At the time of the study, acts of racism and police violence were — and, unfortunately, continue to be — frequent in the lives of Black people and displayed in mainstream and social media. In the years 2015 through 2019, roughly 23% of unarmed people killed by U.S. police each year were Black men, even though Black men comprised only 6% of the U.S. population (Washington Post, 2019).

Given this reality, some educators have begun talking about these events in schools, while others feel uncertainty about its appropriateness in the classroom. Thus, as teacher educators, we felt a unique responsibility to explicitly teach, model, and practice conversations around uncomfortable topics like police brutality. In doing so, we hoped that when our students became English language arts (ELA) teachers, they would be better equipped to engage in racial and critical literacy practices and push through personal discomfort and fear, ultimately applying these strategies for the betterment of their future ELA students. Critical literacy, here, is defined as an overtly social justice oriented approach to teaching and learning that asks students to analyze and critique the sociocultural, historical, and racial systems, norms, and practices found in our everyday world that are communicated through the content of the curriculum or texts (Luke, 2004).

In our college young adult (YA) literature courses, we used the novel All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely (2015) as a starting point to talk about issues of racism and police violence against Black and Brown people. While the novel prompts conversations by itself, teacher educators have the power to shape these discussions by helping students think critically about institutional racism. Therefore, we began with the stance that dialogue supports learning (Wegerif, 2011).

Research has documented that classroom discussions about race help build relationships across difference and understanding about how society is racialized (Brown et al., 2017) and that racism is systemic (Sealey-Ruiz, 2011). Cruz-Janzen (2000) asserted, “Changes can happen with people talking face to face with each other” (p. 94), but what about when people are engaged in digitally mediated discussions? Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate how the use of technology affects the types and content of responses, especially around topics of equity, racism, and injustice.

With this purpose in mind, we examined how 24 students enrolled in two YA literature courses at primarily White universities across the United States used Flipgrid, a digitally mediated conversation tool, to critically discuss cultural and political vignettes that focused on racialized events related to the novel All American Boys. These events are not only fictional but also occur in the real world.

Flipgrid is a relatively new web-based platform and a mobile application that is designed for students to record short asynchronous conversations or presentations that include video and audio. In 2021, the option to include written comments was added. It was developed by Dr. Charles Miller at the University of Minnesota in 2014 (Grayson, 2018). In 2018, Microsoft acquired Flipgrid and made the platform free for all educators (Young, 2018), thereby “empowering every learner to share their voice” (Flipgrid, 2018). According to its website (https://flipgrid.com), Flipgrid is in over 180 countries and used by millions of pre-K to PhD teachers, students, and families.

Flipgrid has two key features: grids and topics. A grid represents a course; it is what teachers use to organize topics for their classes. A topic is Flipgrid’s term for discussion, which is where students can record multiple video responses that are threaded. When teachers create a new topic (i.e., video discussion thread), students can upload a video they have previously created and stored on their laptops, or they can record audio and video through their computers or mobile devices at that moment. Students can also add digital stickers to their videos to express personality. Behind the scenes, teacher accounts can see how many times videos have been viewed and who has responded to whom. They can also grade and give feedback to students.

The real benefit of Flipgrid as a digital discussion tool is the addition of video. Adding video to digital discussion has been shown to increase students’ social presence more than written forums (Clark et al., 2015; Lowenthal & Moore, 2020), reduce students’ feelings of isolation and increase feelings of community (Bartlett, 2018; Stoszkowski, 2018), and increase students’ engagement with content and others (Green & Green, 2018; Johnson & Skarphol, 2018; Kieper et al., 2020).

Although anecdotally Kajder (2017) lauded Flipgrid as a literacy tool for advocacy and change in that a “grid becomes a text that can persuade, invite, and excite” (para. 10) a wider audience “beyond our schools, communities of practice, and shared echo chamber” (para. 7), empirical research on Flipgrid in schools and teacher education is scarce for any purpose, let alone for social justice tasks. Studies of Flipgrid thus far have been limited to its use in language classes (Mango, 2019), engineering classes (Miskam & Saidalvi, 2019), undergraduate agribusiness law courses (Hall, 2015), public speaking courses (Gerbensky-Kerber, 2017), educational technology graduate courses (Lowenthal & Moore, 2020), and makerspace activities (Oliver et al., 2020).

In the research described in this article, we looked specifically at the following research questions: (a) How does Flipgrid mediate critical literacy practices when discussing racial injustice? and (b) What discursive moves do participants make to enact critical racial literacy? In the next section, the study is situated in relation to scholarship around ELA teacher education, race discussions, and technology.

Mediating Race Talk in the ELA Classroom

The U.S. professional organization standards for ELA teachers articulates the moral and ethical obligation of teacher educators to foreground social justice in teaching and assessing dispositions for preservice teachers in secondary ELA. Standard IV Element 1 reads, “Candidates plan and implement English language arts and literacy instruction that promotes social justice and critical engagement with complex issues related to maintaining a diverse, inclusive, equitable society” (National Council of Teachers of English & National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education, 2012). This standard creates a paradigm for thinking about injustices in society that are rooted in and responsive to individuals’ local, national and international histories and identities inclusive of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc. (Alsup & Miller, 2014). It also helps frame and rationalize critical engagements with difficult and complex topics, like racial injustice, that teachers should address in ELA texts and curricula in authentic ways.

While theories about discussing racism in the classroom abound, practice within the US has been described as difficult (Borsheim-Black, 2015; Thomas, 2015). Part of the issue is the predominant whiteness of teacher educators — authors included — and preservice teachers, alike (Matias & Grosland, 2016; Ohito, 2020). One promising model of dialogic exchange to teach critical racial literacy in classrooms is ideological dilemmas. Educators have used dilemmas in a variety of ways to theorize problems related to multiple dimensions of life, teaching, and learning in ELA.

According to Pollock (2004) and Thomas (2013, 2015), dilemmas are endemic to “race talk,” or discussions in which race is centralized. Further, Orzulak (2015) examined the ideological dilemmas preservice teachers face when confronting linguistic heterogeneity in classrooms with students from diverse backgrounds. Additionally, Fransson and Gannäs (2013) have explored how dilemmatic spaces are key to teacher learning and growth.

One type of dilemma strategy that works well with reading texts in ELA classrooms is a cultural and political vignette (CPV; Darvin, 2009, 2011, 2015, 2018). Darvin (2009) introduced CPV as a pedagogical approach in teacher education to promote critical literacy instruction and engage in conversations involving sensitive, dilemmatic social topics in secondary humanities classes. Students and educators have been receptive of vignettes as a teaching tool in both brick-and-mortar and digital classroom spaces (Hernandez-Serrano & Jonassen, 2003; Shulman, 1992; Tettegah, 2002, 2005; Whitcomb, 2002). In fact, Darvin’s (2011) findings suggest that experiencing CPVs in a teacher education course helped prepare teachers to engage in critical conversations in their own classrooms.

Building on this research-base of using vignettes to talk about cultural and political issues, we hypothesized that vignettes would provide an avenue for talking about race with preservice teachers. In addition, we hypothesized that given our predominantly White institutions, digitally mediated conversations could help open our discussions to include more diverse voices inclusive of race, geographical location, age, gender, and degree level.

Digitally Mediated Critical Conversations With Preservice ELA Teachers

Sleeter and Tettegah (2002) have contended for almost 20 years that technology is a useful and productive tool for educators and students to process and promote critical thinking and social justice especially related to multicultural education aims. By using technology, they argued, people of different and diverse backgrounds can form communities of practice through dialogue across spaces and places.

