In the last decade, the education profession has been met with significant challenges, including increased accountability, decreased state funding in the majority of states (Governing the States and Localities, 2017), stagnant federal funding from 2004 to 2015 (Concordia University, 2016), and a movement toward common academic standards — all of which have translated to shifts in the field. Essentially, school districts and their teachers have been tasked with doing more with less under great pressure, leading to downgrading of the profession and teacher reports of isolation and burnout (Griffith, 2017; Holland, 2017; Pillars, 2014). Many teachers have chosen to leave the profession temporarily or altogether.

With reduced or slowly recovering funding (Governing the States and Localities, 2017), districts have been forced to make difficult choices regarding professional development offerings. As a result of these challenges, teachers who remain in the profession find themselves searching for accessible opportunities for growth, a sense of connection, encouragement, affirmation, and creative outlets related to their work. They sometimes choose informal channels, should formal channels provided by the school district not adequately meet their needs.

Simultaneously, educational research on effective professional development has burgeoned and is available to school leaders and teachers as they seek to understand the best investments of their scarce resources for building capacity and producing positive student outcomes. A need for effective professional development that serves a multitude of purposes and the increased field knowledge of best practices has created a ripe environment for teachers and school leaders to initiate growth opportunities in their schools.

Technological innovations have led to decreased costs as well as the increased access and ownership of personal devices to the point of ubiquity. Innovative, fast-paced development and the saturation of technology in daily lives of students and teachers has led to a familiarity and a comfort level with devices and a minimal learning curve to access new applications.

The proliferation of social media platforms has opened up avenues of communication and sharing that were largely impossible at comparable scale even a few years ago. With virtually no training, consumers can view, share, and create content using media of all kinds — text, images, music, and video — which can be transmitted to countless others with a tap on a handheld screen. Unsurprisingly, this technology shift has impacted the tools, methods, and expectations surrounding schools and the work of teachers.

The intersection of these two forces — shifts in professional development for educators and shifts in technology — has created an opportunity for utilizing unconventional yet increasingly recognized methods of meeting teachers’ needs for professional growth and a sense of connectedness in a cost-effective, technologically enabled way. While there are many manifestations of this phenomenon, one example of this unconventional approach of marrying cost-effective professional development and technological availability is the practice of peer video coaching, a form of instructional coaching with many hallmarks of effective professional development. The purpose of this study is to explore the perceptions of practitioners regarding the value of peer video review as professional development in the graduate school environment and its impact on their instructional practices and sense of professional belonging.

Framework and Literature Review

Literature on professional learning in cultures of continuous improvement frame this study. In particular, the study explores three layers of nested concepts addressing elements of effective professional development, instructional coaching as professional development, and peer instructional coaching through the video share and review process. Desimone and Pak (2017) called for researchers and practitioners to identify “how, when and why coaching models work to create rich classroom experiences” (p. 9). This study explores the experiences of P-12 in-service teachers participating in peer video review while enrolled in a graduate program.

Professional Development

The need for professional development (PD) that leads to genuine teacher learning is clear. To meet academic expectations in schools, teachers must learn and grow in ways that lead to changes in practice and, ultimately, increased student learning. Yet, educators are faced with limited time and myriad PD models and initiatives, making choosing the most effective models a challenge. Learning Forward, the national-level professional learning organization dedicated to “excellent teaching and learning every day” (2015c) recognizes that “professional learning that increases educator effectiveness and results for all students integrates theories, research, and models of human learning to achieve its intended outcomes” (Learning Forward, 2015b, para. 1). For schools, the ultimate intended outcome of PD is increased learning for students and teachers.

Effective PD can be seen as the “linchpin between the present day and new academic goals” in reform (Gulamhussein, 2013, p. 6), and the design of professional learning matters, determining both the quality and effectiveness of the experience (Learning Forward, 2015b). Learning Forward promotes seven standards for professional learning that set the stage to improve teacher effectiveness and capacity and, thus, student academic outcomes (Learning Forward, n.d.). Whether through a formal or informal approach, PD must alter teacher practice to serve the consistent goal of improving learning (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Mizell, 2010). When teachers improve their instructional practices, resulting in increased student learning, PD has been effective (Gulamhussein, 2013; Mizell, 2010). As Mizell stated directly, “When educators learn, students learn more” (p. 19).

Teachers desire professional growth opportunities that involve their voice and choice. Stated differently, teachers desire PD to be done with and for them, not to them; and they know when they have participated in effective PD. Unfortunately, a majority of teachers report that the PD they experience is ineffective (Gulamhussein, 2013). They often do not see a match between their perceived professional needs and the professional development offered to them through formal means (Daniels, Pirayoff, & Bessant, 2013).

