Like schools and universities around the world during the 2020-2021 school year, we pivoted our Literacy Clinic to a synchronous, online platform. One of the first assignments we gave to the educators in our graduate seminar connected to the Literacy Clinic in 2021 was to view a youth-created theatrical performance focused on the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and ongoing systemic racism and racial violence (Teens Make History, 2020). The assignment read as follows:

Part of being an online literacy educator and literacy leader during COVID-19 (and beyond) is understanding the complexities of the dual pandemic. The dual pandemic refers to the public health crisis and how this exacerbates longstanding systemic racism in the lives of children and families. Watch the following youth-created theatrical performance; specifically, Episode 1 called “Can you hear me now?” This Zoom based dramatization focused on the realities of students in [our city] navigating the dual pandemics. After you watch, respond in the Discussion Board to these questions:

-How does this performance expand your understanding of the realities of the dual pandemics we are living through?

-This episode focuses on inequities and Internet connectivity. In what other ways do you see inequities manifested in online literacy teaching?

-How can we leverage digital tools to create humanizing critical literacies?

Inspired by critical literacies frameworks (e.g., Comber et al., 2001; Freire, 1970; Janks, 2000; Price-Dennis & Sealey-Ruiz, 2021), we sought to acknowledge our shared reality, question how these conditions are constructed through systems of inequity, reflect on our role as educators in this construction, and act to create conditions of peace, equity, and justice through our literacy teaching. The assignment sparked reflection, discussion, and semester-long inquiry from the group about centering the issues, concerns, and wonderings of students and families in their teaching.

During this time, we reassured the educators with whom we worked of a few things: First, we urged them to remember and call on their professional wisdom, knowledge, and practices of evidence-based effective literacy practices. Second, we asked them to resist deficit narratives about the pandemic-slide, especially as they were applied to Black and Brown families, and to center family knowledge and literacies in their instruction (Bang, 2020). Third, we invited them to not simply digitize their current practices but to imagine more robust, humanizing, and critical practices (Price-Dennis & Sealey-Ruiz, 2021). Fourth, we, assured them that we as white, anti-racist, critical teacher educators were also learning alongside of them; that is, there was not a blueprint for teaching literacy during a global pandemic (Duke & Morrell, 2020). We invited everyone to lean into the time of uncertainty and sought to study the emergence and transformation of critical literacies education in an online Literacy Clinic.

Our research was guided by the question, What happens when we invite educators to design critical literacies education in an online Literacy Clinic? The study described in this paper focused on an illustrative case study of one educator’s journey with critical literacies education from the launch of our online Literacy Clinic. Abigail, a white educator was matched with Zeke, an African American, first-grade student. Over the course of 12 weeks, Abigail’s pathway with teaching critical literacies online was brought to life as she built relationships, centered inquiry, and worked with her student to design a public service announcement (PSA) about recycling.

Synthesis of Scholarship

When we transitioned our University’s Literacy Clinic online, we had few cases to share with educators about of what literacy teaching (especially within critical frameworks) looked like in an online setting. Literacy Clinics refer to the space where teachers and K-12 students come together to teach and learn literacy in a supervised setting. At the heart of the Literacy Clinic model is the one-on-one or small group literacy tutorial, a collaborative learning community, and engagement with families. Indeed, clinics are unique in that they create space for parallel lines of inquiry and learning across teacher educators, K-12 educators and students, and their families (Dozier et al., 2005)

We reviewed research, policy briefs, and position statements from professional organizations, curated diverse e-book collections, created demonstration lessons, tried out platforms, and digitized instructional resources and practices that had previously been conducted in person. Educators enrolled in our Literacy Specialist program, like educators in general, felt underprepared to teach literacy in an online setting (Carpenter et al., 2020). By and large, teacher education programs and in-district professional development prior to March 2020 focused on teaching readers and writers in person. Some of this preparation included the use and development of digital literacies and teaching with technology and was geared for in-person teaching (Burnett & Merchant, 2018; Kalman & Rendón, 2014). That is, the field knows more about teaching literacy with digital media (e.g., Morrell, 2013) than in digital media (Beach & Tierney, 2016).

Teaching literacies online necessitates an awareness of the relationships between texts, students, and activities (Coiro, 2020). Indeed, alongside of pedagogical and content knowledge, teachers also must learn technological knowledge to keep pace with the rapidly changing digital world — a world that is, itself, structured by inequities, power, and multimodality. This means understanding the affordances and constraints of various texts being used, including those that are print-centric and in a fixed format, those that are multimedia and have interactive features (e.g., varying size of words, animated illustrations, and embedded sounds), and internet texts that may be fixed or active, multimodal and hyperlinked within the network of the Internet.

Teaching young learners who are still developing print-based literacies requires an understanding of “concepts of screens” (e.g., Pilgrim et al., 2018) alongside of the technological tools that will support students in online environments. Indeed, reading online – whether a fixed screen e-book or an interactive and hyperlinked text – requires complex and overlapping reading processes. For students developing word decoding, comprehension, and fluency strategies, reading any kind of text on the screen can be challenging because of the layers of visual, verbal, and textual modalities (Coiro, 2020). Other students may find the multimodality of hyperlinked, active texts to provide support they need as readers (e.g., pop-ups that provide pronunciation of technical terms and definitions, hyperlinks to a media clip, and play-based Apps; e.g., see Wohlwend, 2015).

Educators in our Literacy Clinic were quick to point out several challenges they had experienced teaching young children in online settings, including the difficulty of building relationships online, supporting young children with print literacies in a digital setting, connecting with parents, and maintaining their students’ focus on reading and writing. To address some of these concerns, we integrated into our seminars and coaching sessions short lectures from a developing body of scholarship focused on children’s meaning making with e-books and story Apps (McGeehan et al., 2018; Merchant, 2015; Ruetschlin Schugar et al., 2013), critical media literacy (e.g. Avila & Pandya, 2013; Morrell, 2013; Vasquez, 2014), and digital reading comprehension, which involves navigation, evaluation, and integration (e.g. Coiro & Dobler, 2007; Kiili et al., 2018), to contextualize our parallel lines of research and teaching in the Literacy Clinic.

We kept in mind that meaning making from written print is still of central importance for young students when reading on the screen in an online environment. At the same time, meaning is always made across interacting modes, and readers attend to these modes differently (e.g., Kress, 2010; Siegel, 2006; Simpson et al., 2013). Indeed, decades of scholarship demonstrates the ways multiliteracies instruction supports students to reach beyond the boundaries of written and verbal texts to use image, movement, sound, and layout as designs of new meanings (e.g. Siegel, 2006; Skerrett, 2011). We grounded our work theoretically in this tradition affirming that meaning making crosses an array of overlapping media worlds and invites questions about power, language, and action (e.g. Massey, 2005; Vargas, 2015).

Critical literacies refer to approaches to literacy instruction whose emphasis is on using technologies of print and other media to analyze, critique, and transform everyday realities (e.g., Dozier et al., 2005, Luke, 2000; Rogers & Mosley, 2014; Vasquez, 2014). These activities inherently include taking action and agency, important dimensions of critical literacy. Actions might be considered on a continuum, from questioning sociopolitical realities to reflecting on reading and writing about our roles in this realities to using literacies to design conditions of peace, equity. and justice (Rogers et al., 2016).

In our work with educators, we think it is important to emphasize the many routes to critical literacies teaching, including text-based, genre approaches (Kress, 1987), critical multiliteracies (Skerrett, 2011), and Freirean approaches (Comber, 2001; Freire, 1970; Souto-Manning & Yoon, 2018). We prefer an expansive umbrella because it allows room for educators to experiment, learn, and transform their practices (e.g., Mosley, 2010; Rogers & Mosley, 2014).

Much scholarship has shown the possibilities of critical literacies teaching with young children, particularly those at risk for difficulties with print literacies (e.g., Comber et al., 2001; Labadie et al., 2012; Souto-Manning & Yoon, 2018; Vasquez, 2014). Research clearly suggests that students need to be taught not only how to read multiple texts in critical ways but to create texts in digital environments (Aguilera, 2017; Bacalja et al., 2021; Janks & Vasquez, 2011). Yet, we know little about what this looks like in online learning contexts.