Research shows that digital tools can mediate preservice teachers’ (PSTs) dialogic learning by providing a student-centered platform to discuss race (Christian & Zippay, 2012; Matias & Grosland, 2016) and literature (Akers, 2009). Tettegah (2002), for example, argued that conversations can be emancipatory in that “by engaging in conversations about multicultural, intercultural and cross-cultural teaching practices [digitally] … teachers can learn to be critical and reflective of their own teaching and learning processes” (p. 29). Furthermore, digital conversations may be particularly helpful for students who feel marginalized in face-to-face classrooms (Wade & Fauske, 2004).

Scholarship that focuses specifically on ELA PSTs’ digital conversations of race include Groenke and Maples (2008, 2009), Kajder (2018), and Moreillon and Tatarchuk (2003). In Moreillon and Tatarchuk’s study, PSTs discussed social and cultural connections to YA literature through conversation with PSTs in another state. The PSTs in the study saw the digital conversation across states as a means to introduce differing perspectives into the classroom. The authors also reported that the conversation provided an opportunity for PSTs to begin distancing, a process of reflecting from a different vantage point, because the digital nature gave the PSTs time to consider and reconsider their remarks before commenting. This effect is particularly true of asynchronous discussions. For example, Bonk et al. (1998) found that, although synchronous discussions generated a lot of content, students in asynchronous discussions challenged and encouraged each other during extended peer interactions and dialogue more often.

Research on using digital conversations reveals tensions, however, when using technology to talk about critical sociopolitical issues. Two tensions that relate to classroom conversations are privacy and community-building. When using social media with a public audience, teacher educators can model using authentic audiences for student writing. However, when coupled with controversial issues, research has shown that PSTs’ Twitter conversations about social and political issues were more shallow than in-person conversations (Cook & Bissonnette, 2016), perhaps because they felt uneasy sharing their convictions publicly (Kruger-Ross, 2013; Van Manen, 2010). In contrast, Tettegah (2005) found that technology allowed for deeper insights than in-person discussions, where embarrassment, fear, or anger can interfere with dialogue about culture-related and social justice topics.

Allowing students to post anonymously does not seem to help resolve issues of uneasiness, according to research conducted by Landers and Callan (2014), because anonymity can deter community building. Related to community building, other studies found that written conversations do not provide visual cues or intonation, which can make building trust and building community more difficult (Bomberger, 2004; Ferdig & Roehler, 2003). This scholarship focused on written discussion forums, emails, or blogs, where multimodal forms of communication were not present.

Research on video discussions in undergraduate and graduate courses, however, shows promise for enhancing community in online spaces. Borup et al.’s (2012) study of PSTs across three courses that integrated asynchronous video in different ways found that video allowed participants to seem more real to each other and observe more emotional expression. Research on VoiceThread as a medium for discussion in higher education has found that participants perceived that video and audio components enhanced emotional connections (Parise, 2015) and increased sense of community (Kirby & Hulan 2016; Koricich 2013).

Delmas’ (2017) study with preservice teachers in both blended and online courses corroborated that the video and audio features in VoiceThread helped participants sense stronger connections with peers. Borup et al. (2012) also found that video did not solve one issue related to digital conversations. Participants reported that they could not tell if their peers were listening, unlike in face-to-face discussions.

Flipgrid is a tool that displays the number of views and allows for threaded conversations. To date, few empirical studies have examined the affordance and constraints of Flipgrid as a teaching tool or digitally mediated conversation tool, in general, and none in literacy teacher education. Due to this lack of scholarship, we were particularly interested in Flipgrid for our conversation because it provided a student-centered platform, the postings were not anonymous, and the space could be private to the participants while simultaneously allowing connections to other classes. Our study purposefully addressed this gap and examined Flipgrid as a digital mediation tool in the context of teaching critical racial literacy in an ELA education course.

Theoretical Framework

Our theoretical framework is grounded in mediated contact and critical discourse studies that take into account racial literacy formation. These theories guided our study as we examined the discursive and critical literacy moves PSTs applied during Flipgrid discussions of racial injustice during our shared reading of All American Boys. By discursive moves, we refer to ways people use language to coconstruct knowledge; by critical literacy moves, we refer to the uptake of the stances described later in the theoretical framework.

Mediated Contact

Mediated contact research explores the explicit and implicit attitudes as well as physiological responses of people when presented with culturally different others indirectly. For example, when a person of one racial identity reads a novel about a person from a different racial identity, the book mediates the contact between the real and fictional people. Research has shown that mediated contact can improve affective, cognitive, and social outcomes. Affective outcomes include empathy building, and cognitive outcomes include increased perspective-taking capacity.

Mediated contact can help promote empathy and perspective taking because of the perceived distance between the people in contact. Mar and Oatley (2008) stated that mediated contact allows “sufficient psychological distance and feelings of control to promote true empathy and perspective-taking. Direct contact may be experienced as too threatening or otherwise emotionally arousing for a great deal of empathy or even sympathy to take place” (p. 181).

Scheff (1979) called the ideal stance for learning the “optimal aesthetic distance,” which is neither too close and emotionally overwhelming nor over-distanced and indifferent. Learning about cultural and political issues through mediated contact with others provides a type of experiential social learning (Satterfield & Slovic, 2004). As such, contact with others in a digitally mediated way could also afford “optimal aesthetic distance” from which to discuss cultural and political issues such as racial injustice and police brutality.

Similar to Scheff’s (1979) notion of optimal aesthetic distance is Silverstone’s (2003) concept of “proper distance” as an ideal and moral cosmopolitan construct for communicating across difference. To understand this term, Silverstone argued that one must understand both words: proper and distance. Distance, accordingly, is “not just a material, a geographical or even a social category, but … a moral category” (p. 7). Thus, mediated spaces can create either proper or improper distance, depending on whether those communicating are willing to “imagine the other in his or her own terms” (Chouliaraki & Orgrad, 2011, p. 341).

Even when, physically and geographically speaking, people may be at a distance in cyberspaces, a so-called proper distance requires simultaneous close proximity – or what Silverstone (2003) called “recognition” and “responsibility,” when one is confronted with either familiar or novel representations and ideas. Once a person no longer feels responsible in a digitally mediated space, proximity and, therefore, proper distance is eroded. It becomes improper distance, prompting a failure of communication in which people may be objectified or othered or they may privilege dominant, majority voices over those who are in the minority or oppressed (Bauman, 1989; Chouliaraki, 2011).

Hull and Stornaiuolo (2014) extended this work on proper distance to the field of literacy, foregrounding “the cognitive, emotional, ethical, and aesthetic meaning-making capacities and practices of authors and audiences as they take differently situated others into account” (p. 17). Discursively, people negotiate moral, ideological and physical distances as they attempt to respect difference and acknowledge the unique vantage points of individuals and communities in digitally networked spaces (Stornaiuolo et al., 2018). Thus, our study investigated Flipgrid as a digital tool to mediate proper distance when engaging in critical discussions about racial injustice in the ELA education classroom.

Critical Discourse Studies

Critical discourse studies is an umbrella term that encompasses critical literacy and critical discourse analysis, as well as other theories tangential to this study, such as multiliteracies and critical language analysis (Rogers, 2018). From a critical discourse studies view, literacy is seen as a social practice that is situated in a particular cultural, political, and historical event. As Gee (2001) said,

A Discourse-based, situated, and sociocultural view of literacy demands that we see reading (and writing and speaking) as not one thing, but many: many different socioculturally situated reading (writing, speaking) practices. It demands that we see meaning in the world and in texts as situated in learners’ experiences — experiences which, if they are to be useful, must give rise to midlevel situated meanings through which learners can recognize and act on the world in specific ways. (p. 128)

Following this line of reasoning, critical literacy is a practice that deconstructs the word and the world (Freire, 1985) and empowers learners with actions that can be taken to construct a better world (Rogers, 2018).