As a result, professional development experiences in P-12 education do not connect with teachers’ daily classroom work (Sterrett, Ongaga, & Parker, 2013) or with “what teachers actually want and need in order to authentically improve and/or strengthen their practice” (Daniels et al., 2013, p. 268). In addition to improving instructional practices, participation in effectively designed PD can help build community and collegiality among teachers, resulting in personal growth and renewed enthusiasm for their craft (Nolan & Hoover, 2011).

Extensive research has been devoted to identifying the elements of effective PD and the many forms it can take. After a thorough review of three decades’ worth of professional development literature, Darling-Hammond et al., (2017) identified seven common components of effective professional development. They determined that effective PD is content focused, incorporates active learning, supports collaboration, uses models of effective practice, provides coaching and expert support, offers feedback and reflection, and is of sustained duration.

Wilson and Berne (1999) took a broader view and identified three elements of effective PD programs: community learning that addresses teacher practice, an activation of learning and inquiry toward teaching, and an atmosphere of trust and professionally critical discussion.

Instructional Coaching as PD

PD can appear in many forms, including the commonly named but increasingly diverse practice of coaching. Recent practice sees instructional coaches assigned to their roles based on an increasing variety of identified instructional needs, including subject-matter expertise in literacy, mathematics, data, and technology (Tschannen-Moran & Tschannen-Moran, 2011). The traditional role of expert teachers as coaches is expanding. Principals and district instructional leaders are serving as coaches for teachers, as are school-based expert teachers and teaching peers. “Embraced by administrators and teachers alike, coaching has become a vital tool of professionalism” (para. 13).

Successful schools create “learning communities that are committed to continuous improvement, collective responsibility, and goal alignment” (Learning Forward, 2015a, para. 1), and instructional coaching offers one model of professional development that is focused on improvement through learning communities. Through the identification of expert teachers who can serve as coaches and mentors for their peers, schools can create learning communities that produce the desired collective responsibility and goal alignment that bring improvements in student learning (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). Expert teachers can support improvement efforts as valuable resources in leading school change (Wolpert-Gawron, 2016).

In a meta-analysis of the most effective elements of instructional coaching, Desimone and Pak (2017) noted that instructional coaching is increasingly popular, but little empirical evidence exists to support its value and impact on teaching practices. After a deep study of instructional coaching literature and practices, the authors identified a framework for high quality instructional coaching built upon five key features: content focus, active learning, sustained duration, coherence, and collective participation.

Instructional coaching is, by nature, active learning that can take many forms. Instructional coaching, observing a lesson and debriefing it afterward with the purpose of analysis and discussion, can occur in person or through sharing a video recorded lesson (Desimone & Pak, 2017). Coaching can involve teachers from a range of experience levels, focus on any content area, and support ongoing professional relationships. This form of active learning does not need to involve only one one teacher and one coach; it can include elements of group or team coaching.

Effective coaching facilitates engagement through observation and feedback, empowering teachers. It promotes coherence, connecting learning to teachers’ daily work and the improvements they wish to implement. According to Connor (2017), “Dialogue between coaches and teachers, for some models, among teachers as fellow professionals, is more likely to make sustained changes in practice than more traditional workshop and lecture” (p. 87).

Desimone and Pak’s (2017) collective participation construct involves a social environment of discussion to address a variety of relevant issues such as instructional practices. Effective instructional coaching makes teachers feel empowered to try new practices and helps teachers be more attentive to basing instruction on student needs (Vanderburg & Stevens, 2010). Such instructional sharing and discussion may take on the form of Desimone and Pak’s collective participation, involving team coaching to provide immediate, real-time feedback for teachers exploring new practices (Blakely, 2001).

Teachers involved in coaching can benefit from collaboration beyond their grade levels and content areas. Vanderburg and Stevens (2010) cited the value of discussion and coaching that helps teachers learn about and better understand other classrooms on their grade level and across the entire school, creating a vertical understanding of content taught.

Borko, Jacobs, Eiteljorg, and Pittman (2008) recognized team coaching as a means of reducing isolation, as teachers see other’s situations and similar problems. Regardless of the form of instructional sharing, it is imperative that districts provide opportunities for coaching and collaboration, or teachers, with their extensive load of responsibilities, simply will have limited access to the experience and likely will not find time to make coaching happen (White, Howell Smith, Kunz, & Nugent, 2015).