Inside the Design of Our Literacy Teaching/Research

Context of the Clinic

The University’s Literacy Clinic existed for more than 60 years as an in-person clinic held at the university or in a local elementary school. As a result of the COVID-19 shutdown, school closures, and pivot to online teaching, we designed a synchronous, online Literacy Clinic. The university is a large, metropolitan, land-grant institution located in the Midwest United States.

During the 2020-21 academic year, many school districts were online because of high COVID-19 infection rates during a time when vaccines were not yet developed or authorized. Educators and parents in school districts surrounding the university that primarily serve Black and Latinx students struggled with inequitable access to quality online literacy education. We provided online literacy tutoring without cost in our Literacy Clinic as an offering to families who lived within the footprint of the university and were most impacted by school closures.

The educators enrolled in the Literacy Specialist certification program taught in school districts around the region. There were 10 educators in this course. In this group was one educator of color. Others were White, middle-class women, some of whom were the first in their family to earn a graduate degree. All spoke English as their only language. Many students in the course had participated in some foundational professional development in culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy through their school districts.

We, the authors, are White, cisgendered female teacher educators with decades of experience and commitment of preparing critical literacy educators. Our approaches to critical literacies are inspired by our commitments to social justice and racial justice. We have both participated in dismantling racism workshops and have facilitated anti-racism workshops for educators. We all shared trepidation about the uncertainty of designing truly meaningful literacies education during this historical moment.

Educators enrolled in the program take six credits of practicum courses housed in the university’s clinic. Practicum courses include the following components: a 1-hour literacy tutorial, observations and debriefing with the course instructor, seminar discussions, viewing of recorded literacy lessons, written course assignments, and teachers’ communications with their student’s caregivers. Across the clinic experiences, we provide educators with various examples of critical literacies frameworks through readings, demonstration videos, case studies, and assignments to deepen and extend their knowledge and practice.

The course provides educators with the opportunity to put their understandings of literacy development, learning, and teaching into practice (e.g., Dozier et al., 2005). We integrate responsive literacy instruction within critical frameworks. Responsive literacy instruction is meant to help students who experience difficulty in reading and writing catch up to grade level peers through targeted literacy interventions within their zone of proximal development (Clay, 2003; Johnston, 2004).

We invite teachers to draw on their developing knowledge of critical literacies education and create an approach that is responsive to their student and engages with a problem or issue that piques their students’ interest (as in Comber et al., 2001). In this class, Lewison et al.’s (2014) Creating Critical Classrooms: Reading and Writing with an Edge was our core critical literacies text. The text offers a critical literacies model with four dimensions: focusing on the sociopolitical; taking social action; interrogating multiple perspectives; and disrupting the commonplace.

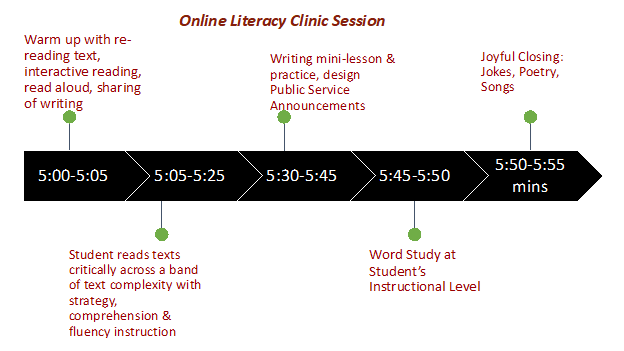

The Literacy Clinic was held on Wednesday afternoons. Teachers and students all joined a Zoom session and then were put into smaller breakout rooms for teaching. Figure 1 represents a typical schedule. Connected across space by time, joint activities that crossed media, and a virtual platform, collectively the teachers and students created what Massey (2005) referred to as a “place of being,” or what we referred to as an online Literacy Clinic.

Figure 1

Sample of Schedule for a Literacy Session

Teachers designed interactive digital slide decks (Google) for their online classrooms. Every teacher spent time during sessions taking running records of students’ reading, writing anecdotal notes about students’ literacy development, conferring with students about their writing based on their formative assessments, and administering assessments (e.g., Words Their Way Spelling Inventory). Many of the sessions focused on collaborative work between students, including critical discussions of read-aloud books and articles, researching topics of interest to the group, and designing PSAs to share at the end of the semester (Albers, 2011).

In our seminar and in coaching sessions, we encouraged teachers to create text sets or textual lineages (as in Muhammad, 2020; Tatum, 2009) that were connected in content and varied across the spectrum of digitality – from print-centric, fixed texts to interactive e-books, to hyperlinked Internet texts and media clips. These text sets provide a curricular conversation across the semester (e.g., Lewis & Ewing Flynn, 2017; McCaffrey & Corap, 2017; Sarker & Newstreet, 2016). Many of the teachers designed virtual bookcases that housed critical text sets focused on issues their students care about. The virtual bookcases included a range of genres and text levels, and K-12 students were invited to choose books from the virtual bookshelf to read together.

We relied on our university’s learning platform (Canvas) for the asynchronous components of the Clinic (e.g., reading literacy research and theory and submitting assignments), the Zoom video-conferencing platform for the synchronous clinical experience and seminar, and Google drive cloud-based storage for sharing teaching and learning materials, coaching feedback, and resources. Teachers in the clinic were practicing teachers, and many had access to online book collections such as EPIC, Raz-Kids, and Reading A-Z. In addition, we curated open access text collections (e.g., Unite for Literacy and ReadWorks) on the online platform, Wakelet. Teachers supplemented with interactive books, video clips, student created e-books, hyperlinked texts, and media clips.

Research Design

As professors of literacy education charged with leading the online Literacy Clinic and teaching the associated course, we taught and learned alongside Abigail and other teachers, students, and families in the clinic. We also designed a research study to observe, describe, and explain the details of critical literacy teaching in an online space.

At the beginning of the January 2021 semester, we invited teachers and parents to participate in the research study which would examine routine literacy teaching and learning that unfolded in the Literacy Clinic. (This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and consent was given from participants.) These artifacts included lesson plans and reflections, video-recordings of teaching and learning, class assignments, and observations of literacy teaching recorded in fieldnotes. In addition, we generated researcher analytic memos after each class session. As instructors in the course, we were participant-observers, and we provided feedback, resources, and demonstration lessons.

Case Study Design

Case studies can shed descriptive light on conceptual and practical questions. By concentrating on the nuances of a phenomenon under study researchers can illuminate patterns of practice (Merriam, 1988). As we observed Abigail’s teaching throughout the semester, we noticed how she addressed many of the concerns that we encountered about the difficulties of teaching critical literacies to young children online. Thus, we identified Abigail’s case as one that provides a generative illustration of teaching critical literacies in an online setting with a young student.

In addition, we generated a comprehensive record of her teaching across time that included parallel data sources (e.g., lesson plans, video-recorded teaching sessions, and surveys). This thick record of her teaching allowed us to investigate the contours of her case in a holistic manner as it unfolded across time. This was not the case with all of the teachers in the study, as some of their records were incomplete due to technological glitches (e.g., recording multiple break-out rooms within the Zoom video-conferencing platform).

The student with whom she was matched was Zeke, an African American first grader in a public school in a large urban school district. He attended school virtually several months during spring 2021. Zeke enjoyed basketball and playing with his friends. He enjoyed reading fiction books with animated characters and Minecraft, a videogame that allowed him to build simulated, virtual worlds. His mother registered him for the University’s Literacy Clinic because he was reading at the beginning of the first-grade reading continuum (B, C, and D level texts) and was aware that he should have been reading mid-first-grade level texts (E, F, G, and H level texts). She also noted that he had “limited comprehension.” She was worried about learning loss that was so widespread during school closures.

Abigail taught for 2 years in upper elementary prior to beginning her graduate work to become a literacy specialist. Her experience was in a primarily White, resourced school district. Due to the pandemic, she had some experience teaching literacy online, as she was teaching in person and had some students synchronously on Zoom. She was sensitive to issues of equity, particularly related to Internet connectivity and access to devices. During class discussions she positioned herself as wanting to learn more about critical literacies and equity.

