for and practicing justice-oriented core practices before enacting them in real classrooms with real students, especially since traditional role-plays, where learners present a lesson to a group of their peers, may not authentically represent a classroom environment and present little to no real-world consequences (Storey & Cox, 2015). Because of this wondering, we turned to simulations as a learning space to support novice learning.

Using Simulations to Support Teacher Candidate Learning

Since research indicates that simulations feel like a more authentic form of practice (Dalinger et al., 2020), there is a notable trend in infusing more authentic experiences, assisted by technology, into teacher education coursework. In this space, simulations are designed in ways that connect theory to practice through detailed scenarios intended to portray authentic classroom experiences. The intent of this practice space is to prepare learners for the realities of the classroom because they can practice specific skills, as often as needed, in a fully controlled environment (Brownell et al., 2019).

Here, real and virtual worlds are combined to give learners a sense of immersion with both physical and social presence (Biocca et al., 2003). This means that learners feel that they are in the classroom with the students and that they have a meaningful impact on their learning (Hayes et al., 2013). Hence, learners can practice what they are learning, reflect on it afterward, and practice the skill again (Kaufman & Ireland, 2016). This space may not only provide learners with the opportunity to hone core practices, develop content knowledge, and the pedagogical content knowledge that is needed for teaching, but also to foster the development of teaching dispositions (Kaufman & Ireland, 2016).

Because of the potential of this space for honing teaching practices, research on the use of simulations within the field of teacher education is growing across a range of experiences. Although this is not intended to be an exhaustive list of examples, research related to special education coursework is finding that simulations have been used to focus on developing learners’ skills to manage the learning environment (Hudson et al., 2019), implement Discrete Trial Teaching (Fraser et al., 2020), and to navigate multiple collaborative relationships in inclusive settings (Driver et al., 2018).

In science, technology, engineering, and mathematics coursework, simulations focus on facilitating whole class discussions in elementary mathematics and science (e.g., Lee et al., 2018), facilitating argumentation-focused science discussion (Mikeska & Howell, 2019), and leveraging number talks to elicit students’ mathematical thinking while developing professional noticing skills (Woods, 2021). Here, simulations not only provide learners with the opportunity to build their instructional skills, but to interact with students in a way that recognizes the relational work of teaching. Thus, learners share their vulnerabilities as they confront their concerns about not being able to respond to students’ mathematical thinking, while positioning students as sensemakers and noticing missed opportunities to support students’ mathematical reasoning.

Research also showcases how simulations provide learners with the opportunity to experiment and grow as they receive ongoing feedback (Landon-Hays et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021; Woods, 2021). For example, Lee et al. (2021) found that learners who rehearsed and were coached within simulations were less likely to position elementary students as passive participants than those who rehearsed in peer-to-peer settings. Also, they found that learners who participated in simulations, as compared to peer-to-peer rehearsals, may be more comfortable with the level of students’ responses and, therefore, did not revert to more literal types of questioning or repeating. Further, this opportunity to practice within simulations mitigates the risk to others (e.g., students in PK-12 schools and mentor teachers), since learners can learn to carry out core practices in a supervised or coached space before enacting it in the real-world with students (Kaufman & Ireland, 2016).

Yet, gaps remain in the literature about the role of simulations in field experiences (Hixon & So, 2009), the learning outcomes afforded by simulations (Billingsley & Scheuermann, 2014), and how to foreground justice-oriented core practices meaningfully into simulations. Since there is scant research where learners enact justice-oriented core practices during simulations, this study aimed to build a foundation for the development of such literature.

Research Methods

This qualitative study investigated how simulations supported the development of justice-oriented teaching practices among teacher candidates enrolled in our elementary mathematics methods and social studies courses. We turned to qualitative methods because we were interested in knowing how individual candidates were (or were not) taking up justice-oriented core practices during simulations that we designed for our classes.

Within qualitative methodology, thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) allows one to explore patterns and relationships across data sources (Fereday & Muri-Cochrane, 2006) in ways that are central to the description of the phenomenon (Daly et al., 1997). We hoped the themes originating from the words of our teacher candidates that emerged as most salient would help us understand the relationship between theory and practice. More practically, we hoped the study’s findings would inform and guide our use of simulations, as well as our approach to teaching justice-oriented teaching practices. To this end, the research question we explored in this study was as follows: What role did simulations play in developing candidates’ capacity to enact core teaching practices through a justice-oriented lens?

Participants and Setting

The university-based teacher preparation program used for this study was large and comprehensive, with five pathways to initial certification. The elementary undergraduate program featured in this study, however, is by far the largest with close to 600 students. Our university, located in a predominantly White, wealthy suburb in the midwestern US had a largely White student population, which contributes to our commitment as a faculty to the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Additionally, all three authors identify as White, cisgender females with a commitment to both practice-based teacher preparation and social justice. Dawn teaches the elementary mathematics methods course, Linda teaches the elementary social studies methods courses, while Cindy, as a neutral (noninstructional) observer, assisted by conducting focus groups with study participants after the term ended. All three authors contributed to data analysis.

Study participants, in addition to the two aforementioned faculty instructors, included 29 teacher candidates enrolled in mathematics methods and 32 teacher candidates enrolled in social studies methods. Data were collected during fall 2020, when we taught remotely due to the coronavirus pandemic. Of note, 18 of the 61 consenting candidates were enrolled in both methods courses at the same time. Having already completed all introductory and foundational coursework, these candidates were now one or two terms away from their student teaching semester. Additionally, a smaller group of 13 teacher candidates who had participated in simulations across a wider range of courses, elementary and secondary, shared their experiences in one of three focus groups conducted at the end of the semester. Collectively, from focus group to classroom, these mostly White female teacher candidates mirrored the diversity in our program, thus serving as a representative sample of students (see Table 1).