Our view of critical literacy is rooted in Paulo Freire’s work that asks learners to engage in critical empathy, inquiry, and reflexivity while reading, writing, speaking, listening, and thinking about sociopolitical issues (Luke, 2012; McLaughlin & DeVoogd, 2004; Mirra, 2018; Scherff, 2012). Critical literacy requires a deconstruction of the status quo and reconstruction of political consciousness (Luke, 2012; Shor, 1999). This deconstruction and reconstruction is particularly relevant when addressing and developing racial literacy skills.

Sealey-Ruiz (2011) defined racial literacy as “a skill and practice in which students probe the existence of racism, and examine the effects of race and other social constructs and institutionalized systems which affect their lived experiences and representation in U.S. society” (p. 25). The goal of such racial literacy work is to help dominant racial groups adopt antiracist stances and for nondominant groups to resist victim stances.

According to Sealey-Ruiz (2011), in her course she found that in the process of becoming racially literate, students moved through and between four recursive phases as they attempted to overcome their racist beliefs, discuss race and racism, and embrace what it meant to become antiracist. These phases included (a) engaging; (b) expanding; (c) disengaging; and (d) reconnecting themselves to the pursuit of antiracism through taking responsibility to act. These phases, for the most part, align with Lewison et al.’s (2015) four dimensions of critical literacy, which include (a) consciously engaging; (b) taking responsibility to inquire; (c) entertaining alternate ways of being; and (d) being reflexive/taking action. These two frameworks work well in combination to form an understanding of a critical racial literacy. Table 1 describes these two frameworks and illustrates how they overlap.

Table 1

Combining Critical Literacy and Racial Literacy Frameworks

| Critical Literacy Dimensions (Lewison, Leland, & Harste, 2015) [a] | Racial Literacy Phases (Sealy-Ruiz, 2011) [b] |

|---|---|

| Consciously Engaging: Going beyond just answering the question to examine power relationships; recognizing how we support or disrupt the status quo; understanding that there is a choice in interpretation and response. | Engaging: A desire to read literature to better understand others lived experiences; Expressing emotions such as resistance, shame, interest or guilt in new ideas, concepts that emerge in relation to one’s own identity. |

| Taking Responsibility to Inquire: Gaining knowledge from multiple perspectives; creating new questions with new knowledge; reframing of school through critical questioning | |

| Entertaining Alternative Ways of Being: Using tension to examine what isn’t working; taking on new discourses or perspectives. | Expanding: A time of discovery and racial epiphanies especially as it relates to complicity in racist and biased thought and actions and the perpetuation of stereotypes; developing more nuanced views of race and racism. |

| Disengaging: a waning interest in the literature that was exciting before; resistance to talking about race and racism; feeling overwhelmed by the accumulation of newfound knowledge and a desire to take a break. | |

| Being Reflexive/Taking Action: Being aware of own complicity in keeping status quo; retheorizing of own beliefs; using discussion to grow; engaging in praxis. | Reconnecting: A desire to do the work; a sense of responsibility to take action |

| [a] These can occur simultaneously and are nonlinear. | [b] These can be recursive but are linear. |

At its foundation, critical literacy, and thus racial literacy, happens through “dialogic exchange” (Luke, 2012, p. 7). It is not knowledge that can be deposited into a person’s head nor a finite set of skills that can be mastered in one course. It is a continual process over time. As Putnam and Borko (2000) stated, “When diverse groups of teachers with different types of knowledge and expertise come together in discourse communities, community members can draw upon and incorporate each other’s expertise to create rich conversations and new insights into teaching and learning” (p. 8).

In Sealey-Ruiz’s (2011, 2013) semester-long study on the development of racial literacy skills of freshmen in a community college composition course, for example, students began to deconstruct and actively challenge stereotypes about Blacks and other racialized minorities through their writing and discussions. Thus, critical racial literacy is continually formed, updated, and revised as people interact with and integrate cultural, political, social, and historical texts and dialogic exchanges with people from multiple perspectives as they interrogate their own lines of inquiry.

Additionally, critical racial literacy recognizes that race, as a signifier, is discursively constructed through language (Hall, 1996) and is fluid, unstable, and socially constructed rather than static (Omi & Winant, 1986). Critical discourse analysis then, acknowledges that language is a social practice that is tied to power dynamics. When using critical discourse as a lens, the content, form, and function of language are linked to political relationships between speakers/writers and listeners/readers (Gee, 2011; Rogers, 2011).

In analysis, the content of language, such as word choice, is investigated as well as the form and function of language, such as genre. According to Fairclough (1993), genre refers to “the use of language associated with a particular social activity” and is a form known to members of a discourse group (p. 138). In our study, the genre under investigation was discussion boards. The students were familiar with posting an original response to the instructor’s prompt and then commenting on other students’ posts. However, unlike traditional discussion boards that make use only of text, our discussion boards used video, via the app Flipgrid.

Research Design

This exploratory qualitative study used a collective case study method (Stake, 1995). The study was bounded by students in two YA literature classes, and data were analyzed for patterns collectively. We focused on ways participants used critical literacy in Flipgrid while discussing racial injustices depicted in All American Boys. The impetus for using Flipgrid was to expand our students’ perspectives and views on racialized topics beyond their local, geographic knowledge and beliefs, which were limited by the insularity of the cohort model, sometimes called the “cohort effect” (Ferdig & Roehler, 2003).

Participants

Participants were recruited from two YA literature courses during the period of one semester at two universities located in Midwest and Southeast U.S. As seen in Table 2, 24 students agreed to participate. The majority were undergraduates (n = 19) and preservice teachers (n = 21) working toward initial licensure for secondary teaching. Students at the southeastern university were a cohort and, thus, took all classes together during their final 2 years in the program.

Table 2

Participant Demographics

| Professional Experience and Demographics | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Years of Teaching Experience | |

| 0 | 21 |

| 1-2 | 3 |

| Education Level | |

| Bachelors | 19 |

| Masters | 3 |

| Doctorate | 2 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 2 |

| Female | 22 |

| Ethnoracial Identity | |

| African-American | 2 |

| Hispanic | 1 |

| Middle Eastern | 1 |

| White | 21 |

Positionality

Althouh we come from different socio-economic backgrounds, as White, cisgendered, temporarily able-bodied, heterosexual females, we understand the privilege that comes with most of our identity categories. We both continuously reflect on our own White privilege, are committed to antiracist education, and actively work toward dismantling White supremacy through our own reading and learning so as to model allyship and activism in our schools and communities.

As instructors of the courses under investigation, we acknowledge the power relationship between the participants and ourselves as their professors. As such, we followed ethical protocols approved by our research boards and remained critically reflexive throughout the study.

Curriculum Design

The YA novel, All American Boys by Reynolds and Kiely (2015), was the anchor text on which both YA courses focused for this study. This text was chosen for our classes because at the time of the study acts of police brutality and racism were prevalent and constantly making the news. All American Boys provided a unique framing by offering two perspectives (a White and a Black perspective), which we felt would lend itself to deep and meaningful discussion for potential future teachers. In All American Boys, one narrator is Rashad, an African American teenager who becomes a victim of police brutality, and the second narrator is Quinn, a White teenager who witnesses the violence.

Activities Before and During Reading

In conjunction with reading All American Boys, students participated in reader response activities and discussions using both traditional methods – text annotation, reflections, and whole-class conversations – and digital tools – blogs, vlogs, polls, VoiceThreads, and Padlets. Course activities took place both inside and outside of face-to-face class meetings.

Before reading All American Boys, both authors spoke with their respective class about the upcoming topic, why we felt it was important to study in class, and possible triggers that might occur. Students participated in an anticipation guide about race, viewed the Guardian’s The Counted webpage (https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/series/counted-us-police-killings/all), and watched Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche’s TED Talk titled The Danger of a Single Story.