Abigail was a reflective practitioner who carefully generated lesson plans and integrated feedback, theorized about the cause of breakthroughs and missed opportunities, and shared insights about her teaching and her students’ learning. For example, early in the semester she reflected on her strengths and areas where she needed additional support for her online literacy teaching. She reported relative confidence (i.e., 4 out of 5) in many areas such as “learning about students’ interests, questions, and concerns and build literacy practices that are responsive to these issues” and “assessing and guiding students’ decoding, reading comprehension, fluency, and writing when teaching online.”

She identified areas that she wanted to work on, such as reading fluency, which can “be tricky because of the time lag and connectivity issues,” finding diverse ways to connect with families’ funds of knowledge, and matching students with instructional level e-books that were culturally and linguistically responsive. About matching students to books in an online setting, she wrote,

I do not have much experience evaluating the quality of e-books. I usually try to read through the texts and look for quality content, vocabulary, and possible comprehension and critical literacy that students can learn from the text … I need more help with finding diverse eBooks.

To prepare for her first session with Zeke, she spent time reviewing e-books across a continuum of complexity that might be relevant and engaging for her student.

Data Collection

As part of the regular class routine, we asked teachers to keep a document trail that included their assessments, reflective notes, lesson logs, recordings of teaching, and case studies that documented their student’s progress. Over the course of the 12-week semester, we collected data on each component of the course. This case study is based on the following sources of data. Each of these data sources were analyzed with the research question in mind: When teachers are invited to design critical literacy practices in an online Literacy Clinic, what practices emerge overtime?

Literacy Lessons

Abigail designed and taught 12 literacy sessions. We recorded seven of the lessons. Each session included reading, writing, and word study within a focus on the environment. Abigail’s goal was to engage Zeke in reading and writing connected texts (80% of their time together) within a critical framework. The supporting documents for each lesson were housed in a Google online folder and included assessments, lesson logs and reflections, and student writing samples.

Observations and Conferring

We followed a coaching cycle in the observations of students in class. Each teacher was assigned a coteacher with whom they would cycle through premeetings, observations and debriefing (Rogers, 2014). We also observed lessons regularly and provided feedback.

During observations, we transcribed the lesson in an MS Word document that included two columns. On the left-hand side of the document, we kept a script of the observation, including nonverbal cues, uses of technologies, and kinds of texts and activities being introduced. On the right-hand of the column, we recorded questions, patterns noticed, and recommendations. At times, we provided in-the-moment or postteaching coaching through the chat function in Zoom. Our goal was to model a collaborative stance through our dialogue and feedback.

For example, we might name a practice we had observed (e.g., “I noticed you invited your student to act with his new understanding of pollution.”) or recommend a text that would extend their student (e.g., “Have you considered drawing on an Internet text?”) or question a problematic assumption at play (e.g., “I am wondering how else you might invite family knowledge into the lesson?”)

Seminar and Course Assignments

An important component of the Literacy Clinic is establishing a community of learners who inquire and solve problems together over time. This learning community is established in the seminar, through the course assignments, and in our debriefing and reflection times following teaching. In our seminar time, we met to discuss readings, analyze literacy teaching episodes, share resources, and celebrate breakthroughs in teaching and learning. We organized the readings and discussions by theme (e.g., strategy instruction, word study, craft lessons, and comprehension with criticality woven across the topics). One person in class was responsible for facilitating a discussion that corresponded with the focus of their recorded teaching. Following is a sample of how critical literacy was woven throughout the course:

- “Can you hear me now?” The Double Pandemic (Teens Make History, 2020)

View, Reflect, and Discuss - Analyze a Critical Literacies Lesson

- Critical Literacy Overview, Presentation and Discussion

- Invitation to attend Teaching for Change & Howard University virtual curriculum fair focused on Black Lives Matter at School

- Read & Discuss “Creating Critical Classrooms: Reading and Writing with an Edge”

(Lewison, Leland & Harste, 2007) - Develop Weekly Lesson Plans that include Critical Literacies

- Showcase Diverse Texts during Seminar Time

- Observe and Provide Feedback to Colleagues’ Literacy Teaching

- Public Service Announcements: Demonstration & Discussion

- Teacher-led Professional Development Session focused on Critical Literacy Invitation

- Final Community Celebration: Public Service Announcements

As course instructors, we used the seminar time to showcase how a digital resource such as Jamboard digital interactive whiteboard could provide a visual record of comprehension across a critical literacy text set or provide a demonstration lesson on creating PSAs with children using a combination of old (e.g., generating a storyboard on paper) and new technologies (e.g., reviewing examples of PSAs on YouTube). We recorded the seminars in ethnographic fieldnotes(Emerson et al., 1995).

Self-Assessment

All the educators in class completed a pre- and post-self-assessment to assess confidence on clusters of items related to teaching literacy online. These items included administering literacy assessments online, designing reading/writing/spelling interventions within culturally and linguistically responsive frameworks online, matching books to students, leveling e-books and curating diverse digital text sets, infusing critical literacies into online teaching, partnering with families, engaging in literacy leadership and coaching online, fostering a sense of joy, purpose, and agency online, and accessing, navigating, and creating digital tools for teaching literacy. Excerpts from the self-assessment can be found in Appendix A.

Analysis

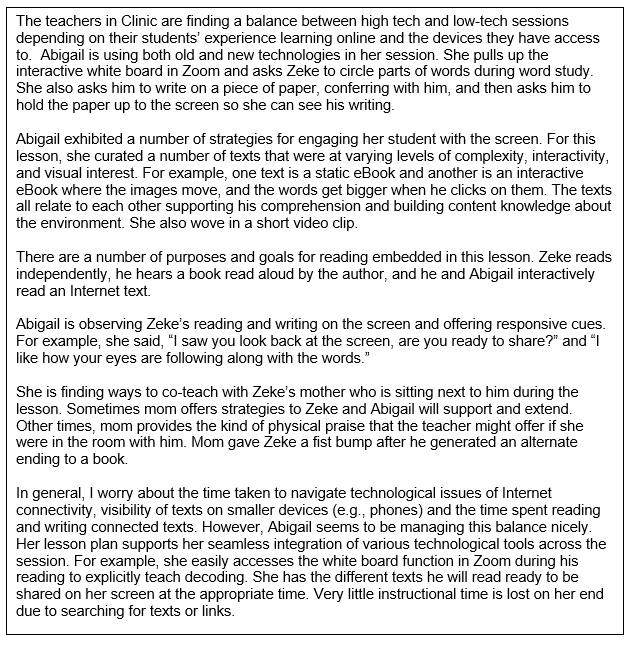

Data analysis occurred in an ongoing manner throughout and after the course. After class, we updated and organized the digital archives of each teacher. We kept analytic memos that were added to our observational notes, Mp4 audio files of recorded lessons, lesson logs, and other artifacts of teaching and learning. Figure 2 is an example of an analytic memo that highlights the development of analytic categories related to teaching critical literacies online. After the semester ended, we returned to the archives to analyze further the artifacts of critical literacy teaching that occurred across the semester using inductive, heuristic, and descriptive methods (Burawoy, 1998; Merriam, 1998; Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Figure 2

Analytic Memo Generated After Observation of Teaching, February 17, 2021

We chose a subset of Abigail’s literacy tutoring sessions that crossed time – from February through April – to analyze more closely. We designated these as “beginning,” “middle,” and “end” literacy sessions. Following our research question, we examined Abigail’s online critical literacies practices across time.

Generating transcripts of Abigail’s teaching sessions was an important part of the analysis. Our transcription process occurred in two different phases and included presenting or representing meaning across multiple modes (Cowan & Kress, 2017; Jefferson, 2004; Norris, 2004). Appendices B and C provide an example of the two phases of our transcription process for one segment of a lesson that occurred on March 11, 2021, where Abigail and Zeke’s mother supported him to write an alternate ending to a story.