As a subset of instructional coaching, peer coaching shares numerous characteristics of more formal models of coaching with one notable difference: the removal of hierarchy between coach and coachee. Peer coaching may include coaching delivered by expert teachers, peer study groups with communal areas of focus, and peer observations (Mizell, 2010). In peer coaching, all parties seek out skilled colleagues and have something to give and receive. Peer coaching participants enter into a learning community as equals, focusing on the common goal of elevating each other’s practice. In theory, all instructional coaching creates a communal study of teacher practice, but some coaching relationships can potentially set up an imbalance of power between coach and coachee (Welman & Bachkirova, 2010).

Peer coaching, as effective PD, promotes teachers learning from each other (Sterrett et al., 2013). This practice must begin with a thoughtful structure, what Learning Forward (2015b) labeled as a “learning design,” and can involve one or any combination of numerous forms including, but not limited to, peer observation, peer classroom visits, peer and expert coaching, teacher discussion groups, analysis of instructional practice, and video clubs (see also Mizell, 2010).

In creating a collaborative environment that pairs peer observations and peer coaching with supportive, reflective discussion regarding practice can enhance communication and professionalism and support teacher improvement (Learning Forward, 2015b; Daniels et al., 2013). Implemented correctly, effective learning communities, such as those found in successful peer coaching, can lead to “widespread improvement within and beyond the school level” (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017, para. 12).

Charlotte Danielson (2007), internationally known for her work with teacher effectiveness and teacher professional learning, identifies self-assessment and peer discussion as time well spent for teachers. In practice, peer coaching design may be formal or informal, but the critical component is the peer, and the key element involves engagement through teacher commitment to continual learning and improvement. The communal aspect of peer coaching is a critical component as the learning community experience fosters teacher efficacy and confidence (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

Successful learning communities allow participants to focus on areas of growth and common goals. Peer observation centered on a central question and discussed in a non-evaluative context “positively influences teacher attitude and practice” (Daniels et al., 2013, p. 274). In addition to a clear focus on a shared problem of practice, active inquiry and engagement among participating teachers contribute to the success of learning communities and the teachers who participate in them (King, 2016). Inquiry and active engagement, with peers and with the content, help teachers establish commitment to and deep understanding of their new learning, supporting implementation and improved practice (Learning Forward, 2015b).

Peer Video Review with Colleagues as Coaches

The use of digital technology for recording and sharing instruction through coaching and peer video share is gaining prominence (Beisiegel, Mitchell, & Hill, 2018; Forsythe & Johnson, 2017; van Es, Tunney, Goldsmith, & Seago, 2014). Such technology is increasingly enhancing opportunities for teachers to participate in personalized learning through a communal practice of analyzing and constructing knowledge around their own teaching (Learning Forward, 2015a, 2015b).

Implemented correctly, video review can help teachers build new knowledge and skills and, like other coaching, can be facilitated by peers, experienced peers, principals and other school district leaders, university faculty, or researchers. A critical distinction, however, must be made between formal PD with video sharing that involves a trained, nonpeer, facilitator/coach and video sharing among colleagues of equal stature in a nonevaluative, growth-minded manner. Such sharing is emerging in practice and literature as peer video clubs.

In peer video clubs, rather than simply discussing instruction in isolation or visiting peer classrooms followed by discussion, teachers gather in small groups to simultaneously watch and discuss recordings of their own and each other’s instruction. Video clubs are not designed for peer evaluation. Instead, the intended goal is for teachers to better understand their own and other’s teaching and learning (Sherin & Han, 2004), fostering an environment of learning, communication, reflection, and collaboration among teachers (Sterrett, Dikkers, & Parker, 2014).

A practical component of the use of video to study teaching is the ability of teachers to pause, replay, and revisit their instruction. Video allows teachers to take time to more deeply study and analyze an instructional moment (Rosaen, Lundeberg, Cooper, Fritzen, & Terpstra, 2008). The structure of video clubs, where multiple participants with multiple viewpoints can rewatch key classroom moments, supports teachers in seeing both students and subject matter from new perspectives (Knight et al., 2012).

Participation in peer coaching, through sharing and discussing instruction videos, can help teachers learn to interpret their practice more deeply than in an initial surface level view. Peer video review can play an important, positive role in establishing and growing what Sherin and van Es (2009) termed “professional vision” and “noticing.”

According to Sherin and van Es (2009), professional vision involves teachers’ ability to more deeply pay attention to and interpret what is happening in their classrooms. The researchers defined noticing, a component of professional vision, as three skills: being able to identify “what is important in a teaching situation; using what one knows about the context to reason about a situation; and making connections between specific events and broader principles of teaching and learning” (van Es & Sherin, 2008, p. 245).