While reading the novel, students were prompted to respond on their course blog, read all classmates’ posts, and comment on at least two threads. Additionally, we discussed current racialized events – some of which occurred only a few counties away or on our own campuses. Our discussion of this book and the issues it presented lasted several weeks.

Cultural and Political Vignettes and Flipgrid

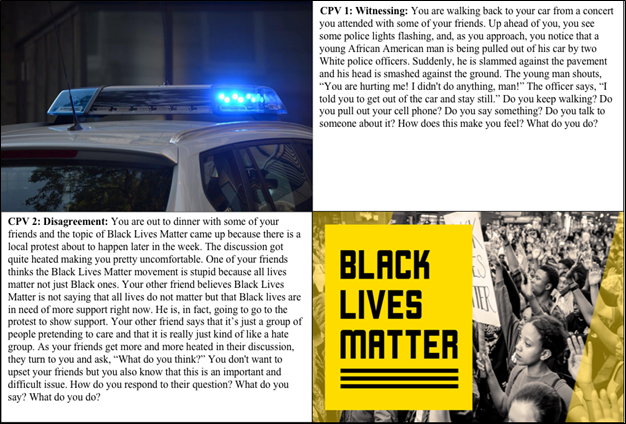

After reading, students participated in a conversation across the two universities using a protocol called CPVs (Darvin, 2009). We used this framework with both of our YA literature courses, not only for the reading of All American Boys, but throughout the semester as a way to think about teaching and discussing tough topics found in literature and life. The plot of All American Boys offered many potential scenarios on which students could reflect on their assumptions, biases, and potential actions. Figure 1 shows two CPVs used for student discussion across two courses.

Figure 1

Cultural and Political Vignette (CPV) Prompts

Using this CPV framework, we gave students realistic, open-ended, and potentially controversial vignettes/scenarios and asked them to contemplate what they would do in that situation and respond through video on Flipgrid. Flipgrid is a discussion forum with private (not open to the general public) and public (open for anyone to respond) settings, where participants post a response by uploading a video. The Flipgrid discussions under investigation were password-protected and asynchronous across students in both universities. Flipgrid, as a conversation tool, provided a closed space to protect students’ privacy and provided a multimodal response format to promote community-building and exchange of ideas within and across campuses.

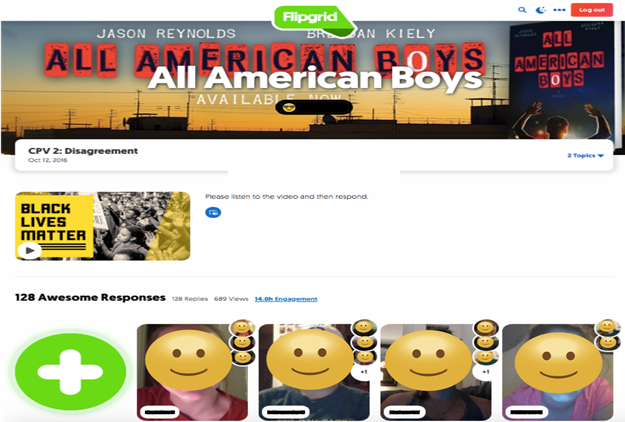

Students responded to CPV prompts through videos, and then watched each other’s videos to garner diverse perspectives. Students replied via video to critique or build upon others’ ideas. Each class then met face-to-face and continued discussions. Figure 2 is a screenshot of one CPV grid on Flipgrid from the student perspective. We added smiley faces to protect participants’ identities.

Figure 2

All American Boys CPV 2 Flipgrid from the Student Perspective

Data Collection

This data set comes from a larger study that explored how PSTs discussed race, police violence, and injustice through YA literature. For this article, though, we zoomed in on one particular aspect of the study: students’ use of language, critical racial literacy, and discursive moves when discussing CPVs about racial dilemmas through Flipgrid. In total, 305 short videos (48 initial video posts and 257 reply posts) were collected from Flipgrid. The content was transcribed for analysis.

In addition to initial posts, students were asked to reply to at least 10 videos across two CPVs. Video posts and responses ranged from 30 to 90 seconds in length. (At the time of this study, Flipgrid only allowed a maximum of 1.5 minutes per video. Currently, Flipgrid videos can be up to 5 minutes in length.) In total, students viewed videos 1,328 times and logged 27 hours of engagement with CPV videos, according to Flipgrid’s analytics.

Along with Flipgrid, we also conducted follow-up face-to-face, semiformal interviews with eight participants (four from each university course), which were audiorecorded and transcribed. Students were chosen based on (a) a representative range of opinions we saw in the Flipgrid discussions, (b) interest, and (c) availability. The aim was to capture additional insights about using the CPV framework and a digital mediated tool to discuss topics of race, injustice, and police brutality.

Data Analysis

Throughout the process, we analyzed data using a hybrid analysis approach of thematic (Boyatzis, 1998) and critical discourse analysis (Rogers, 2011). Critical discourse guided our analysis as we examined the digitally mediated discussions of racism and police relations while students read All American Boys. Keeping our research questions in mind, first both researchers coded data a priori independently. The a priori codes consisted of Lewison et al’s (2015) four critical literacy dimensions as they related to Sealey-Ruiz’s (2011) racial literacy phases (e.g., passive responses relates to Phase 3 of disengaging).

After coding 10% of the data, we discussed coding and worked through any differences of interpretation until we reached consensus. We then independently coded the rest of the data using the a priori codes (indicated by note [a] in Table 3). In addition, several other code categories emerged through inductive coding (e.g., text, world, and personal connections). A graduate research assistant acted as a third set of eyes, also known as employing investigator triangulation (Patton, 1999), to enhance the quality and credibility of the initial coding and to reduce potential bias. This first round of coding served to reduce the data into a manageable set for deeper analysis.

Table 3

Coding Scheme, Examples, and Frequency of Codes

| Code | Quote Example | CPV 1 No. of Codes | CPV 2 No. of Codes | Total No. of Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consciously Engaging [a] | “I don't know if I'd have the courage or even just the thought to pull out my phone and start recording but hopefully discussing these scenarios will help me be better prepared if I ever do come upon something like that.” | 34 | 34 | 68 |

| Entertaining Alternative Ways of Being [a] | “I think a lot of the reason people don't understand it because they don't want to understand and they don't see it happening in their own lives or in the lives of people around them so they don't want to admit there's an issue because they don't have to deal with that issue.” | 14 | 17 | 31 |

| Taking Responsibility to Inquire [a] | “I also like how you asked question you would ask questions to the people they're talking and saying these things just so that you can further understand what they're trying to say and where they're coming from because if you don't understand that then the conversation will just get out of hand.” | 12 | 23 | 35 |

| Being Reflexive [a] | “I think it's good that you challenge them. I definitely want to do that and do that now with all of my friends and with my own belief systems.” | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| Passive Responses | “I just don't really like giving my opinion on controversial issues because I don't want to offend.” | 27 | 3 | 30 |

| Personal Connections | “I lived in New York for a while and you know walking down the street if there was something happening and there were like a group like a couple of people just stopping and witnessing whatever was happening other people who are walking down the street also just like stop for a second right.” | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| World Connections | “Look at another activist group --say for endangered species, save the polar bears. They're not saying that all other bears should be forgotten about and they're just saying that the polar bears need more attention right now, and I think that's the same thing that the Black Lives Matter movement is trying to say.” | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| Text Connections | “Like just in the book All American Boys like Quinn didn't do anything when he saw it happening and it kind of replayed over and over his head and he didn't want to watch the video he kind of wanted to ignore it happening and it drove him nuts.” | 11 | 2 | 13 |

| [a] Indicates independently coded data using a priori codes. | ||||

For the second round, we openly coded the critical racial literacy moves, looking at what was said (i.e., content), how it was said (i.e., form and function), as well as nonverbal cues (Erickson, 2006). From there, we identified “rich points” in the data to reduce the data further. Agar (2004) described rich points as places “the researcher looks for surprising occurrences in language, problems in understanding that need to be pursued” (p. 94). These rich points then were analyzed for patterns regarding function and content of the discursive moves to examine participants’ “positions or perspectives” (Fairclough, 2013, p. 182). Giroux’s (2006) advice to look for both “critique” and “possibility” guided our analysis as it related to critical racial literacy.