Table 1

Participants and Reflections

| Participants | Artifacts in Chronological Order | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematics Methods | 11 | Number Talk 1 [NT1] | Number Talk 2 [NT2] | Number Talk 3 [NT3] |

| Social Studies Methods | 14 | Historical Thinking 1 [HT1] | Historical Thinking 2 [HT2] | |

| Both Methods Courses | 18 | Number Talk 1 [NT1] Historical Thinking 1 [HT1] | Number Talk 2 [NT2] Historical Thinking 2 [HT2] | Number Talk 3 [NT3] |

| Focus Group Number | 13 | FG1 | FG2 | FG3 |

Data Generation

Three sets of data informed this study. First, we collected the written reflections of teacher candidates enrolled in each of Dawn’s and Linda’s methods classes. As will be explained, these reflections varied by instructor, with two to three reflections (ranging from one to three pages each) collected per consenting candidate (see Appendix A). Additionally, teacher candidates from all classes using simulations that term were invited to participate in one of three 30-minute focus groups. The purpose of the focus group interview, conducted after the term was over, was to gather candidate impressions of using simulations (Morgan, 2018; see Appendix B). Finally, instructor reflections on the semester informed the research.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using a recursive and reflective process common to thematic analysis. Starting with the focus group data, each author read and reread the transcripts, looking for salient themes central to the description of the phenomenon (Daly et al., 1997). During this process, three phrases emerged as both salient and generative: safety net, less messy, and enacting justice-oriented practices. Curious to know more, we deeply dove into the candidates’ written reflections, starting with mathematics, then following with social studies. To ensure the strength and validity of our findings in this second round of analysis, we worked as a team to iteratively read, code, and discuss the data (Saldaña, 2021).

At times, we followed individual students and, when possible, across courses. At other times, we looked holistically at the data for repeating themes across the subject areas. This process of data analysis took roughly 6 months to complete, as we were continually checking our work, employing credibility measures of triangulation and looking for disconfirming evidence (as recommended in Brantlinger et al., 2005). Ultimately, our aim was to understand what candidates meant when they described simulations as a safety net, less messy, and enacting justice-oriented practices, ideas that gained strength the more we examined the data (see Table 2 for definitions of themes and representative examples from the data). Before turning to the findings, we describe our use of simulations and the teaching scenarios that informed this study.

Table 2

Themes and Representative Examples

| Theme | Definition | Representative Example from Data |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Net | Simulations are a safety net, or a safe space, to develop core practices without negatively impacting individuals in PK-6 classrooms. | These Mursion simulations gave me good practice in teaching mathematics at a stress-free level. Had I been doing this with real students I would have felt more pressure and wouldn’t want to mess up. By doing this with simulation students and receiving a video of my teaching, I was able to learn a lot about myself as a teacher and reflect on how to improve for when I am teaching real kids. This helped me to avoid all the mistakes I would have made when first starting out in the classroom because now I know what I need to be aware of without harming real kids (Lucy, NT3). |

| Less Messy | Simulations are a less messy, or controlled space, where PSTs learn to engage in the practice of teaching. In this space, PSTs get to know the same students, receive coaching, and rehearse the justice-oriented core practice again. | After Number Talk 1 reflection, I learned to rephrase students’ ideas and to use wait time extensively as the students shared their inputs, and these talk moves led me to honor their contributions in Number Talk 2. Additionally, I learned to utilize the remaining talk moves appropriately during the Number Talk 3 because of the Number Talk 2 reflection. These simulations and reflections were greatly beneficial in my education experience this semester because I gained more confidence in leading number talks and eliciting students’ thinking and strategies (Nu, NT3). |

| Enacting Justice-Oriented Practices | Simulations are a learning spaceto enact justice-oriented practices. In mathematics the focus may be on equitable and just teaching practices (e.g., considering how to support students to share their thinking via multiple approaches to solving problems; drawing on students’ lived experiences and interests) and being intentional to build on the assets that each learning brings to the classroom. In social studies this may be how content is presented to students and the opportunities they have to historically investigate systemic inequalities. | Mathematics: I no longer feel like I have to be an encyclopedia of information. I now understand that my students hold so much information and have so much to share (Lucy, NT3). Social Studies: I am interested in how to broach those contentious opinions students bring up. For example, would it make sense to say ‘do you guys think the Pilgrims appreciated or thought the Indigenous People were less than them?’ if they made them sit on the ground, in response to Jayla pointing out it was rude that the Indigenous People were sitting on the ground while the Pilgrims were at a table (Jenny, HT1)? |

Our Use of Simulations

In our program we use an innovative mixed reality simulation software available from Mursion® (developed as TLE TeachLivE™) to facilitate rehearsals. These simulations allow teacher candidates to practice interactions with students. Typically, the simulated classroom environment was projected onto a large computer or screen, and interactions were facilitated through a web camera in a fishbowl setting. Because of the global COVID-19 pandemic, we transitioned to small group (e.g., four to six teacher candidates) fishbowl discussion via the Zoom® videoconferencing platform.

During our simulations, teacher candidates interacted with five fifth-grade students in an upper elementary classroom. These students — Mina, Will, Jayla, Emily, and Carlos — were aged between 9 and 10 years old and intentionally designed to be ambiguous in relation to demographics. A trained simulation specialist controlled the scenarios (or builds) developed by the instructors to guide each rehearsal. These scenarios were not scripted, but followed an instructional activity (e.g., number talks) guided by how students may respond to the questions posed by the teacher candidate. The following section describes the scenarios created for the Number Talk Project and Historical Thinking scenarios.

The Number Talk Project in Elementary Mathematics

In our mathematics coursework, we recognize justice-oriented teaching practices as core practices (e.g., eliciting and interpreting student thinking) that restructure power relationships in classrooms and the ways they intersect with historicized injustice within local contexts (Barton et al., 2020). Although we are at the beginning stage of this journey, the goal is to change the game of mathematics (Gutiérrez, 2018) by addressing students’ identities as doers of mathematics (Aguirre et al., 2013; National Research Council [NRC], 2001). Hence, our coursework is designed so that teacher candidates develop content and pedagogical content knowledge for teaching mathematics (e.g., Ball et al., 2008) and connect that understanding to their own privileges (Goffney, 2016) and to the students they serve in local classrooms (e.g., Aguirre et al., 2013; Gutiérrez, 2018).