Appendix B illustrates a vertically formatted transcript that privileges linguistic resources along with silences, pauses, and overlapping turns. There is also a verbal description of gaze, movement, laughter and shifts in activities in italics. Timestamps were an important feature of the transcript and allowed us to analyze the balance of time spent on different activities. Appendix C illustrates the second phase of our transcription process. To address the linguistic bias embedded in this transcript, we created a column-based transcript that foregrounds multimodality of the critical literacy episodes. On the left-hand side is a screen shot of the literacy practice, followed on the right by a summary description and infusion of dialogue from the verbal transcript (as recommended in Cowan & Kress, 2017; Norris, 2004).

Next, we identified critical literacy teaching episodes across the transcripts. We defined critical literacy teaching episodes as moments of teaching that included scaffolded analysis, critique, or transformation through the use of texts, dialogue, or activities. For example, Appendix B provides an example of a critical literacy teaching episode from a beginning lesson. Abigail’s goal was to scaffold Zeke to generate an alternate ending to a book he read from the tree’s perspective (purpose). She drew on his language experience (relationality), scaffolded him to consider another perspective (critical inquiry), and attributed agency and authorship to him when he did so (relationality).

We looked for examples of criticality in the texts, dialogues, and activities. We generated 11 codes across the critical literacy episodes. We then collapsed these codes into thematic areas: problem solving and inquiry, relationality (with student and parent), building intertextual connections, providing purpose, audience, and goals for literacy practices. These categories developed recursively from our herstories as teacher educators, researchers of critical literacies, first-hand observations of the teaching, and posthoc analysis. We also layered a descriptive and contextual dimension to our analysis, in which we sought to create a holistic understanding of this case (Merriam, 1998). In addition to our analysis of individual literacy lessons, we recontextualized interactions looking across data sources (e.g., surveys, reflective logs, lesson plans, and video-recorded observations).

Next, we generated tables that were analytic and representational devices meant to illustrate the categories of findings within a session and across the 12 weeks (see Tables 2-4). Each column includes a critical literacy teaching episode from the findings and a description of the texts, activities, and instructional dialogue that occurred during the episode. These tables became the basis of our written description of the findings, which we presented in a way that recognizes the overlapping nature of the categories of findings as they unfold across time. Finally, we recontextualized our analysis within the context of Abigail’s teaching unfolding across time and developed categories of findings that captured her critical literacies teaching over time: relationality, inquiry, and designing new meanings.

Findings

Building Relationships

Abigail set a relational tone of listening, inquiring, following Zeke’s interests, inviting his feedback, and partnering with his mother. She began with an interest inventory, which provided Zeke an opportunity to talk about his passions, expertise, concerns, and thoughts about changing the world (Comber et al., 2001; Dozier et al., 2005). During this time, Abigail humanized the instructional time by centering herself in the Zoom tile, providing nonverbal cues to let Zeke know she was attentively listening to him (e.g., nodding her head as he talked) and inviting humor, laughter, and fun into their session. In the first session, she invited him to choose from the virtual bookcase she created on a Google slide that represented a classroom. Abigail “roamed in the known” with digital texts, learning more about what Zeke knew about “concepts on the screen” (Kervin & Mantei, 2016).

During her first few meetings with Zeke, she brought print-centric texts to the screen focused on helping, rights, responsibilities, and taking action. This approach set a tone for action and agency that later developed into a PSA on recycling and environmentalism. She also invited Zeke to call on his expertise in Minecraft (a virtual game) during the writing portion of their lesson, connecting with his out-of-school literacies that served as a bridge between home and school. This step opened the door for this relationship building by drawing on the everyday, multimodal literacies that mattered in Zeke’s life (e.g., see Alvarez, 2016; Medina et al., 2015)

Zeke’s mom sat side-by-side with him during many of the early lessons to help him navigate technology, encourage him to show what he knew, and model interactional expectations of online learning (e.g., speaking loudly and pacing answers to questions). This engagement challenged Abigail’s prior experience connecting with parents. Previously, she had taken a traditional approach of hosting a curriculum night for parents, where she explained the expectations and objectives of each subject area and emailed parents when necessary (Debriefing, 2/21). She quickly realized that Zeke’s mom would be an active presence during the tutoring sessions, and she wanted to take an asset-based approach as we talked about in readings and seminar (Bang, 2020; Lazar et al., 2012).

Appendix D is a visual narrative that includes four columns that represent literacy practices representative of a typical beginning literacy session. Column 1 includes a screen shot of Abigail’s virtual classroom created with a Google slide that includes a virtual bookcase, plant, creatively decorated walls, and a teaching space that changes based on the focus of the lesson. In this episode, Abigail introduced some of the words he encountered in his first reading of this book.

Column 2 includes a screenshot as Abigail guided Zeke’s rereading of an on-screen book called We the Children (Guided Reading Level F, Unite for Literacy). She pulled up this open access e-book on her computer and shared her screen. This book has a repetitive text structure, approximately three lines of print per page, use of high frequency words, and realistic photographs of children around the globe engaged in the action featured in print. Abigail began, “In this book, remember we are talking about what children have the right to do. Last time, you told me you have a responsibility to go to school.” Taking less than a minute, Abigail evoked their last lesson where they previewed this book and talked about the rights and responsibilities that children have. Zeke’s interest had piqued as he talked about his right “to learn” and his responsibility to “clean my room.” With this teaching move, Abigail set up the expectation that readers build meaning across texts, modes, and time.

Abigail read the first page of the book to Zeke and then turned the page. “Now I want you to go ahead and reread these pages to me. Whenever you are ready.” Looking at the screen, Zeke read, “We have the right to learn. We have the right to play—” Zeke paused for a few seconds. His mom, who was sitting next to him, prompted him at the same time Abigail prompted him. They offered him different prompts:

Mom: “Look at the picture.”

Abigail: “Get your mouth ready to say that sound. What sound does ‘l’ make?”

As Abigail verbally prompted Zeke to look at the first letter, she also used the cursor to circle the word on the screen and then placed the arrow under the first letter of the word. Zeke responded, “l.”

This response can be seen in Column 2 of Appendix D.

Abigail: “l, laugh. Can you say laugh?”

Zeke: “laugh and —

Mom: “look at those first two letters”

Zeke: “dream.”

Abigail: “When we get to an unknown word, you can look at the pictures can help us with the letters and sounds. Getting our mouth ready to say the words.”

Abigail partnered with Zeke’s mom to support him as a reader who uses different sources of information. Additionally, she used the collective pronouns “we” and “our,” which signaled that they can collaborate as readers and writers.

Abigail navigated turning the pages, and Zeke continued reading, “We have the right to a family. We have the right to be loved.” By this point in his reading, his fluency increased, as he was familiar with the pattern in the book.

Zeke: “We have the right to be —”

Abigail: “This is a big word. We’re going to look at this word on the white board.”

Column 3 of Appendix D includes an image when Abigail pulled up the white board and wrote the word “protected” on the white board in red. She circled the prefix “pro” and engaged Zeke in word study. She changed her screen back to the book, and Zeke reread that page, transferring the problem-solving into text. Inquiring about the purpose of the text, she asked, “Why do you think the author wants someone to read this book?”

Zeke: “So they know their rights.”

Abigail: “It might help someone know and understand rights they have.”

This question, “Why do you think the author wants someone to read this book?” invited Zeke to think critically about the message in the text, the author behind the text, and the text as a social design. Abigail invited Zeke to “give yourself a round of applause.” They both engaged in the in-sync action of clapping, and there was a recognizable shift in the energy level of the lesson. (See Column 4 of Appendix D.) Indeed, across the sessions, Abigail and his mom consistently offered praise and encouragement to Zeke for problem-solving, which likely supported his development of a positive reading identity and confidence to work toward social action.

Centering Inquiry: Focusing on Environmental Science

Abigail and Zeke honed in on an environmental focus in their reading, something he had mentioned in the interest inventory. Zeke read on-screen books such as Counting the Stars and discussed how one’s geographical location impacts one’s access to viewing stars. He read Ready for Fall (Guided Reading Level F) about changing seasons, Race to Recycle (Guided Reading Level G) about recycling, and Ocean Animals (Guided Reading Level F) about marine life.