Findings

Throughout the digitally mediated discussions on Flipgrid using the CPV protocol, PSTs demonstrated language use to build solidarity with peers and language that challenged their peers’ responses in relation to race topics. The strongest patterns related to challenging peers. Three themes are described in this section: movement toward challenging peers, challenging through questioning, and challenging through reflecting on racial bias.

Movement Toward Challenging Peers

As PSTs discussed the CPVs, they began to entertain alternate ways of being (as described in Lewison et al., 2015). One of the affordances of Flipgrid was that we could open the walls of the classroom and discuss with new people. Chloe (pseudonym), an undergraduate, stated in the interview,

Having other people’s perspectives made it a lot more beneficial to me personally. Because we hear each other [in the cohort] every day. When we got to communicate and talk to people who we’ve never met before about something that’s, like, so real, there definitely was a take-away.

By talking with new people, Chloe believed that she was able to hear different perspectives about racial injustices and that entertaining these new perspectives was beneficial to her understanding of the real life issues, issues she had not experienced firsthand due to her own White privilege. She said,

It’s hard for me to relate to a lot of these things [social justice issues], because I’m a White female, whatever. And then you have people who come in, they go through crazy stuff. You think you have it bad. And you don’t really.… That definitely made me not jump to conclusions about that stuff [policing] anymore. I definitely want to hear both sides.

Hearing other people’s experiences gave Chloe a sense of proximity to social inequalities in the world. Through sharing ideas on Flipgrid, Chloe achieved Sheff’s (1979) optimal aesthetic distance, in that she was able then to engage in the issues by consciously seeking out alternative stories to the narrative she had listened to her “entire life.” She said that “being around people who have experiences makes it more personal. Because it’s like, ‘Wow. This does go on.’ When you’re not exposed to it, you don’t know.”

Marie, a graduate student who also identified as a White female, shared a similar story and added that becoming a teacher who would be working with students of color motivated her to consciously engage (as also in Lewison et al., 2015; Sealey-Ruiz, 2011) in reading All American Boys and discuss racism and other social issues with classmates.

I didn’t know anything, really, about it [police brutality], and I honestly, I think, had the privilege of not really looking that much up about it…. So, now that I’m studying to be a teacher, and we were talking about social issues in the classroom, and I’m going to be working with more minority students, where they don’t have the luxury of not knowing about it, I was more interested in it.

Marie also felt that hearing other points of view was an added benefit of the Flipgrid discussions involving the other class, sentiments echoed in undergraduate interviews as well. Lauryn said, “It was nice to have a different perspective. There was one guy in our class. Yeah, so it’s cool to have [more] guys’ perspectives.” In these ways, Flipgrid served as a mediator for participants to engage with people who held a different point of view or identity from them, echoing Mar and Oatley’s (2008) research on empathy.

In addition, we observed participants moving from neutral stances toward challenging peers during the CPV discussions between universities on Flipgrid. Marie described herself as “nonconfrontational” and found the Flipgrid platform conducive to having “productive conversations.” She stated in the interviews that the asynchronous video discussions provided the right “balance” of personal – having the person’s face and voice – with proper distance (as also in Silverston, 2003) – having the time to think through what to say. She said,

Since we were kind of a step removed – because it wasn’t a live discussion, it was taped responses – I was able to kind of evaluate each of their points and respond respectfully, which is the goal in real life, as well, but more of a challenge when emotions are immediately involved.

This sentiment echoes Bonk et al.’s (1998) finding that asynchronous discussions allowed for more critical reflective thought. She went on to say that she chose to respond to videos that were different from her point of view, something she did not necessarily feel comfortable doing in large, in-person class discussions (see Tettegah, 2005).

Emotions and different points of view were, in fact, part of CPV Scenario 2 in Flipgrid (see Figure 1). Students were given a prompt regarding a heated discussion with friends about Black Lives Matter. Figure 3 depicts one thread from that discussion. Alicia was a Black graduate student who had studied the Black Lives Matter movement in other coursework. Her brave response contrasts the previous posts she viewed on Flipgrid by saying she wouldn’t be “so neutral.” We interpreted this statement as implying that she felt the previous posters were giving politically neutral responses.

Two undergraduates replied to Alicia’s response. One said he appreciated that Alicia was not neutral, even though he considered himself a neutral person, which indicated a move from his first statement when he seemed to view neutrality as the ideal stance: “Not taking a side is a good way to go in that particular situation where tensions are running high.” In the second reply, by Kamden, she admitted that Alicia’s post helped her think differently.

The example is one of several in which PSTs indicated a shift in mindset from neutral to consciously engaging (Lewison et al., 2015; Sealey-Ruiz, 2011) on issues of race and racism during the Flipgrid CPV discussions. To be clear about our data, indications of this movement happened in less than 10% of the Flipgrid comments (see Falter & Kerkhoff, 2018 for patterns related to the 90%). We chose to zoom in on these glimpses of movement to shine light on both critique and possibility (Giroux, 2006), the intent stated in our methods.

Figure 3

Transcript 1 From CPV 2 Discussion

| ALICIA’S CPV POST (graduate): So in this conversation regarding Black Lives Matter I'm with my friends, you know, I don't think I'd be so neutral to the all lives matter person. And I would say, okay, all lives matter, but the reality is that tends to be in principle only and not in practice, right? So all lives matter people aren't doing anything, They just say it as a response to Black lives matter when in reality if you believe all lives matter you should be behind Black lives matter. You should be behind Latino lives matters; you should be behind trans lives matter; you should be behind people advocating for their own humanity. But when a non-black person is brutalized, you know, by the cops, it's not all lives matter people showing up. It's Black lives matter because they're doing the work, they're organizing, they're trying to reform our system, and that's how I would address that. To the person who thought it was a hate group, um, I would just ask what is it about the organizational mission, their literature, their manifesto that supports that claim. I feel like you know that can be disproven very easily by just like we're looking at what the organization says about their mission um and then I would support the person was going and I would say you know I would challenge us all to go, there is safety in numbers and that way we get to hear it straight from the people organizing in the local chapter of the you get a firsthand account of what the organization is trying to do and we can continue to further the conversation. |

| FORREST’S COMMENT (undergraduate): Hi there. I appreciate what you said and for taking a side because I feel like most people are more neutral in these discussions myself included and I really like what you said to the all lives matter friend that if all lives matter then there should not be an issue with black lives matter and so I really like what you had to say about that. I'm not sure on how that would help with the tension in the room but they ask for your opinion and you gave your opinion and I think that's good and I certainly appreciate that. I think that it is important to realize that all lives matter people sign that has come out in response to people saying that black lives matter and while it's true that all lives matter, you can't say that without recognizing that black lives matter as well. |

| KAMDYN’S COMMENT (undergraduate): Alicia, I never really thought about it in the way that you just put it and I agree with you one hundred percent. If you are advocating that all lives matter, if you really believe that, then you should be advocating for black lives matter and that lets you know that lives matter and that the LGBTQ community lives matters as well and you have to put that in practice. You can't just say things, I mean you can, but that doesn't really give you any credibility to your point and I think it's so important in the situation that you make that very clear in a respectful way obviously. I've talked about in some of my other responses that it has to be a respectful tone and you have to keep calm. |

When asked in the interviews about the possibility of Flipgrid to mediate difficult conversations, two participants said that they felt uncomfortable revealing their true convictions, either because of the online nature (according to one graduate student) or because of talking with people that they did not know (one undergraduate). However, six out of the eight interviewees felt that an affordance of Flipgrid was that participants would be “honest” and “legit” because one’s face and name were attached to the video and because the videos required a concise statement forcing one to get to the essence of what one believes.