The Number Talk Project (Woods, 2021) serves as an entry point into changing the game of mathematics. Number talks are short, 10- to 15-minute mathematical discussions where students solve problems and share how they made sense of the problem (e.g., Parrish, 2010/2014). The design of the number talk routine lends a structure that guides teacher candidates to elicit students mathematical thinking as they learn to (a) launch the number talk, (b) provide time to make sense of the computation problem, (c) gather answers to the problem, (d) facilitate a discussion about solution strategies and connections between the strategies, and (e) summarize key ideas. Particularly salient is the way eliciting and interpreting students’ mathematical thinking, when embedded in the number talk routine, guides teacher candidates to enact the justice-oriented practice of assessing, activating, and building on prior knowledge (Seda & Brown, 2021) as they notice students’ mathematical thinking (Woods, 2021).

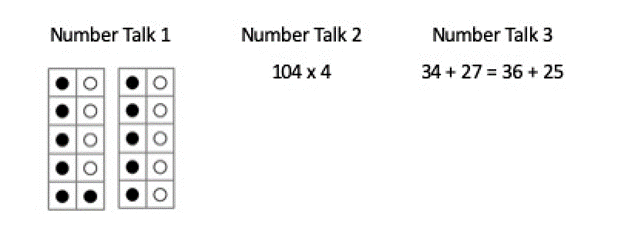

During this project, small groups of three to six teacher candidates rehearsed three 8-minute number talks at Weeks 4, 9 and 13 of the 14-week semester with their instructor present (see Figure 1). The main goals of each simulation were to (a) elicit thinking by posing general, open-ended questions, (b) listen for ideas without interrupting students, (c) develop additional questions to unpack what a student says, and (d) refrain from directly teaching a method to solve the problem.

Figure 1

Number Talks Across the Semester

Before each simulation, teacher candidates investigated number talks by participating as a student, examined video exemplars, and planned the number talk with a small group of peers. During the simulation, teacher candidates observed their colleagues to continue the investigation of what it means to elicit and interpret student thinking. After each simulation, teacher candidates debriefed with the instructor, viewed the video of their number talk, and wrote reflections about their rehearsals.

Historical Thinking in Elementary Social Studies

A core focus of social studies coursework is to wrestle with the complexities of a complex, diverse world. In doing so, educators discern and disrupt their assumptions of the world and develop ways to enact justice-oriented teaching practices. Doing the work of justice related explicitly to history education requires cultivating critical consciousness of social injustices of the past to promote freedom in the present. However, the teaching and learning of disciplinary literacies in justice-oriented social studies is inherently messy and does not come naturally to students (Martell & Stevens, 2021; Monte-Sano & Cohran, 2009; Shreiner, 2018). Therefore, if social studies, in theory, is justice-oriented, then theory and practice must work in tandem to guide instructional practices in the classroom.

In the following simulations, the instructional goal was to put justice-oriented theory into practice. Specifically, teacher candidates were expected to encourage the students’ critical interpretation of the past to disrupt the status quo narratives represented in the images. To do so they engaged students in critical historical thinking using primary sources during two 10-minute simulations, each completed outside of class and without the instructor present.

The simulations’ goals were to analyze an image of the Signing of the Constitution (Cristy, 1950) and the First Thanksgiving (Ferris, 1932) using the historical thinking skills of sourcing, contextualizing, corroboration, and close reading (see Figure 2). Within this critical frame, they elicited and interpreted the students’ ways of thinking, sought to challenge false assumptions, and in honoring them as constructors of knowledge, led them to new ideas and ways of thinking.

Figure 2

Historical Thinking Images

Image B: Library of Congress http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3g04961/

To prepare teacher candidates for the simulations in the exploration phase, we modeled historical thinking skills with intentional attention drawn to each skill and each teachable part of eliciting and interpreting their thinking. Additionally, classroom videos offered further examinations of what those teachable parts — formulating and posing questions, listening to students’ responses, and developing probing questions — might look like in social studies. Then we worked on building content knowledge, formulating questions, anticipating how students might respond, and wrote follow-up questions. Following each simulation, teacher candidates viewed their videos, wrote reflections of their enactments, and received instructor feedback.

Findings

As we analyzed the focus group transcripts, three themes regarding the role of simulations as a tool for promoting justice-centered teaching emerged from the words of the teacher candidates: (a) simulations provided a safety net to iteratively practice justice-oriented interactions, (b) simulations made practice less messy, and (c) simulations offered a safe space to talk through tough issues.

To understand the strength and nuances of each theme, we turned to the teacher candidates’ written reflections, completed at the end of each simulation cycle across the two courses to find evidence of these themes in their individual reflections. Using instructor notes and reflections as an additional guide, examples in this section illustrate the ways in which our data supported each theme, detailing how simulations were leveraged to advance teacher candidate learning of justice-oriented teaching practices. For each of the three themes we provide an overview emerging from the focus group data and then illustrate the theme using data with salient examples from coursework reflections.

A Safety Net to Iteratively Practice Justice-Oriented Interactions

…One of my favorite things about Mursion [simulations] is that it gave me the ability to practice in kind of a safe environment and that safety net was you could practice, without it negatively affecting…any real people because it was like practicing on avatars. (Sadie, Focus Group [FG] 2)

Teacher candidates in the focus groups (after the completion of coursework), as well as in their written reflections (during coursework), noted how simulations provided a safety net during practice. As teacher candidates rehearsed instructional activities within the simulations, they realized the importance of preparation, especially when learning to build instruction upon their students’ ideas. Thus, many teacher candidates felt that the simulated environment provided a safety net where they could be at ease in an instructional setting that supported the “opportunity to practice and build confidence” without causing harm to students’ identities (Callie, FG3). Teacher candidates also appreciated continued practice (and coaching), since this was one of the few opportunities to be the teacher of record. This autonomy provided an invaluable opportunity to bring a core practice to life as teacher candidates learned how to walk the talk.

A Safety Net Example During Number Talks

After the first number talk rehearsal, many teacher candidates like Brandon reflected, “how underprepared I am for both teaching mathematics and number talks in general.” He continued to write, “I used vague language that sort of ruined the execution of my plan and wasted time.” Other students, like Anna, noted how simulations gave them “the opportunity to work with students and fine tune my teaching skills without having the fear of messing up and hurting a students’ education” (NT1). Hence, simulations became a safety net to understand what it means to walk the talk regarding changing the game of mathematics without impacting PK-6 students’ identities.