Their curricular conversations reached back to previous lessons and texts read and written. Throughout, Abigail wove critical literacies invitations, such as writing a different ending (e.g., “What else could the character have said on this last page? Let’s rewrite it.”), imagining different perspectives (e.g., “What might Earth look like within the virtual world of Minecraft?”), using evidence to support one’s sense of time (e.g., “How do you know when this photo was taken?”), and disrupting commonplace understandings (e.g., “Many people think that sharks are not intelligent…”). Each week, the texts Abigail offered Zeke were connected to the theme of the environment and human actions. They became increasingly complex and included different genres (e.g., informational text, biography, fiction, and reader’s theatre; Appendix E).

Abigail was eager to extend Zeke’s disciplinary knowledge about pollution from the sky to the ocean, engaging him to explore issues surrounding sustainability and environmental justice. She told him they were going to read an informational book about the oceans, called Ocean Animals (Guided Reading Level F). Appendix E, Column 1, represents an episode of her book introduction, with first author Rogers observing, as can be seen in the third Zoom tile on the screen.

Abigail previewed vocabulary and skimmed a few pages as part of her book introduction and asked Zeke to write down three ocean animals on a piece of paper, using his best spelling. She took this opportunity to activate background knowledge and extend his analysis of vowel patterns. He used inventive spellings to write the word “sting ray.” Abigail pulled up the white board in Zoom to show Zeke different letter pairs that say “ay,” like “ai.” After the introduction of vocabulary words and the preview of a diagram, Zeke read the text for the next 6 minutes. During this time, the book was projected on the screen (see Column 2, Appendix E). Zeke read in a word-by-word manner, looking at the screen: “Some ocean, some animals live in the water at the top of the ocean. They jump out of the water. They like to play.”

Abigail engaged Zeke through inquiry into his problem solving, “And up here you said ocean originally, what made you go back? What made you go back and reread that?”

Zeke: “Because, because I didn’t see…”

Abigail: “Did it sound right to you?”

Zeke: “Mm-hmm (negative).”

Abigail: “Did it make sense?”

Zeke: “Mm-hmm (negative).”

Abigail: “So you went back, you self-monitored. You realized that didn’t make sense there, so let me go back and let me see what it said and then you realize, ‘Huh, that doesn’t say ocean, that says animals.’ Great job, that’s what great readers do.”

Looking closely at Appendix E, Column 2 and 3, one can see the empty chair next to Zeke. This is the chair that Zeke’s mom pulled over to the desk every session. By the middle sessions, her presence focused on helping him log in, solving technological issues focused on Zoom, and providing verbal reminders to “speak up” or to “pay attention.” It was clear that his mom was still present and engaged, just outside of the Zoom frame, playing a supportive role but less focused on instructional prompts. Sometimes, she would sit down in the chair and co-observe with interest what Zeke was reading or writing on the screen.

Appendix E, Column 2, focuses on the page in the on-screen book that Abigail used to guide his reading of a diagram.

Zeke [reading]: “…Some of the animals that live in the ocean have fins to help them swim.”

Abigail: “Nice job, yeah. … How does this diagram help you as a reader?”

Zeke: “So you can see the different part if you don’t know them.”

Abigail: “It helps give you some more information if you don’t know all of that. So remember last week we talked about recycling. What are some ways you can help?”

Abigail used language that attributes potential agency to him, increasing the likelihood that he will take action in and out of texts in the future.

Zeke: “You could recycle your trash and all the things on the floor and help the environment.”

Abigail: “Yeah, it helps the environment if we recycle, right? That way we don’t get pollution. And what I mean by that is we don’t get bad things to go out into the air and into the environment. So just like we have pollution in the air, we also get ocean pollution. And I’m going to show you a picture what I mean by that. So if you look at this picture, what do you see in this picture?”

Zeke: “I see a turtle eating trash and he might get sick and die.”

Abigail: “How do our actions as humans affect other living beings?”

Zeke: “Because we’re not keeping the environment clean.”

Abigail revoiced his idea and emphasized the positive actions that we can take: “We need to do our part to keep everything clean.” Zeke had more to say: “If the earth was all junky, we wouldn’t be able to walk around. We would just slip on all of the trash.”

This 2-minute episode illustrated the power of an intentionally chosen image to spark critical inquiry into a big idea (Freire, 1970). In this case, Abigail supported Zeke to reach toward the question, “How do our actions impact life on the planet?” The image she chose connected thematically with the book he read about Ocean Animals. It also introduced a more complex idea – how pollution endangers animals – than was available in the Guided Reading Level F text.

Appendix E, Column 3, represents Abigail’s transition to critically reading another image, this time of a map of the United States that showed the connections between rivers and oceans. Abigail’s dialogue scaffolded his critical reading of these images, connecting them to the big idea of how human actions impact life on the planet. The online context provided her with the affordance to bookmark images she found on the internet and quickly display them, extending the content and text complexity. Van den Broek et al. (2009) pointed out that “it is the strategic use of the various media in such a way that the comprehending child engages in relevant processes in which he or she otherwise would not engage” (p. 69).

Abigail: “Here we have a map. Where do we live on the map? Do we live near an ocean?”

Zeke: “No.”

Abigail: “Do our actions effect the ocean?”

Zeke: “Yes, because our trash will spread and then other people’s trash will keep doing it, and doing it, until it get to the ocean, and the world, and the entire planet.”

His voice grew increasingly animated as the impact of the actions expand outward to the “entire planet.”

Abigail: “Yeah, what connects us to the ocean?”

Zeke: “A river.”

Abigail: “We have the Missouri river and the Mississippi River.”

Zeke: “…that means if we throw the trash away, it will go to the stream, and the river, and then it goes to the ocean and then it gets filled with trash.”

After we observed Abigail’s lesson, we asked her to be more intentional about choosing literature that centered African American scientists, so Zeke could see himself in the texts (fieldnotes, 3/17/21). Abigail integrated this feedback into the design of her lesson plan. Appendix E, Column 4, represents a transition to a video of a read aloud of the book Hidden Figures (Shetterly & Freeman, 2018), which Abigail accessed on YouTube. The video focuses on the book and the video angle changes. On each page, there are subtitles of the words being read. Thus, there is movement, images, the reader’s voice, and print woven into this read aloud experience.

The content of the book focuses on the story of a team of African American women mathematicians who played a critical role in NASA during the early years of the US space program. Abigail chose a high-quality piece of children’s literature with more sophisticated content and literary features to build Zeke’s background knowledge and vocabulary. She noted in her reflections, “We read a lot of diverse read alouds about characters from different backgrounds and races. We also looked at power differences and female and male scientists and authors” (Lesson Reflections, 3/21). As she brought the video of the read aloud to her screen and set a purpose for reading, she said, “Today, we’re going to look at oceanographers who study maps and use reading and writing all day long. Can women be oceanographers and scientists?” For the next 5 minutes of the lesson, they coviewed Hidden Figures. She stopped the video periodically to scaffolded his inquiry into the multimodal text and its meanings.

Abigail invited him to transfer the craft lessons about labeling informational texts to his expertise about Minecraft. After writing, Zeke held up the page he had been working on to show Abigail and said, “Isn’t it amazing?” and then, “I’m a good drawer.” Abigail confirmed this and said, “You are. You’re good at a lot of things.” Abigail accepted Zeke’s autonomy as a writer and praised his work, which reinforced his confidence that he was able to make design choices using multiple modalities to engage his audience. Column 5 of Appendix E is a screen shot of Zeke’s Minecraft drawing and writing.

Designing and Sharing a PSA

Abigail continued to invite family knowledge and practices in her lesson plans to design new meanings. Abigail noted,

Zeke and his mom were able to discuss what they do at home for recycling. They shared a picture of their garden and composting bins. This allowed Zeke to connect what he was doing at home to what he was teaching his peers in the Clinic.