Our participants’ responses corroborated Landers and Callan’s (2014) findings that anonymity makes participants less likely to buy into discussions. Additionally, these insights further the notion that a proper distance was achieved for at least our six interviewees, in that there was an “ethical commitment” (Hull & Stornaiuolo, 2014) toward meaning-making across differences. Similarly, we noticed that across our classes, participants shared convictions on Flipgrid and even challenged each other by sharing different views than previous posters did. The example in Figure 4 showed Alicia indirectly challenging other students (those from the other university) by using the word “neutral,” which she heard in previous video responses, and then offered a different perspective. In addition to offering differing perspectives indirectly, participants challenged peers’ perspectives by asking questions.

Challenging Through Questioning

Participants used the critical stance of taking responsibility to inquire (Lewison et al., 2015) to virtually challenge the hypothetical peers in the CPV 2 dinner scenario by asking questions. Many participants stated in their original video that they would ask questions to the hypothetical friend at the dinner party who said that Black Lives Matter is a hate group. They indicated that they would ask (a) where their beliefs came from, (b) what the person’s definition of a hate group was, (c) what the person believed was the mission of Black Lives Matter, and (d) what their evidence was.

Chad, a White male graduate student, began his response on Flipgrid with a friendly smile and related the racialized topic to his own life and what he saw on his Facebook feed. He provided a historical perspective relating All Lives Matter as a response to Black Lives Matter and then described how he would use a question to challenge the hypothetical friend who believed Black Lives Matter is a hate group: “I would ask what their evidence for this is.” In Figure 4 is the transcript of a White female undergraduate student replying to Chad, uptaking several main points of Chad’s post. She stated that she planned to use the questioning of evidence to reflect on her own positions and to challenge her friends.

Figure 4

Transcript 2 From CPV 2 Discussion

| CHAD's CPV POST (graduate): [smiles] This actually sounds like a typical Facebook post that I've seen in the past year, so to the first friend that says all lives matter it needs to be made clear that All Lives Matter as a hashtag. as a catch phrase, whatever you call it. is simply a response to Black individuals expressing care for their own lives and that all lives matter activists [sarcastic tone] if you want to call them that do nothing even when white individuals are brutalized by the police so there's no ground to stand on, no foundation for that. For the friend that calls them a hate group, urn I would ask what their evidence for this is and if the "violence" [air quotes] that’s perpetrated during protests is not in fact in reciprocation to violence perpetrated against them during what would normally be a peaceful protest. .And as for my second friend that believes that Black lives do matter and he’s going to join the protest I would congratulate them and probably text them later and tell them that they are really mv favorite friend [smiles]. |

| HAILEY’S COMMENT (undergraduate): Well. I think your responses are great. I [looks up and to side, furrows brows] didn't realize that All Lives Matter is actually just a response to Black Lives Matter, sol think that was really [pauses] a good way to put that. I think it's good that you would initially respond to your friends because like in all conversation that's what we would do in real life, not pause and say okay let me think through this before I answer [laughs] which is what I would want to do so I didn't say anything terrible. For the person who says this is a hate group, you asking them for evidence is a really good idea [raises eyebrows], I didn't think about that but that's true we as people sometimes make really blunt broad statements for a reaction or just because [shrugs shoulders] that's the first thing that comes to mind and sometimes we don't have evidence for it. so, I think it's good that you challenge them. I definitely want to do that and do that now with all of my friends and with my own belief systems. Keep challenging them. Make sure that I am saying what I have seen or is true. |

As participants listened to each other, this theme of challenging through inquiry grew as responders decided they also would take up this approach. In sum, the word “question” appeared 73 times in the Flipgrid discussion data. For example, in the Flipgrid discussion between Lauryn, Alicia, and Becky, Becky said, “I’m adding here to the chorus of agreement that your questioning of your friend about their definition of hate group and your call for them to potentially reevaluate that definition is a really important one” (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Transcript 3 From CPV 2 Discussion

| LAURYN’S COMMENT (undergraduate): For me, I would have to say that I agree with the [hypothetical] person that said that black lives matter is a movement that advocates for Black Lives Matter in just as much as other people's lives. I would say that as a black woman I support Black Lives Matter. It is about police brutality and it's not about, like, trying to make it seem like black people are trying to become superior to other groups of people. As for the [hypothetical] guy that thinks Black Lives Matter is a hate group, I think we need to re-evaluate the term hate group and if I were in a situation that I would probably have to say something to him about re-evaluating the definition of a hate group. With people advocating for equal treatment and standing up against police brutality how does that make them a hate group? I think that's what I would question with him. |

| ALICIA’s COMMENT (graduate): I said something similar in my response too about this idea of reevaluating the term hate group. I think people throw that term around so loosely, and it's really problematic. To think that what a group like Black Lives Matter is advocating for--human rights, dignity, respect, advocating against police brutality--that that somehow gets lumped into a hate group. Or people hear Black Lives Matter and automatically their brain translates Black Lives Matter to Black Lives Matter over anyone else’s life. I think that people who feel that way really need to reflect and think through why Black Lives Matter is such a threatening phrase. Why did that kind of make me think of things like hate groups? Why does that make me think of things like black supremacy? Being on the outside of that, and as someone who doesn't believe those things that it seems a little odd that these conversations even come up. Like people have tried to get Black Lives Matter categorized as a terrorist organization and I’m not really quite sure why. Right? Based on what they're doing, what they're fighting for. I definitely appreciate your point. |

| BECKY’S COMMENT (graduate): I'm adding here to the chorus of agreement that your asking of your friend about their definition of hate group and your call for them to potentially reevaluate that definition is a really important one, and I think maybe part of that reconstruction of their definition of hate group is trying to think of like who is the hate group against? And my guess would be that they would think that Black Lives Matter as being a hate group against police officers. But I think it's really important to think about, like, police officers have a lot of power in U.S. society, and so I wonder if a hate group can only be a powerful group of people or like a group of people with social power that are trying to maintain a status quo. When I think of a hate group, I immediately think of the KKK like that is the image I have in my head. That's a bunch of white people who are trying to maintain a racial status quo, so I think of power and who's holding the power and who is, you know, being violent is a really important way to help your friend reevaluate that definition. |

By challenging through questioning, the participants were building solidarity with their virtual peers by creating a shared understanding of what a hate group was and what the mission of Black Lives Matter was through participating in a community of practice (Sleeter & Tettegah, 2002), while at the same time moving the conversation in a productive and critical direction. By listening first to understand (Freire, 1970), participants found a strategy that spoke to their “inner teacher,” as two participants articulated in their responses.

Becky, in particular, noted in response to another student,

I also like how you would ask questions to the people just so that you can further understand what they’re trying to say and where they’re coming from, because if you don’t understand that, then the conversation will just get out of hand.

For the future teachers in this study, taking initiative to inquire and listening first to understand are important elements of critical literacy that were demonstrated through using CPV protocols over Flipgrid.

In addition, Lauryn, an undergraduate Black student, shared in the interviews how she had grown in her ability to challenge peers directly in a way where she would be heard. She described how she had practiced and become better at first asking people to explain what they mean and then sharing her perspective. Lauryn also shared how she took on the burden of protecting White classmates’ feelings during discussions about race in that she felt she had to be extra careful of how she expressed her thoughts.