Over time, teacher candidates began to note improvement in their teaching skills. For example, during Number Talk 3, Maria decided to engage students by using a real-world context, in part to keep Will from falling asleep. She reflected, “They needed to solve the problem to figure out if it was true or false that the two skateboarders [Tony Hawks and Rodney Mullen] tied in the competition. Will did not fall asleep this time and he was engaged!” Other students also noted growth during their third number talk reflection. For example, Julian said,

I felt discouraged after the first [number talk] … but I think they are helping me grow tremendously and giving me so many things to keep working on. I feel as though they have already helped me feel a bit more comfortable to be able to do them with real students in the classroom, or even a virtual setting (NT3).

Moments like this highlight how simulations protected the identities of PK-6 students, while teacher candidates were afforded with the opportunity to hone ways to elicit and interpret student thinking. As they participated in iterative, coached practice (via cycles of investigation and enactment), teacher candidates reported feeling more comfortable in having mathematical discussions with students. Most teacher candidates were grateful for the simulation since, “the experience was helpful and gave me practice in a real way” (Julian, NT1), and “I can rest easy as this feels far more ethical” (Brandon, NT1).

Learning Justice-Oriented Core Practices Were Less Messy

I think I would have learned it in person, but in a different, maybe drawn out, messy way. (Laurie, FG1)

As teacher candidates considered how the simulations prepared them to walk the talk, they discussed how the various practice opportunities allowed them to “have that test and fail, and then [time to] refine, and then learn from it” kind of opportunity (Joey, FG1). In this space, teacher candidates discussed how these experiences supported them to develop intentional language (e.g., to elicit student thinking or to pose purposeful questions) in ways that supported diverse learners. Salient to this point, teacher candidates felt that simulations provided a less messy way to learn, because they were coached through the experience by their instructors. Instructors offered guidance and feedback about justice-oriented core practices within the context of academic content. Also, there was also the opportunity to apply the feedback in a future simulation. Teacher candidates felt that this intentional practice was different from many of their prior experiences within field placements, since they rarely had the opportunity to work on specific aspects of practice while observing or working with small groups of students.

Less Messy Number Talks

Since student-centered teaching is highly contingent, often unpredictable, and requires teachers to notice and interpret student thinking, number talk simulations became a less messy space in which to learn how to manage these in-the-moment decisions. As teacher candidates progressed through the three different number talk experiences, simulations provided a less messy space for teacher candidates to elicit and interpret student thinking in ways that advanced justice. When teacher candidates learned how to uncover and support students’ thinking, they began to position them as capable doers of mathematics. For example, Brandon revealed in his third number talk reflection,

I figured equity fell under differentiation, but now I see it is more than that. With something as simple as allowing students to share methods, or even just answer in their own ways we give students a greater opportunity to learn not only from successes, but from mistakes as well. Communication is at the heart of this; dialog opens a world of possibilities for our students. I have learned quite a bit in our number talks about the effectiveness of student dialogue. It is the difference between teaching and learning.

In this moment, Brandon realized a critical step to change the game of mathematics: supporting students in doing and talking about mathematics. Although he did not explicitly reference how students should have the opportunity to draw from their cultural and linguistic resources, Brandon did address building students’ identities as doers of mathematics, since sharing methods and learning from successes and mistakes supports the development of a productive disposition.

Less Messy Simulations in Social Studies Methods

Our findings show that the simulations provided a protected less messy space in which to practice eliciting and interpreting students’ critical historical thinking to advance justice. As an instructional tool, historical thinking allowed learners to elicit and interpret students’ historical thinking as a way of interpreting (theory) and doing (practice) the work of justice in the classroom. We infused the practice of historical thinking within the critical frame of engaging students in seeing the world differently.

Teacher candidates’ written reflections and focus group comments consistently revealed their appreciation of practicing in an environment where they had time to prepare, enact, and reflect on their work. This less messy scaffolded and instructor supported practice allowed teacher candidates to learn about the practice, about students as learners, and about themselves as facilitators. Brandon’s (HT2) comment captures these thoughts well:

I feel like I have mentally prepared myself to do 90% of the talking, and now there is a better method that only requires me to do about 20% of it instead. I love conversations about social studies, and it is hard to stand by and not contribute too much to the conversation. This is going to for sure have to be something that I work on. Another thing I know I need to work on is how to probe in the right direction. I hate to say that, but I feel like it is something that has to happen eventually. We want kids to come to their own conclusions, but I feel like every once in a while, this could go wrong.

Additionally, most teacher candidates appreciated the chance to try again in the second simulation. Stella’s (HT1) comment summarizes well what so many others expressed:

In general, I was disappointed with my ability to probe and unpack students’ thinking. The main reason behind this, in this case, was that I felt very rushed and as though I needed to move forward. I was also trying to avoid lecturing or giving excessive additional information and was unsure how much context students have. I look forward to giving students the chance to go deeper in their thinking during the next simulation.

However, while appreciating the simulations as a place to practice, some candidates also expressed concern. In a focus group interview, Gabriella speculated,

I think it’s still trial and error, and while it may be messier to teach in person, I feel like it might be a little more rewarding. If you were to take this into the classroom, you might actually learn a bit more, or you know, it might be messier, but it might be more rewarding in the end.

Expanding the Less Messy Space

Overall, teacher candidates embraced the simulations as meaningful ways to practice teaching, but they also yearned to enact what they were learning in coursework with students in our partner schools, thereby rounding out the learning cycle framework. Salient to this point is that, as the semester progressed, some teacher candidates had the opportunity to continue learning as they enacted the instructional routines they had rehearsed in the simulations with students in their online field placements. Joey, during FG1 said,

I did pretty much the same thing twice [in simulation]. I was able to refine it a lot better and realize what kind of questions worked and what didn’t. And then the very next day after my second Mursion [simulation], I actually had my actual in-class virtual whole group discussion, and it went much better than I could ever have expected, thanks to what I was kind of learning from Mursion [simulations]. It went very similarly to how [my] Mursion [simulation] went, I think, and I felt like it really prepared me for that.