They continued to critically read images of the world, noticing the presence of oceans, land, and the equator. Toward the end of their sessions (9-12), the writing shifted to designing the PSA focused on how human actions impact the environment. Albers (2011) wrote,

As a genre, PSAs are … a type of advertisement intended to raise awareness of an issue, and potentially initiate social action. PSAs often address social issues … use multiple modes to convey meaning (e.g., visual, linguistic, spatial, musical, temporal) and are targeted towards populations of all ages. (p. 48)

Abigail showed Zeke a PSA created by children about recycling to introduce him to the genre. They coviewed the video and mentor text PSA called “Kids Recycling” (Video 1). Abigail’s questions in her lesson plan included, “How is this PSA designed? Who is the audience? What modes did they use?” She guided him to critically analyze how designers make meaning so that, he too, could be a creator of media.

Video 1

Kids Recycling

Zeke had read or coviewed several e-books about recycling and played an online game about recycling. Abigail focused on the comprehension strategy of identifying cause and effect (human actions and impact on the environment). Appendix F includes representative images from a lesson that illustrates the diversity of literacy practices that Zeke was immersed in across this 1-hour lesson. These practices are connected thematically, range in text complexity, are modally dense, and offer different opportunities to generate critical literacies.

Abigail explained they would be revising their PSA, adding images to the content he had already generated. In Appendix F, Column 1, Abigail guided Zeke to choose an image to extend the meaning on the slide, which read, “How can we help prevent the problem?” “Not littering; Throwing away trash; Reuse items, Recycle.” Abigail had pulled up an image search from Google.

Abigail: “Are there any other recycling images that you want to include?”

Zeke: “The one where it shows the recycling bin and someone’s holding it.”

Abigail: “This one?”

Zeke: “Mm-hmm (affirmative). It shows all the other dumpsters in the back.”

Abigail: “Making sure everything goes where it needs to.”

Abigail pasted the image on the slide. Zeke chose an image that emphasized the human action of holding a recycling bin, his attention focused on actions embedded in images and words. Zeke commented about her design choice: “That’s big too, it’s really big.” Abigail responded, “It is big, I’ll make it smaller for you.”

They engaged in collaborative problem-solving about the content, placement, and size of the image. Abigail used a modified language experience approach, asking Zeke to share what he had learned about recycling and keeping the Earth clean. She wrote on the slide, scripting his ideas in a fashion similar to the way a teacher might use chart paper in their classroom. She advanced to the last slide that read, “Contract to save the Earth.” This can be seen in Column 2 of Appendix F.

Abigail reread this slide to Zeke:

And then we have our contract to help save Earth. So you said we should recycle and put your items in the correct bins, you should make sure you put everything in the trash or recycling every day. You should try to reuse different items so there’s less trash and it saves you money. Doing this helps animals so they don’t get hurt or stuck and then they wouldn’t be able to get out. Oops, that meant to be the same one. And then here’s your last statement that you wanted to tell everyone was let’s not make the whole world a trash land. What do you think we could add as a picture for this one?

The memorable idea – an important component of PSAs – that Zeke wanted to emphasize was that people should not make the world a “trash land.” Abigail followed Zeke’s lead consistently – from the choice of topic, to identifying images, to generating search terms for Google and arranging the print and images on a slide with an audience in mind.

Abigail reminded Zeke of his main point: “Let’s not make the whole earth a trash land.” She captured his idea on the slide and they turned to choosing a corresponding image. This was a collaborative endeavor with her scrolling through the images that were pulled up on her computer and visible to Zeke through screen share. She controlled the scrolling, but he verbally directed what she chose. She asked him, “What do you want me to look up?” This interaction is captured in Column 3 of Appendix F. Zeke responded, “Trash, trash lands.”

Trash lands is a concept from a child’s perspective that is evocative and compelling. Without skipping a beat, Abigail typed in “trash land” into the search bar and instantly a page of images appear on the screen. She said, “Trash land, let’s see. Wow we have a lot of trash. Wow, that’s crazy. Can you imagine – Zeke, seeing one that caught his interest, said, “The one, the one, uh, with the sunset.” Abigail asked, “This one?” Zeke affirmatively responded, “Mm-hmm. It looks kind of pretty a little.”

He verbally directed Abigail to stop at an image that represented a sharp contrast between a pink/orange sky and a sea of trash in front of it. Abigail challenged his interpretation of the image in light of their focus on recycling. She offered a different perspective, “The sky is pretty. Is the ground pretty?” Zeke responded, “No.”

Rather than stop with critique, Abigail invited Zeke to redesign in light of their focus on recycling. She said, “No. But you can make it pretty by doing what?” Her question was not immediately taken up. Zeke considered his expanding interpretation of the image. He said while looking at the image, “The ground, trash, trashy.” Abigail agreed with his analysis and revoiced his point, “It is trashy.” She copied and pasted the image onto their slide-in-progress. Zeke watched as she demonstrated his and offered feedback on the layout and design.

Abigail shifted gears to read the book, The Mess We Made (Lord & Blattman, 2020), which is an approximate Guided Reading Level M/N. This activity can be seen in Column 4 of Appendix F. With repeating, cumulative lines and plot and a rhythmic pattern, this interactive e-book focuses on the human cause of ocean pollution, an environmental issue that sustained Zeke’s curiosity across time. Abigail read aloud several pages of the book:

This is the mess we made. These are the fish that swim in the mess we made. These are the seals that eat the fish that swim in the mess we made. This is the net that catches the seal that eats the fish that swim in the mess we made.

Abigail shifted the authority of reading to Zeke, and he read the next page with support. She guided Zeke’s reading of the illustrations and words, transferring knowledge and building awareness of how human actions impact oceans. Appendix F, Column 5, illustrates this part of the lesson.

Abigail, asked, “What do you think of this picture? Is this the type of ocean that you want to swim in? Or how– Is this what, is this what the ocean should look like?” Zeke responded, “It’s clean, no trash, all, none of the fish have like plastic things sticking to them.” This exercise invited Zeke to imagine an ocean free of pollution, an important part of designing new meanings.

Appendix F, Column 6, is a screenshot of Zeke recording his PSA over the slides. Zeke’s recorded PSA was played at the Literacy Clinic celebration the following week. His last slide was a “contract to help save the Earth!” This included his specific asks to his audience: “You should recycle and put items in the correct bins. You should try to use reuse different items so there is less trash and it saves money!” And “Let’s not make the whole earth a trash land.” In this session, Zeke and Abigail designed the PSA drawing on all of the affordances of an online critical literacies teaching: coinvestigating images through an internet search, codesigning a slide for their PSA, reading a compelling e-book, and recording the PSA through the online platform. His mom was in the audience enjoying Zeke’s presentation.

At the end of the semester, Abigail revisited the self-assessment and realized she extended her technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge of teaching critical literacies to a young student. All of the items where she had rated herself as low in confidence (“2”) were rated as a “4.” In her postsurvey she indicated that locating diverse, instructional level e-books was an area of growth for her and mentioned several new, multicultural collections she used. She wrote, “I used a lot of diverse read alouds to foster critical literacy. I also tried to find books on Unite for Literacy that matched my student’s reading level.” She gained more experience carefully looking at text complexity and critically scaffolding Zeke to read the word and the world. At the end of the semester, Zeke’s mom wrote, “It has been an absolute pleasure working with Ms. Abigail and the Literacy Clinic. Zeke’s confidence in reading has grown strong; and his love for reading is developing.”

Discussion and Conclusion

There is no blueprint for teaching critical literacies during a global pandemic of COVID-19 and continuing systemic racism. Together, we responded to the question we posed at the beginning of the semester: How can we leverage digital tools to create humanizing critical literacies? We have focused our analytic attention on a teacher’s journey of practicing critical literacies with a young student to extend the field’s understanding of the possibilities (and continued barriers) of teaching in online learning contexts.

Abigail used the affordances of the online environment, including access to multiple text types along a spectrum of complexity, critical inquiry into a social issue, a multimedia project that was shared with an online audience, and being in her student’s home to invite family knowledge into the lesson. Focusing on environmental sustainability is one of the most pressing issues of our time. Abigail followed Zeke’s interest and family knowledge about the environment and recycling in a problem-posing, problem-solving manner. She provided critical scaffolding for him to read the word and the world. Abigail established conditions for Zeke not only to read texts critically but to engage in the design of new meanings through his PSA.