When asked about the Flipgrid CPV specifically, Lauryn (Figure 6) said that she “responded to a few people that I thought could use my info” and that she did not respond to a person that she felt would not listen to her point of view. Then she added, “But I did notice that a Black student in the other class responded to her and put her in check.” When Lauryn said “check” here, she was referring to pointing out when a person is speaking from cultural assumptions and racial bias without knowing that it is a faulty or problematic assumption, which relates to the next finding.

Figure 6

Interview Transcript With Lauryn

| Researcher: Describe for me what you remember about the different discussions that were going on, and talk about what you were thinking about and feeling as we were talking about All American Boys. |

| Lauryn: In this type of discussion—and because our class, we're all familiar with each other; we've been with each other for the past few years—I feel like I have to say something. I can't just sit there and let people share their opinions. I have to share mine too, because not that I feel like I have to be a spokesperson for my race, but, like, for me to sit there and not say anything wouldn't feel right. So, I found myself, like, I felt like I had lot to say that day. I wanted to, like, check people, which is not necessarily a good thing, but I have to practice—and I've gotten a lot better at—just listening and responding respectfully and stuff, which I'm proud of myself for that. But yeah, that was one thing that I was aware of the entire time: making sure it wasn't calling anyone out or, like, making them feel attacked, because a lot of people in our class feel attacked just by me, like, glancing over. That thing about that. I didn't go into the discussion anxious at all; it was fine. I had no problem sharing the way I feel about something, or about a book. I don't know. What else do you want me to say? |

| Researcher: So, I want to hear more about this "checking people" thing. First of all, what do you mean when you say that? |

| Lauryn: If I hear someone say something that is not necessarily true, then I have to, like, put them in their place in a way. Just, like, ask them what they mean by that and then say, "Well, think about it this way." So, like, checking somebody could be yelling at them, like, "Oh, you're wrong," but, like, the way I would do it is, like, "Hey, like, I have a different opinion. Hear me out, and maybe it'll change your opinion," type thing. |

| Researcher: So, can you think of a particular moment when you felt like you had to check somebody during that discussion? Or a general idea of what you were checking would be? |

| Lauryn: I can't remember specifics. I kind of said this before, but after one student said that the book was painting police in a bad light, then I said, "But it didn't. Like, Rashad's dad was a police officer. You've got to see, like, friends of the police officer talking. You've got every perspective." It doesn't even have to be, like, a mean - It's just, like, you can't read my non-verbal communication. That type of thing. |

| Researcher: Right. So, you also said that you also have to watch yourself? |

| Lauryn: Yeah. I don't think I'm harsh or mean or have an attitude usually, but a lot of people are intimidated by me. And it probably is because I'm the only black person in the class; they don't want to offend me. But I find that when I say something about whatever topic, and the person disagrees, I don't know, they feel attacked no matter how I go about it. So, there's always tears or some kind of response, even if I don't do anything really. So, it's just having to make sure that I don't trigger anybody else. |

| Researcher: That's got to be a hard burden, though, I would think. |

| Lauryn: I mean, it's not terrible. I'm used to it, so... I kind of have a duty to talk about it (racism], but I feel like a teacher, especially a teacher with black students, should be doing the same thing that I'm doing. I don't really see how you could be a teacher without recognizing it and talking about it, or how you could be afraid to talk about it if you're going to be a teacher. And it's not just black people. It's any other oppressed group. If there are any negative viewpoints towards a group, you have to be aware of that and talk about it, otherwise it's going to affect your instruction and the way you come off to your students. |

Challenging Through Reflecting on Cultural Assumptions and Racial Bias

In addition to questioning peers, participants synthesized across posts to question the assumptions that appeared to be common in their peers’ responses. Participants used the critical stance of being reflexive (Lewison et al., 2015) to question these cultural assumptions in themselves, in society, and in their peers. Some students’ mentioned their own assumption that police officers were doing what is right. Other participants expanded on the idea, saying that “our” culture assumes that police officers are doing what is right.

Most of this reflexive work was indirect, meaning that the words culture, race, assumption, or bias were not necessarily used, but the seedlings of reflexivity appeared through word choice. For example, a participant used the word “we” when she talked about CPV 1 of witnessing a police officer beating a young man. She said, “We’ve been taught for our whole lives not to interfere with police business.” Her use of “we” seems to be speaking for all people without realizing that she is only speaking for her own, dominant culture and that other cultures and races may have been taught differently.

Other participants were direct: “I do think that regardless of skin color there’s a certain, like, societal norm that a civilian is submissive to a police officer.” In the following Flipgrid transcript (see Figure 7), Melanie posted that she would not do anything if she saw a police officer beating a young man. What follows are three graduate students who used the post to challenge the underlying cultural assumptions rather than challenge her personally.

As a result of the CPV discussion that challenged peers’ assumptions, an undergraduate said in Flipgrid, “I think it’s good that you challenge [people’s beliefs]. I definitely want to do that and do that now with all of my friends and with my own belief systems.” In addition to challenging one’s own and others’ assumptions and biases, this quotation brings us back to the first finding that the data showed participants’ beginning to shift to a more critical stance in CPV discussions over Flipgrid.

Figure 7

Transcript 3 From CPV 1 Discussion

| MELANIE’S CPV POST (undergraduate): I feel like this is really difficult to answer. Ultimately we want to be good people, and we want to say that we would help everyone we see in trouble. But I can honestly say I would probably try and remove myself from the situation. I don't know what went on before I got there. I don't know everyone involved's rationale or like their train of thought during this, so I would probably try and stay away from this situation as to not be hurt or associated with what could have gone wrong since I don't know what had happened. I wouldn't think to pull out my camera. I just don't actually videotape everything, but I can honestly say I probably would just keep walking unfortunately. |

| BECKY’S COMMENT (graduate): Your uncertainty about the kind of intentionality of both parties in this situation really got me thinking about how in the United States there is sort of this assumption that police officers and law enforcement more generally always have good intentions because they are entrusted to protect and serve the people that are under their jurisdiction. But I think your uncertainty actually shows that you know that assumption is not always a good one to have because there's really no way of knowing a person's motivation in these situations and a police officer can have bad intentions and someone can be mistaken for committing a crime when they're actually not, you know walking on the street while black, while other times you know there are police officers that are doing the right thing and serving in a way that is just and there are criminals on the streets of all racial backgrounds. These assumptions are actually the problem. We automatically assume that the police are doing the right thing, and that black people are not doing the right thing. So it's really important to actually think about intentionality in all of these particular kinds of situations. |

| CHAD’S COMMENT (graduate): I'd like to sort of direct my attention to the beginning of what you said and this idea that there's a necessary requirement for you to understand the entire situation that may in some way excuse excessive force used against individuals are individuals of color and I think that this is a pervasive idea that is extremely harmful to communities of color this idea that there is some degree of delinquency or illegal behavior that warrants excessive violence on the part of authorities or police officers if we see a police officer and an individual of color in an altercation and the police officer is very clearly in a position of power at that point the police officer has the opportunity to subdue this person but not to employ excessive force and I think that doesn't need to be lost in this ongoing debate about these topics. |

| ALICIA’S COMMENT (graduate): So, I think this is a very honest response. I think you're right. A lot of times you want to say this is what I would do. I would be the good person in this situation, but once we're in the moment, it's actually quite difficult. We're worried about our own safety. We've been taught and socialized to keep our head down, keep on moving, you don't interfere with you know what cops are doing, but that you just don't you don't get into other people's business, right. So if you see a fight on the street, if you see an arrest, you just try to keep yourself safe, and kind of pretend you don't see anything, keep your head down, so I definitely understand that impulse. I think you know all we can really do is challenge ourselves to continue to be better, right, and the only thing I can think of is that if I was in that situation I would want someone watching it, I would want someone paying attention even if they didn't interfere physically. I don't think I would expect that necessarily. But I wouldn't want people keeping their head down for me and so that's what I try to keep in mind in the back of my head as I think through some of these things. |

When asked if participating in the CPVs over Flipgrid helped her reflect on her racial and cultural values, political ideologies, or biases, Chloe emphatically said, “Yes. Oh my God, yes.” Marie said that the process of thinking through the hypothetical situations in the CPVs, discussing what people would do in the situation, and reflecting on what she would do in real life had an impact on her, one that she would want to replicate with her future students:

It caused me to reflect on it, and think about the fact that I would probably know that something like that was wrong and not want to deal with it, but I also, at least definitely before we read this book, wouldn’t have necessarily done anything about it…. I think that it’d be a beneficial discussion to be, like, what’s really the importance of studying it [police brutality] if it’s not going to lead to action?