Further, other teacher candidates related simulations to virtually teaching students through the Zoom platform. This was an unexpected outcome, especially in the sense that the simulations supported learners to transfer what they were learning in coursework to their virtual field placements. Students often reported feeling more confident in their Zoom field placements because of their work in simulations.

These stories led us to wonder whether and how simulations could be used as a less messy space throughout our teacher preparation program. Relatedly, teacher candidates within focus groups also wondered about the kinds of skills that they could have developed if they had experienced simulations earlier in the program. Would they have had a greater opportunity to grow, learn, and transfer core practices to their work with students in their field placements?

Potential for Less Messy Simulations to Feel Inauthentic

Although experiences within simulations were overall positive, it is important to note there was a fine line between less messy and inauthentic. Simulations have the potential to feel constructed or exaggerated because the students may not behave as expected; conversations may feel unnatural because of intentional talk moves and questions; and limitations of the simulated classroom build hinder the ability to hand out materials, perform physical functions such as a thumbs up, or remembering previous instruction.

Additionally, limitations of the build may provide teacher candidates space to consider only surface features of social justice practice/praxis, especially since avatars were designed with ambiguous demographic characteristics. Yet, through these simulations, we found teacher candidates walking the talk as they investigated ways to support student thinking through a justice-oriented lens.

Safe Space to Talk Through Tough Issues

So, I thought it was a nice way to have a safe space to try and talk about tough issues that might include social justice and topics like racism and things of that nature and history, to better prepare us for real conversations with students. (Eva, FG 2)

Building on the previous themes of safety net and less messy, teacher candidates also spoke of how simulations became a learning space to enact justice-oriented practices when attending to practice and content. In this data, justice-oriented practices included handling off-task behavior in respectful ways, supporting students who may have been marginalized or positioned as unable to engage with content, or speaking to students about race and racism. Because these practices are present in schools, intentional conversations and targeted feedback about them are needed. In this regard, simulations provided a learning space for teacher candidates to navigate the complexities of teaching for equity and justice while attending to specific content in mathematics and social studies.

A Safe Space Example During Historical Thinking Simulations

Recall that our social studies core focus was to wrestle with the complexities of a complex world, and in doing so, discern assumptions, disrupt inequalities, and develop new modes of teaching and learning. Martell and Stevens (2021) argued that teaching history for justice must begin in teacher preparation programs. Teacher candidates need guided support, opportunities to practice, access to resources, and time for self-reflection. The two simulations, scaffolded and supported, provided a safe space to struggle with this new teaching mode.

Using an inquiry-based, student-centered approach, teacher candidates led students in considering alternative interpretations of history. This type of learning requires questioning biases and pushing against dominant ways of knowing. Teacher candidates struggled with leading students to question who was not in the room to sign the Constitution or why on the First Thanksgiving, Indigenous people sitting on the ground insinuated they were less wealthy than the European settlers. Questioning perspectives and biases is difficult work.

Written reflections reflected these struggles:

- “How will I ever teach like this when other teachers don’t?” (Morgan, HT2)

- “I have never analyzed images and don’t know what I’m doing, so how can I do this with real students?” (Leah, HT1)

- “I am in a school that is reluctant to introduce mistruths or misconceptions. I need growth in this area, so I know how to handle this.” (Alicia, HT2)

Hence, the simulations were a safe space to practice, yet simultaneously exposed the messy work of seeing and thinking regarding eliciting and interpreting students’ historical thinking through a justice-oriented lens.

Discussion and Implications for Practice

Although our adoption of simulations took place during the global coronavirus pandemic, we found that they not only augmented our White teacher candidates’ field experiences but also gave us a window into the ways they took up and rehearsed the justice-oriented core practice of eliciting and interpreting students’ thinking. We noticed that simulations provided an authentic approximation of practice in a controlled environment (a.k.a. safety net) that protected PK-12 students’ developing dispositions for mathematics (Philipp & Siegfried, 2015) and social studies (National Council for the Social Studies, 2017).

Building on this, we found that as teacher candidates engaged with coursework, scaffolded by the learning cycle framework, they were immersed in a less messy space (as compared to the messy realities of PK-12 classrooms) to rehearse eliciting and interpreting student thinking in ways that valued students’ ideas (McDonald et al., 2013). This less messy space supported teacher candidates to elicit and interpret students’ thinking in ways that honored the relational work of teaching (Woods, 2021) as they participated in activities intentionally crafted to support the development of their critical consciousness.

Further, this less messy space provided a unique opportunity to practice (and be coached), reflect, and practice (again) difficult and challenging issues that may occur when enacting eliciting and interpreting student thinking in asset-oriented ways within mathematics and social studies content (Dieker et al., 2014; Kaufman & Ireland, 2016; Lee et al., 2021). Although this qualitative study was small, it serves as an important step toward filling a gap in the literature about the role that simulations played when connected to or used as a substitute for field experiences.

Simulations supported teacher candidates to interrogate their practice, because simulations when coupled with the learning cycle framework (McDonald et al., 2013) became a safe space to talk about tough issues. Through carefully crafted instructional tasks and follow-up coaching, we found that simulations played a valuable role in providing teacher candidates with focused and sustained opportunities to hone their skills and approximate justice-oriented practice (Grossman et al., 2009).

We realize that the terms safe space (or safety net or less messy) that the teacher candidates used to describe their experiences may be perceived as problematic when viewed through a critical lens. Therefore, we intentionally leveraged the messy and uncomfortable moments within the simulation to support teacher candidates in interrogating their practices and their beliefs as they recognized and learned to value the linguistic, cultural, and socioeconomic diversity of students as they learned to let go and listen (Schiera, 2021; Villegas & Lucas, 2002). Yet, we realize that we are only just beginning to understand how to support the development of culturally responsive practices (Villegas & Lucas, 2002).