Appendixes D, E, and F include representative episodes which, together, create a visual narrative of the interplay between texts, activities, and instructional dialogue that supported relationality, inquiry, and designing new meanings over time. Following her student’s lead, Abigail curated diverse textual encounters with him, drawing on a spectrum of text complexity. Across the sessions, her practices connected thematically to the environment, ranged in text complexity, were modally dense, and offered opportunities for building disciplinary knowledge (Tatum, 2021).

For example, Abigail partnered a static print-centric informational e-book about the oceans with a multimedia piece of literature also about recycling and the oceans. The visuals of scrolling text and movement of animals and litter in the ocean offered new challenges for Zeke as a reader, which were mitigated by his developing background knowledge of ocean life. Thus, educators might think about text complexity not as constrained to any one single text but to a configuration of print and digital texts that, together, create a level of complexity. Indeed, this is another affordance of online literacy teaching. The text complexity increased over 12 sessions. From fixed format e-book at a GRL F, to reading maps, to viewing Hidden Figures (GRL N text), to a shared reading of a GRL M/N text, Abigail supported Zeke to read increasingly complex texts through the thematic focus on the human actions and the environment.

The appendixes provide a visual narrative of the literacy activities and instructional dialogue that were student centered and inquiry based and had a purpose, goal, and audience in mind. Rather than stopping with critically reading texts about the environment, Abigail also engaged Zeke with designing a PSA. Abigail illustrated the central role literacy educators play in collaboratively orchestrating learning experiences with students in online learning environments. Whether in person or online, collaborative teacher talk is important as a scaffold to new learning (Simpson, 2010). Appendixes D, E, and F provide a sample of Abigail’s invitational teacher talk that characterized the lessons. Across the narrative episodes developed in the case study, Abigail coconstructed instructional dialogues that centered inquiry and collaborative digital problem-solving. This came to life in the design of the PSA, where she modeled searching and navigating, guiding her student to participate in this process and providing him with feedback on their independent practice.

One of the barriers to teaching critical literacies often cited by educators is their fear of parental resistance (Hendrix-Soto & Mosley Wetzel, 2018). An important finding from this case study is that Abigail built a relationship with her student’s mother in meaningful ways that were central to her critical literacies teaching. When Zeke’s mom pulled up a chair next to him during the tutoring sessions, Abigail knew she needed to rethink her approach to engaging families. She welcomed his mom’s physical presence as she sat next to him and offered Zeke suggestions. Most importantly, she moved beyond asking Zeke’s mom to reinforce her teaching. She invited her knowledge and expertise into their sessions; centering their family knowledge and practice of recycling and composting.

This became a point of departure for his continued learning and PSA on this topic. More than an aside, Abigail and Zeke faced the enduring tension of technological advancements and environmental destruction head on. It is worth emphasizing that this focus on sustainability and environmental justice had roots in Zeke’s family. Interestingly, Zeke’s mother gradually released her support across the sessions. In the beginning sessions, she sat side-by-side with him offering instructional strategies. Abigail creatively wove these prompts into her own instructional dialogue, demonstrating the value of partnering with his mother. By the middle sessions, Zeke’s mother was always nearby and listening but did not coview the screen for the entire session. Her engagement included helping him navigate technological issues, providing him with literacy supplies or reminders to speak up, listening with interest.

Importantly, Abigail had demonstrated that she valued their family knowledge – both in terms of her physical presence, their family knowledge, and the collaborative teaching support she offered. By the end of the sessions, Zeke’s mother was not physically present during the lessons, but their family expertise about recycling was at the center of the lesson. In the final celebration, she was an audience member as Zeke presented his PSA. Thus, collaborating with Zeke and his mother were central in her journey of designing critical literacies. We highlighted this dynamic across the paper to emphasize the labor of women and Black women, in particular, that was often made invisible during the dual pandemics. Additional research is needed on the role technologies, spatiality, and relationality play in interactions between parents and educators.

While the case study design allowed us to engage in a more granular analysis, zooming in on the critical literacies practices of one teacher, it is also necessary to consider the larger context. Here, it important to widen the lens to remind readers that Abigail was part of a community of learners in our Literacy Clinic. While we have attended to the details of how one teacher engaged with critical literacies teaching online, she did so alongside of other educators doing the same. As teacher educators, we modeled a stance of criticality and inquiry in the entire design of the Literacy Clinic, course, assignment, and expectations that the semester would culminate with a student generated PSA. This critical media project kept our collective attention focused on critically reading and composing texts with a purpose, goal, and audience in mind. In the final celebration, students from the Literacy Clinic displayed PSAs focused on disability studies, Black Lives Matter, environmentalism, and gender fluid fairytales, among others. Thus, Abigail’s experimentations with her practice were in a community of learners doing the same.

A barrier that Abigail and other educators in our clinic faced was the limited amount of time they had with their students. Indeed, they only met once a week for 1 hour. As a result, Abigail was faced with the tension of following her student’s interests and orchestrating texts, activities, and instructional dialogues in a manner that was relevant and engaging, while being mindful of the limitations of time. Likewise, with more time, we could have supported Abigail to explore a more explicit racial analysis of environmental justice issues. For example, we might have started a discussion about the disproportionate presence of contamination sites located in Black and Brown communities and how these toxic materials leech into waterways. She, in turn, could provide place-based examples of this problem in Zeke’s region so he could see the relevance of his family’s interest in the environment. Likewise with more time, he might have shared his PSA with a broader community of activists in our region working on environmental issues so Zeke could see and feel the power of working alongside a community of people.

A related barrier in our teacher education program is the lack of required courses focused on critical social theory. Inviting critical literacies into teacher education requires an education in social, political, racial, and economic theory. How do we teach educators to critique and transform inequitable systems at the same time they are building an understanding of these systems? In this course, we began by centering our shared experiences during the dual COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing racial violence. Together, we named inequities and our roles in these systems. We grew in our realization that critical literacies are especially important in tumultuous times. Yet, many educators have not read and created their own understandings of primary texts such as Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed or bell hooks’ (1994) Teaching to Transgress or Derrick Bell’s (1992) Faces at the Bottom of the Well. This is a barrier to truly pushing forward with the project of critical literacies in schools, especially during times when theoretical foundations such as Critical Race Theory are under attack (African American Policy Forum, 2022).

We know of no other studies that focus on critical literacies education within online Literacy Clinics. Literacy Clinics have a long history in the field of teacher education in preparing literacy specialists, and many are experimenting with online and hybrid structures (e.g., Vokatis, 2018). Further research and development is needed is this area. While this case study focused on the experiences of Abigail, it addressed many of the uncertainties all educators experience as they design literacy lessons for online learning contexts.

Abigail wove together technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge of literacy to design literacy sessions. She called on what she knew, was open to innovations, theorized about her practice, and was responsive to family knowledge. It is important that we continue to gather evidence about how educators design critical literacies with young students during online literacy teaching. For example, we need more research on how teachers learn about, use benchmark texts, and navigate text complexity and textual lineages (Tatum, 2009) across texts such as fixed and active e-books, hyperlinked internet texts, and other media designs.

We also need more research on the ways teachers recognize and follow students’ reading and writing pathways in online environments and the discourse practices of critical scaffolding within online literacy teaching. Abigail’s case focuses specifically on critical literacy teaching online with an early reader, while inquiry into working with more experienced readers might provide other insights. Abigail also had a range of supports (feedback and coaching from literacy faculty, a supportive peer community, access to a range of e-books, etc.) that helped her to meet Zeke’s needs. How might teachers in other settings leverage supports to foster critical online literacies with students?

Educators around the world have committed to creating digital pathways to teach young children to read and write in ways that are responsive to the current realities. The study provided us with the opportunity to observe, make adjustments to the class, and also to slow down teaching practices after the class ended to study them more closely. Indeed, as online literacy teaching continues to be a presence – not merely a pandemic patch – it is important to ensure the transfer of responsive literacy instruction within critical frameworks, at the same time, making space for pedagogical innovations afforded by online learning contexts. Our hope is that this case study provides a thick description for educators, Literacy Clinic directors, teacher educators, tutors, and parents stewarding learning at home.