In studying the impact of video club participation on the development of teachers’ professional vision, Sherin and van Es (2009) argued that all teachers, even experienced teachers who know how to analyze what is happening in a classroom, can use video review to focus on student thinking and learning, rather than teacher actions, thus improving their professional vision and noticing skills. When properly facilitated, “video viewing is a unique and potentially powerful tool” that can help teachers improve instruction and “modernize education” (Gaudin & Chaliès, 2015, p. 59).

Peer video sharing does not come without complications. Teachers may feel uncomfortable, at least at first, seeing themselves on video and in action. This is still a rare practice for most teachers. Watching themselves on video can be distracting and cause teachers to be preoccupied with their appearance rather than their teaching and student learning (Nolan & Hoover, 2011). Additionally, classroom interactions can be too complex to catch everything that is happening.

To make an instructional video most valuable, teachers must carefully identify the specific goal of their recorded instruction (Nolan & Hoover, 2011), which naturally will lead to the exclusion of other classroom events (Miller & Zhou, 2007). This approach will narrow the view of the classroom for those watching the video, which can be negative or positive, as a narrow video focus can make a viewer miss relevant classroom activity or can help focus peer group discussion (Forsythe & Johnson, 2017).

The use of technology in coaching has the potential to offer practical benefits, allowing for real time, immediate viewing, and discussion, as well as access to peers and coaches across distances. Additionally, the appropriate use of technology in any form of coaching can allow for increased efficiency, resulting in financial benefits through cost reduction and increased potential for scalability (Connor, 2017).

At the most practical level, teachers can participate in video review and self-reflection on their own, but the value of collaboration through peer discussion and feedback is strong (Borko et al., 2008; Daniels et al., 2013; Vanderburg & Stevens, 2010). Such collaborative work can be formal or informal, initiated by school leadership, a graduate school program, or in a grassroots format by a group of enthusiastic teachers.

In a professional article from 2012, Jean Clark discussed the application of video study groups among teaching practitioners. Clark reported the following four benefits of video study groups as learning teams (Knight et al., 2012):

- Teachers learn a great deal by watching themselves teach, especially after they have watched themselves several times.

- Video study groups are good follow-up to professional learning by increasing the likelihood and quality of implementation after training.

- The dialogue that occurs during video study groups deepens group members’ understanding of how to teach the targeted practice and often introduces them to other teaching practices while watching others teach and listening to team members’ comments.

- When teachers come together for such conversation, they often form a meaningful bond because the structure of a video study group compels everyone to stand vulnerably in front of their peers and engage in constructive, supportive, and appreciative conversations with colleagues. Those bonds may ultimately be more important than all of the other learning that occurs since they create supportive, positive relationships among peers. (p. 21)

Effective PD can take on a variety of forms, including “enrollment in graduate courses…peer coaching, action research and collegial development groups,” among others (Nolan & Hoover, 2011, p. 74). The combination of these practices, with the addition of video recorded instruction, sets a stage for Mizell’s (2010) desired teacher learning that can influence student learning. This study utilized the interplay of collaboration, coaching and expert support, feedback and reflection (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017), with community learning in a graduate school setting that addressed inquiry regarding teacher practice and an atmosphere of trust and professionally critical discussion (Wilson & Berne, 1999).

Using Backchannels in Peer Video Reviews

In recent investigations, we conducted cycles of peer video review with in-service teachers enrolled in a graduate course aimed at developing reflective practice skills. Course requirements involved study and discussion of the participants’ practices as teachers. Participants identified an area of instructional focus, consulted the related literature, created a brief rubric targeting the area of focus, piloted the rubric by observing peers in their own schools, and then then asked classmates to use the rubric as a frame for examining their recorded instruction.

Teachers video-recorded their classroom instruction and shared in small peer groups, providing each other with feedback, both orally and through a shared digital space. We implemented backchannels, or digital chat rooms, to allow for real-time conversation while the video was being viewed, and subsequently, we sought to examine the nature and quality of peer feedback exchanged in the collaborative space.

Additionally, we surveyed participants about the nature and quality of peer feedback exchanged through backchannel during the video share, their perceptions of the backchannel tool for a wide range of educational applications, and their perceptions of the sharing experience. Data collection took place with multiple cohorts over a 5-year period.