We were fully aware that being in a less authentic, less messy environment than traditional classrooms had limitations. Limitations of the build, such as avatars being intentionally designed with ambiguous characteristics, have the potential to draw teacher candidates’ attention to technicalities of what works, rather than to the complexities of linguistic, cultural, and socioeconomic diversity of students (Grossman, 2005). Additionally, we acknowledge that participating in simulations does not fully immerse teacher candidates in the classroom’s murky, complex realities (such as learning how to coconstruct learning communities with students to manage daily interactions).

Further, as we draw learners’ attention to noticing, naming, and enacting core practices to promote social transformation, we must also find ways to address larger structural inequalities of race, gender and sexuality, and language (Dutro & Cartun, 2016) and how to support teacher candidates to be change agents as they develop content and pedagogical content knowledge (e.g., Ball et al., 2008) while connecting understandings to their own privileges (Goffney, 2016) and to the students they serve in local classrooms (e.g., Aguirre et al., 2013; Gutiérrez, 2018).

As we continued to imagine and reimagine our teacher education space as a community of praxis, we recognized the possibility for tension between practice-based approaches and simulations. For example, we wondered if supporting our teacher candidates to learn core practices (situated within the learning cycle framework) during simulations in university classrooms developed the skills that they should be capable of before assuming responsibility for a classroom (Forzani, 2014) and if those practices aligned with the skills our PK-12 partners prioritized within the context of their schools.

We also noted a tension, or need, for teacher candidates to have multiple opportunities to develop personally and professionally in justice-oriented work that extend beyond the university, so that they can be immersed in the complex and messy realities of PK-12 schools. These opportunities are needed so that teacher candidates can develop individual visions of justice-oriented schooling as they have (scaffolded) time and space to see, understand, and disrupt inequitable disparities between social groups (Shiera, 2021). Therefore, continued collaborative work with our partners is needed to define (and enact) justice-oriented practices to ensure that what teacher candidates are learning in the university methods classes supports and enhances similar work in the classroom.

Opportunities are also needed to further develop simulation experiences that truly reflect the complexities of justice-oriented schooling. For example, avatars need to be designed to authentically portray people of color and the strengths they bring to classroom communities. Moreover, further research is needed to determine if simulations ultimately produce teacher candidates who are justice-oriented when they are interns, as well as teachers of record.

As we continue to prepare justice-oriented teachers via simulations, three essential questions propel us forward. First, how might we use these findings to better align the key components of our teacher education curriculum (e.g., social foundations, teaching methods, and field experiences in partnership schools) with our vision of justice-oriented teaching practices? In practical terms, are candidates taking up these practices in the ways we hope, and are those practices becoming increasingly sophisticated over time? Our findings suggest we have found a generative line of inquiry; thus, we look forward to sharing our results with program faculty and exploring the possibility of replicating or modifying our research design in other courses (i.e., foundations and methods) and in other settings (i.e., campus and field) for the purpose of continuous improvement.

Second, we wonder how else we might use simulations to engage ourselves, teacher candidates, and various stakeholders as a community of praxis. We wonder how we can continue conversations around critical frames that permeate our vision for teaching and its pedagogical and programmatic implications (McDonald et al., 2013). At the present time, we use simulations early in the program to help candidates learn to look at teaching in new ways. As candidates enter major standing, we use simulations in select methods classes to coach candidates in the skillful use of core teaching practices. This study highlights an additional aim: supporting candidates in justice-oriented core teaching practices. Because we use simulations in different ways, for different purposes, at different times in the program, we have unique opportunities to continue studying the affordances and constraints of using simulations as a tool in helping candidates learn to teach in equitable and just ways.

Our final question is perhaps the most important: How do we ensure that in the less messy simulated experience, we continue to engage teacher candidates in the messy, complex work of advancing justice in the classroom? Our findings highlight the value of providing candidates with opportunities to try on and practice this kind of teaching in a safe and controlled setting, as the work of teaching from a critical consciousness lens is clearly difficult. Future research will need to explore the relationship between learning to teach in a simulated environment and engaging in authentic practice with real children, in real schools to determine if the work of teaching for justice translates from simulation to the classroom.

Although more and different types of data are needed to confirm whether and how the lessons learned in simulations support teacher candidates in enacting justice-oriented core practices within field work, internships, or during their induction years, the evidence provided in this study illustrates that simulations have potential to build teacher candidates’ capacity to be transformative educators. Succinctly put, simulations provided a unique opportunity — a shared experience — for both the learner and for us, as teacher educators, to understand what it means to learn in and from practice. Simulations provided a lens into justice-oriented teaching practices and provided insight into how to best support our students in preparing for and practicing justice-oriented core practices before enacting them with students in classrooms.

Further, simulations provided learners with critical opportunities to continue practicing their teaching skills in a safe and protected setting. This work represents our walking the talk as we begin to fill the literature gap about the role of simulations in justice-oriented core practices work across academic disciplines. We look forward to working alongside others taking up this critical work of conceptualizing teacher education as communities of praxis that seek to understand and do the work of justice.

Author Note:

The manuscript is based on data from a study situated within the School of Education and Human Resources at Oakland University. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors, but we received in-house funding from our Technology Advisory Committee to establish our mixed reality simulation laboratory.

References

Aguirre, J., Mayfield-Ingram, K & Martin, D. (2013). The impact of identity in K-8 mathematics. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Ball, D., Thames, M., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching what makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108324554

Ball, D. L., & Cohen, D. K. (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In L. Darling-Hammond & G. Sykes (Eds.), Teaching as the learning profession: Handbook of policy and practice (pp. 3–32). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Barton, A. C. Tan, E., & Birmingham D. J. (2020). Rethinking high-leverage practices in justice-oriented ways. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(4), 477-494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119900209

Billingsley, G. M., & Scheuermann, B. K. (2014). Using virtual technology to enhance field experiences for pre-service special education teachers. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37(3), 255–272. ttps://doi.org/10.1177/0888406414530413

Biocca, F., Harms, C., & Burgoon, J. K., (2003). Toward a more robust theory and measure of social presence: Review and suggested criteria. PRESENCE: Virtual and Augmented Reality, 12(5), 456-480.