References

African American Policy Forum. (2022). How reclaiming anti-racism can save our democracy: Lessons from the frontlines. The New Press.

Aguilera, E. (2017). More than bits and bytes: Digital literacies on, behind, and beyond the screen. Literacy Today, 35(3), 12-13.

Albers, P. (2011). Double exposure: A critical study of preservice teachers’ multimodal public service announcements. Multimodal Communication, 1(1), 47-64.

Alvarez, J. (2016). Social networking sites for language learning: Examining earning theories in nested semiotic spaces. Signo y Pensamiento, 35, 35–68.

Avila, J., & Pandya, J. (2013). Critical digital literacies as social praxis: Intersections and challenges. Peter Lang Press.

Bacalja, A., Aguilera, E., & Castrillón-Angel, E.F. (2021). Critical digital literacy. In J. Pandya, R. Mora, J. Alford, N. Golden, & R. de Roock (Eds.), The handbook of critical literacies, (pp. 373-379). Routledge.

Bang, M. (2020). Towards midwifing the next world: How can being and doing make openings in these times? [Webinar]. Speculative Education Colloquium. http://www.theamericancrawl.com/?p=1797

Beach, R., & Tierney, R. J. (2016) Toward a theory of literacy meaning making within virtual worlds. In S. Israel (Ed.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (Vol. 2.; pp. 135-164). Guilford.

Bell, D. (1992). Faces at the bottom of the well: The permanence of racism. Basic Books.

Burawoy, M. (1998). The extended case method. Sociological Theory, 16(1), 4-33.

Burnett, C., & Merchant, G. (2018). New media in the classroom: Rethinking primary literacy. Sage.

Carpenter, J. P., Rosenberg, J. M., Dousay, T. A., Romero-Hall, E., Trust, T., Kessler, A., & Krutka, D. G. (2020). What should teacher educators know about technology? Perspectives and self-assessments. Teaching and Teacher Education, 95, 103124. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2020.103124

Clay, M. (2003). Observation survey of early literacy achievement. Heinemann.

Coiro, J. (2020). Toward a multifaceted heuristic of digital reading to inform assessment, research, practice, and policy. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(1), 9-31.

Coiro, J., & Dobler, E. (2007). Exploring the online reading comprehension strategies used by sixth-grade skilled readers to search for and locate information on the Internet. Reading Research Quarterly, 36, 378-411.

Comber, B., Thomson, P., & Wells, M. (2001). Critical literacy finds a “place”: Writing and social action in a low-income Australian grade 2/3 classroom. Elementary School Journal, 101(4), 251-264.

Cowan, K., & Kress, G. (2017). Documenting and transferring meaning in the multimodal world: Reconsidering “transcription.” In F. Serafini & E. Gee (Eds.), Remixing literacies: Theory and practice from New London to new times (pp. 50-61). Teachers College Press.

Donohue, C., & Schomburg, R. (2017). Technology and interactive media in early childhood programs: What we’ve learned from five years of research, policy, and practice. Young Children, 72(4), 72-78.

Dozier, C., Johnston, P., & Rogers, R. (2005). Critical literacy/critical teaching: Tools for preparing responsive teachers. Teachers College Press.

Duke, N., & Morrell, E. (2020). Literacy teaching in turbulent times [Webinar]. International Literacy Association. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sq5Dr_G1U4A

Emerson, R. Fretz, R., & Shaw, L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Hendrix-Soto, A., & Mosley Wetzel, M. (2018). A review of critical literacies in preservice teacher education: Pedagogies, shifts, and barriers. Teaching Education, 30(3), 1-17.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Jacobs, G., & Castek, J. (2022). Collaborative digital problem-solving: Power relationships, and participation. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 65(5), 377-387.

Janks, H. (2000). Domination, access, diversity, and design: A synthesis for critical literacy education. Educational Review, 52(2), 175-186.

Janks, H. & Vasquez, V. (2011). Editorial: critical literacy revisited: writing as critique, English teaching: Practice and critique, 10(1), 1-6.

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13-31). Benjamins.

Johnston, P. (2004). Choice words: How our language affects children’s learning. Stenhouse.

Kalman, J., & Rendón, V. (2014). Use before know-how: Teaching with technology in a Mexican public school. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27, 974–991.

Kervin, L., & Mantei, J. (2016). Assessing emergent readers’ knowledge about online/reading. The Reading Teacher, 69, 647-651.

Kiili, C., Leu, D., Utrainen, J. Coiro, J., Janniainen, L., Tolvanen, A., Lohvansuu, K., & Leppanen, P. (2018). Reading to learn from online information: Modeling the factor structure. Journal of Literacy Research, 50, 304-334.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge.

Kress, G. (1987). Genre in a social theory of language. In I. Reid (Ed.), The place of genre in learning (pp. 35–45). Deakin University Press.

Labadie, M., Mosley, M., & Rogers, R. (2012). Opening spaces for critical literacy: Introducing books to young readers. The Reading Teacher, 66, 1-12.

Lazar, A., Edwards, P., Thompson McMillon, G. (2012). Bridging literacy and equity: The essential guide to social equity teaching. Teachers College Press.

Lewis, W., & Ewing Flynn, J. (2017, Fall). Below the surface level of social justice: Using quad text sets to plan equity-oriented instruction. ALAN Review, 22-31.

Lewison, M., Leland, C., & Harste, J. (2007). Creating critical classrooms: K-8 reading and writing with an edge. Routledge.

Lord, M., & Blattman, J. (2020). The Mess We Made. Flashlight Press.

Luke, A. (2000). Critical literacy in Australia: A matter of context and standpoint. Journal of Adolescent & Adult and Literacy, 43(5), 448-461.

Luke, A. (2012). Critical literacy: Foundational notes. Theory into Practice, 51(1), 4-11.

Massey, D. (2005). For space. Sage.

McCaffrey, M., & Corap, S. (2017). Creating multicultural and global text sets: A tool to complement the CCCS text exemplars. Talking Points, 28(2), 8-17.

McGeehan, C., Chambers, S., & Nowakowski, J. (2018). Just because it’s digital, doesn’t mean it’s good: Evaluating digital picture books. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 34(2), 58-70.

Medina, R., Ramírez, L., & Clavijo, A. (2015). Reading the community critically in the digital age: A multiliteracies approach. In P. Chamness, M. Mantero, & H. Hendo (Eds.), ISLS readings in language studies (pp. 45–66). ISLS.

Merchant, G. (2015). Keep taking the tablets: iPads, story apps, and early literacy. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 38(1), 3-11.

Merriam, S. (1998). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Sage Press.

Morrell, E. (2013). Critical media pedagogies: Teaching for achievement in city Schools. Teachers College Press.

Mosley, M. (2010). Becoming a critical literacy teacher: Approximations in critical literacy teaching. Teaching Education, 21(4), 403-426.

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic.

Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction: A methodological framework. Routledge.

Pilgrim, J., Vasinda, S., Bledsoe, C., & Martinez, E. (2018). Concepts of online text: Examining online literacy skills of elementary students. Reading Horizons, 57(3), 68-84.

Price-Dennis, D., & Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2021). Advancing racial literacies in teacher education: Activism for equity in digital spaces. Teachers College Press.

Rogers, R. (2014). Coaching teachers as they design critical literacy practices. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 30(3), 1-21.

Rogers, R., & Mosley, M. (2014). Designing critical literacy education through critical discourse analysis: Pedagogical and research tools for teacher researchers. Routledge.

Rogers, R., Mosley Wetzel, M., & O’Daniels, K. (2016). Learning to teach, learning to act: Becoming a critical literacy teacher. Pedagogies, 11(4), 292-310.

Ruetschlin Schugar, H., Smith, C., & Schugar, J. (2013). Teaching with interactive picture e-Books in grades K-6. The Reading Teacher, 66 (8), 615-624.