Marie’s takeaway was that learning about social justice and reflection on one’s assumptions should lead to action, both personally and systemically. Reflection of her own inaction in the past through the CPV exercise led to her decision to engage in social justice now with a teacher activist stance in her own classroom and in her community. Findings from the study provide takeaways for teaching and research, which will be described in the next section.

Discussion and Implications

Returning to the research questions, Flipgrid served to mediate critical literacy practices when discussing racial injustice. At least seven participants credited the discussions taking place across universities as providing an opportunity to think about alternative viewpoints. Moreover, participants used questioning to understand others’ views and reflecting on cultural assumptions as discursive moves to challenge peers and to move conversations in a productive direction.

The findings of this study have implications for educational research and teacher education related to expanding on personal experiences by zooming in and zooming out during discussions and building solidarity within digital platforms; both of these implications will be discussed in greater depth in the following sections. These implications are not without limits. Dialogue itself is not enough to ensure racial justice. Dialogue is one dimension of preparing antiracist teachers and not an unproblematic dimension (see Falter & Kerkhoff, 2018). Discussions can trigger past trauma or introduce trauma. Or, as seen in our data, the labor in discussions about race can fall heavily on people of color. Teacher educators can actively work to minimize limitations and avoid pitfalls to build PSTs’ critical racial literacy.

Zooming In and Out

The CPV protocols asked students to put themselves in a potential real-world dilemma and to share their personal reactions, thoughts, and feelings. Although the situations were hypothetical, they were timely. At the time of the study, one group was geographically close to an African-American man being fatally shot by a police officer, making proximity a matter of nearness in space as well as time for this group. Through these hypothetical situations, participants drew from and shared their own personal and proximal experiences or lack of experience as well. Our study corroborates the research on PSTs that has found drawing on personal experience can foster new understandings about social difference (Milner, 2006; Sleeter, 2011). Sealey-Ruiz (2020) called this process an engaging in an archaeology of the self – “an action-oriented process requiring love, humility, reflection, an understanding of history, and a commitment to working against racial injustice” (n.p.)

Yet, Lewison et al. (2015) warned that, while personal experiences are certainly valuable, to take on a critical, antiracist stance, individuals must move beyond those experiences to understand the social, cultural, and political forces that have shaped that experience. PSTs in our study mirrored the students in Milner’s (2006) study, who “needed to focus on themselves and their own experiences, life worlds, privileges, struggles, and positions in relation to others” (p. 371) as part of the developmental process of working through their own understanding of racial injustice.

Specifically, to engage in critical racial literacy, individuals need to recognize identities as a structural rather than individual construct (Guinier, 2004; Lewison et al., 2015; Skerrett, 2011). This recognition required the ability to zoom out from the personal to a “proper distance” (Silverstone, 2003) for systemic analysis. Some of our students were not able to fully make that move and, thus, felt safe in their neutral stances (see Falter & Kerkhoff, 2018), while others were able to shift from neutral stances after hearing from students of color, students from other geographic locations, or students with more critical theory knowledge from graduate school.

One related implication for teacher education is that using the personal is only a helpful starting place. We agree with Matias and Grosland (2016) who demonstrated that beginning with one’s own racial identity can help PSTs deconstruct race, and asserted it cannot be an ending place, particularly regarding racial injustice and antiracist teaching. Brandt and Clinton (2002) prompted reflection on “the limits of the local,” as those ideas are partial and often do not recognize the societal and institutional structures of power.

In Sealey-Ruiz’s (2020) racial literacy development framework, after an archaeology of the self has been completed, one must become an “interrupter” in order to claim racial literacy, which even she found difficult to achieve among the college freshman composition students in her course who were examining race and racism all semester (Sealey-Ruiz, 2011, 2013). Given that our students were predominantly White and felt they had limited experiences from which to draw regarding diversity, teacher education courses need to zoom out from the personal to “transcend locality” (Go, 2013) by broadening the perspectives heard within the class. This data showed how some students were able to zoom out and relate the discussions to larger problems in our society – thus, moving from a proximal stance, locating oneself in the conversation context, to a reflexive stance, as students critically examined their positions and theorized about the “difficulties and hope” in communicating with others (Hull & Storniaoulo, 2014, p. 35).

We observed PSTs’ understanding grow as they discussed CPVs across our two universities via Flipgrid. Particularly, we saw how graduate students articulating ideas about difference, racism, and policing helped undergraduates question their own stances and process their reflexivity. In this sense, the students were doing the work of educating each other.

The labor to educate White people about race has been criticized as not the job of Black people. We acknowledge this, and acknowledge that the students who identify as Black did engage in labor to educate their White peers. We also saw White students educating their White peers, and we heard from an undergraduate Black student that she learned from both Black and White graduate students.

We would be remiss not to acknowledge and share gratitude for the labor the Black students undertook (see Norris, 2019 for a philosophical discussion of minimizing epistemic exploitation in academic spaces). Though not perfect, without the digital conversation, this shared dialogue and disruption of the status quo would have been much more challenging.

The instances of peer learning corroborate Adler’s (2011) and Chávez-Reyes’ (2012) findings of the value of discussion with other education students in reconstructing one’s beliefs. By expanding the diversity of opinions in class to those beyond one location, one experience, and one story, students began to consider alternative viewpoints and to reflect on their assumptions. Based on our findings, creating partnerships with classes across program levels, across universities, and across geographic locations was helpful in minimizing “cohort effect” (Ferdig & Roehler, 2003) by furthering students’ abilities to take up critical stances and develop more nuanced racial literacy dispositions due to new and varied perspectives.

The CPV discussions using Flipgrid across universities allowed students to zoom out to consider institutional racism and zoom in on their own personal beliefs. At the same time, Flipgrid as a digital tool mediated geographic distance to bring more voices and, therefore, more diverse perspectives to the classroom. Flipgrid also served to mediate proper distance (Silverstone, 2003) theoretically, as students were able to both hear each other’s voices and see each other’s faces, bringing a humanity to the discussion and making the conversation a place for personal connections. On the other hand, Flipgrid provided emotional distance, because the participants were able to take time to collect their thoughts and word their responses in the best way they knew how.

Our research corroborates Moreillon and Tatarchuk’s (2003) findings that digitally mediated conversations can mediate productive conversations about social issues from diverse perspectives, and contributes to Flipgrid as a tool for conversation on social issues. Future research could examine how to build community across geographic contexts for all participants to feel comfortable sharing their convictions.

Building Solidarity

Our study showed participants building solidarity with their hypothetical, virtual, and face-to-face peers by agreeing with part of their arguments before challenging another part or through building common understandings. Building solidarity happened in a different way because of Flipgrid’s video function. During in-class debriefing about the Flipgrid discussion, Alicia stated that she appreciated the opportunity to converse with another university because she was able to find solidarity with another Black student – something that may not be identifiable in other print-based conversation tools like written discussion board forums. She liked that the discussion was video, because the first thing she did was look for a woman of color to talk to.