Birmingham, D., Calabrese Barton, A., McDaniel, A., Jones, J., Turner, C., & Rogers, A (2017). ‘But the science we do here matters’: Youth-authored cases of consequential learning. Science Education, 101(5), 818–844. http://doi:10.1002/sce.21293.

Brantlinger, E., Jimenez, R., Klingner, J., Pugach, M. Richardson, V. (2007). Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 195–207.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

Brownell, M. T., Benedict, A. E., Leko, M. M., Peyton, D., Pua, D., & Richards-Tutor, C. (2019). A continuum of pedagogies for preparing teachers to use high-leverage practices. Remedial and Special Education, 40(6), 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518824990

Christy I, & Howard, C. (1940). Signing of the constitution [Painting]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/item/2019685250/

Dalinger, T., Thomas, K. B., Stansberry, S., & Xiu, Y. (2020). A mixed reality simulation offers strategic practice for pre-service teachers. Computers and Education, 144, 103696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103696

Daly, J., Kellehear, A., & Gliksman, M. (1997). The public health researcher: A methodological approach. Oxford University Press.

Davis, E. A., & Nelson, M. (2011, April). Using approximations of practice in elementary science teacher education [Paper presentation]. Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Dieker, L. A., Rodriguez, J. A., Lignugaris/Kraft, B., Hynes, M. C., & Hughes, C. E. (2014). The potential of simulated environments in teacher education. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413512683

Driver M., K., Zimmer, K. E., & Murphy, K. M. (2018). Using mixed reality simulations to prepare preservice special educators for collaboration in inclusive settings. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 26(1), 57-77. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/181153/.

Dutro, E., & Cartun, A. (2016). Cut to the core practices: Toward visceral disruptions of binaries in practice-based teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 119-128. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.001

Fereday, J., & Muri-Cochrane, E. M. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80-92.

Ferris, J.L.G. (1932). The first Thanksgiving 1621 [Print]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2001699850/

Forzani, F. M. (2014). Understanding “core practices” and “practice-based” teacher education: Learning from the past. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 357–368.

Fraser D. W., Marder, T. J., deBettencourt, L. U., Myers, L. A., Kalymon, K. M., & Harrell, R. M. (2020). Using mixed-reality environment to train special educators working with students with autism spectrum disorder to implement discrete trial teaching. Focus on Autism and Other Development Disabilities 35(1), 3-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357619844696

Freire, P. (1970/2011). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc.

Goffney, I. D. (2010). Identifying, measuring, and defining equitable mathematics instruction. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Grossman, P. (2005). Research on pedagogical approaches in teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Review of research in teacher education (pp. 425-476). American Educational Research Association.

Grossman, P. (2018). Teaching core practices in teacher education. Harvard Education Press.

Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., & Williamson, P. W. (2009). Teaching practice: A cross-professional perspective. Teachers College Record, 111(9), 2055–2100.

Gutiérrez, R. (2018). The need to rehumanize mathematics. In I. Goffney, R. Gutiérrez, & M. Boston (Eds.), Rehumanizing mathematics for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students (pp. 1-10). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Hayes, A. T., Hardin, S. E., & Hughes, C. E. (2013). Perceived presence’s role on learning outcomes in a mixed reality classroom of simulated students. In R. Shumaker (Ed.), Virtual, augmented and mixed reality. systems and applications. VAMR 2013. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 8022, pp. 142-151). Springer.

Hixon, E., & So, H. (2009). Technology’s role in field experiences for preservice teacher training. International Forum of Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 294–304. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/74980/.

Hudson M. E., Voytecki, K. S., & Owens, T. L. (2019). Preservice teacher experiences implementing classroom management practices through mixed-reality simulations. Rural Special Education Quarterly, (38)2, 79-94. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870519841421

Kaufman, D., & Ireland, A. (2016). Enhancing teacher education with simulations. TechTrends, 60(3), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0049-0

Kavanagh, S. S., & Danielson, K. A. (2020). Practicing justice, justifying practice: Toward critical practice teacher education. American Educational Research Journal, 57(1), 69–105. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831219848691

Kazemi, E., Franke, M., & Lampert, M. (2009). Developing pedagogies in teacher education to support novice teachers’ ability to enact ambitious instruction. In K. Murphy, J. Cash, & J. Kellinger (Eds.), Crossing Divides: Proceedings of the 32nd annual conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia (Vol. 1, pp. 12–30).

Kazemi, E., Ghousseini, H., Cunard, A., & Turrou, A. C. (2015). Getting inside rehearsals: Insights from teacher educators to support work on complex practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487115615191

Kloser, M. (2014). Identifying a core set of teaching practices: A delphi expert panel. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(9), 1185–1217. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21171

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Asking a different question. Teachers College Press.

Landon-Hays, M., Peterson-Ahmad, M. B., & Frazier, A. D. (2020). Learning to teach: How a simulated learning environment can connect theory to practice in general and special education educator preparation programs. Education Sciences, 10(7), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070184

Lave, J. (1991). Situating learning in communities of practice. In L.B. Resnick, J.M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 63–82). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10096-003

Lee, C. (2008). The centrality of culture to the scientific study of learning and development. Educational Researcher, 37(5), 267-279. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08322683

Lee, C. W., Lee, T. D., Castles, R., Dickerson, D., Fales, H., & Wilson, C. M. (2018). Implementation of immersive classroom simulation activities in a mathematics methods course and a life and environmental science course. Journal of Interdisciplinary Teacher Leadership, 3(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.46767/kfp.2016-0020

Lee, C., Lee, T., Dickerson, D., Castles, R., & Vos, P. (2021). Comparison of peer-to-peer and virtual simulation rehearsals in eliciting student thinking through number talks. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 21(2), 294–324. https://citejournal.org/volume-21/issue-2-21/mathematics/comparison-of-peer-to-peer-and-virtual-simulation-rehearsals-in-eliciting-student-thinking-through-number-talks

Lortie, D. C. (1975). Schoolteacher. The University of Chicago Press.

Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational reform. Beacon Press.

Martell, C. C., & Stevens, K. M. (2021). Teaching history for justice: Centering activism in students’ study of the past. In W. Journell (Ed.), Research and Practice in Social Studies Series. Teachers College Press.

McDonald, M., Kazemi, E., & Kavanagh, S. S. (2013). Core practices and pedagogies of teacher education: A call for a common language and collective activity. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(5), 378–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248711349380

Mikeska, J. N., & Howell, H. (2020). Simulations as practice-based spaces to support elementary teachers in learning how to facilitate argumentation-focused science discussions. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(9), 1356–1399. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.2165

Monto-Sano, C., & Cohran, M. (2009) Attention to learners, subject, or teaching: What takes precedence as preservice candidates learn to teach historical thinking and reading. Theory and Research in Social Education 37(1),101-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2009.10473389

Moore, A. E. (2021). “My job is to unsettle folks”: Perspectives on a praxis toward racial justice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103336

Morgan, D. L. (2018). Basic and advanced focus groups. Sage Publishing.

Murphy, K. M., Cash, J., Kellinger, J. J. (2017). Learning with avatars: Exploring mixed reality simulations for next-generation teaching and learning. In J. Keengwe (Ed.), Handbook of research on pedagogical models for next-generation teaching and learning (pp. 1–20). IGI Global.

National Council for the Social Studies. (2017). Powerful, purposeful pedagogy in elementary school social studies [Position statement]. https://www.socialstudies.org/position-statements/powerful-purposeful-pedagogy-elementary-school-social-studies

National Research Council. (2001). Adding it up: Helping children learn mathematics. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9822

Parrish, S. (2010/2014). Number talks: Helping children build mental math and computation strategies. Math Solutions.

Philipp, R. A., & Siegfried, J. M. (2015). Studying productive disposition: The early development of a construct. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 18, 489-499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-015-9317-8

Philip, T. M., Souto-Manning, M., Anderson, L., Horn, I., J. Carter Andrews, D., Stillman, J., & Varghese, M. (2018). Making justice peripheral by constructing practice as “core”: How the increasing prominence of core practices challenges teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487118798324

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage Publishing. Schiera, A. J. (2021). Seeking convergence and surfacing tensions between social justice and core practices: Re-presenting teacher education as a community of praxis. In Journal of Teacher Education, 72(4), 462–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487120964959

Schultz, K. M., Danielson, K. A., & Cohen, J. (2019). Approximations in English language arts: Scaffolding a shared teaching practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 100-111.

Seda P., & Brown, K. (2021). Choosing to see: A framework for equity in the math classroom. Dave Burgess Consulting, Inc.

Shreiner, T. L. (2018). Preparing social studies teacher for challenges and opportunities of disciplinary literacy in a changing world. In C. C. Marshall (Ed.), Social studies teacher education: Critical issues and current perspective (pp. 47-76). Information Age Publishing Inc.

Storey, V. J., & Cox, T. D. (2015). Utilizing TeachLivETM (TLE) to build educational leadership capacity: The development and application of virtual simulations. Journal of Education and Human Development, 4(2), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.15640/jehd.v4n2a5

U.S. Department of Education. (2016). The state of racial diversity in the educator workforce. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development.

Villegas, A. M., & Lucas, T. (2002). Educating culturally responsive teachers: A coherent approach. State University of New York Press.

Woods, D. M. (2021). Enacting number talks in a simulated classroom environment: What do preservice teachers notice about students? International Journal of Technology in Education, 4(4), 772–795. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijte.148

Zhang, S., & Cheng, Q. (2011) Learning to teach through a practicum-based microteaching Model. Action in Teacher Education, 33(4), 343-358. http://doi10.1080/01626620.2011.620523

Appendix A

Number Talk Reflection Directions

After the simulated number talk, reflect on your enactment by watching your video and summarizing your experience. Use the following prompts to guide your reflection.

Write a 1-to-2-page summary of your experience. Use evidence from the video (cite the time stamp) and connect to readings or course activities. Use these prompts to guide your reflection:

- What did you learn about your students’ mathematical thinking? Describe the solution strategies of 2 to 3 students (e.g., direct modeling, counting on/back, derived facts, etc.).

- How did you elicit, listen, and interpret student thinking (e.g., what questions did you ask, what talk moves did you use)? What worked? What didn’t work? What do you want to try next time?

- How did you enact equity-based practices for teaching mathematics? What worked? What didn’t work? What do you want to try next time?

- What did you learn about yourself as a teacher (e.g., what are your strengths, what do you need more time to learn)?

Social Studies Reflection Template

Watch your recording and use the following chart to analyze your experience. Remember, it is not expected that you would do all of the actions listed in the second column, rather use it as a way to analyze what you did or didn’t do. The goal is to allow this experience to be one of many in your teacher education preparation to grow as a well-started beginner advancing equitable practices in the teaching and learning of social studies (HT, EIST).

| Area of Work | Decomposition of EIST involving Social Studies (HT) | My Teacher Moves (provide evidence - time stamp) | Suggestions for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formulating and posing questions | |||

| Listening to and interpreting students’ thinking | |||

| Probing and unpacking what students say |

Appendix B

Focus Group Questions

The goal of the focus group was to gain an in-depth understanding of PST learning about high-leverage practices, as supported by their experience with mixed reality simulations. Three sessions were offered, with each session recorded and lasting roughly 30 minutes. The sessions were led by Carver with the help of a graduate assistant. Participation was voluntary.

Focus Group Questions

- Tell us your name and the class(es) and instructor where you used Mursion mixed reality simulations this semester.

- Tell us briefly about your experience with Mursion. How was it used in your class, e.g. what was the assignment and how did it connect to the class content? Probe: Was Mursion used to teach HLTPs?

- What were your favorite aspects of using Mursion this term? Similarly, what were your least-favorite aspects?

- How did Mursion prepare you to work with real students in real schools? Probe: Can you give an example of that? (Note: watch for the language of HLTP’s and draw that out if appropriate.)

- Do you think your perspective on using Mursion is influenced by the pandemic? Explain.

- Fast forward: it’s the future and you’ve graduated! You are in a job interview with your new principal and she asks about your readiness to solo teach. Do you share your experience with Mursion? Why/why not?

- Is there anything else you’d like to say about your experience with Mursion or mixed reality simulations?

![]()