Through the backchannel, participants made observations, gave compliments, and offered helpful coaching prompts to one another, all mostly positive or neutral in tone. The content of the conversations focused heavily on instructional strategies, teacher behavior, and aspects of the learning environment evident in the video footage. Survey results indicated a general sense of trust among group members and an acknowledgement that group members provided feedback for the purpose of promoting growth. Additionally, the structure of the peer video review session paired with a backchannel was perceived as valuable, easy-to-use, engaging, and collaborative and as a mechanism for giving and receiving high-quality feedback (Kassner & Cassada, 2017).

The 2017 article focused specifically on integrating the backchannel in the peer sharing experience. After reading Knight et al.’s (2012) practitioner-focused piece on peer video sharing groups, we reflected on our experiences and data sets with new lenses. Additional unpublished findings from our 2013-2017 study include participant perspectives on the peer video share experience, which was less of the focus of our inquiry at the time. In surveys, participants generally acknowledged feeling hesitation and anxiety prior to their video sharing moment with peers, but expressed, after the peer group session, that they had found comfort sharing videotaped instruction in their small groups and an acknowledgement that small group partners provided feedback for the purpose of growth.

Knight et al.’s work (2012) resonated strongly with our findings, both published and unpublished, and the four benefits outlined in the article by Knight and his colleagues mirrored the themes discussed informally and consistently by our student participants at the summation of the peer video review exercise in class. As a result, we wished to dig deeper, formalize the participant feedback, and analyze and share their feedback. Clark’s themes (Knight et al., 2012) prompted us to inquire further, in open-ended qualitative ways, with our peer video review participants about the value of video review as a form of effective peer coaching. Thus, we utilized Knight et al.’s article as a lens for further inquiry in this study.

Methodology

The purpose of this study was to assess the perception of in-service teachers related to their peer video review experiences in a graduate teacher-education course, utilizing Clark’s (as cited in Knight et al., 2012) four identified benefits to peer video coaching as a lens for study.

Participants

This study utilized previous study participants from our reflective peer video review work in 2013, 2014, and 2015, as well as students from the spring 2017 course, all of whom had the shared experience of peer video review and feedback in their graduate education classes. Since 2013, a total of 38 students participated in two cycles of video review each, for a total of 76 collaborative peer coaching video experiences.

All 38 past students were contacted via email with links to an online survey, focusing on the peer video review experience, perceptions of the value of the peer video review practice, and its impact on their instructional practices. University email addresses were used for all students, approximately 80% of whom had graduated from the program. When known, work email addresses were also employed as a means of contacting participants.

The University’s Institutional Review Board approved and supervised the study. Participation was voluntary, anonymity was ensured, and consent was obtained at the beginning of the survey.

Data Gathering and Protocol

Emails to past students included a link to an online survey that asked them to share their graduate class experiences with peer video review in light of the four benefits of peer video review identified by Clark (as cited in Knight et al., 2012). The protocol (see appendix) included prompting questions to assess participant agreement or disagreement and to stimulate significant qualitative responses.

Data Analysis

In response to the survey request and protocol, the 10 teachers who participated in the survey submitted narrative responses of varying length and depth, totalling over 3,100 words of commentary. The participant responses were analyzed qualitatively for thematic patterns using a grounded theory approach with open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 2010).

We coded together, discussing schema and thematic findings to ensure consistency. Responses generated by the survey involved many interrelated concepts and tended to overlap multiple topics. As a result, the decision was made to report findings thematically across the survey questions that were based on Clark’s identified benefits to peer video coaching (Knight et al., 2012).

Findings

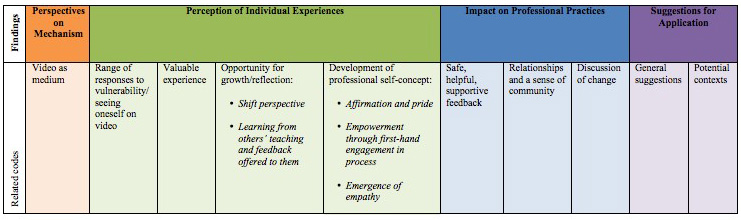

The purpose of this study was to assess the perceptions of in-service teachers related to their peer video review experiences in a graduate teacher-education course, utilizing Clark’s four identified benefits to peer video coaching as a lens (Knight et al., 2012). Qualitative analysis of participant responses yielded four categories of findings: (a) perspectives on mechanism of peer video review, (b) perception of individual experiences, (c) impact on professional practices, and (d) suggestions for application. Figure 1 illustrates the four findings and their related codes.

Perspectives on Mechanism of Peer Video Review

Participants acknowledged positive aspects to utilizing prerecorded video of instruction for peer coaching sessions, including ease of use. They noted the ability to freeze time, replay, rewind and rewatch the recording. One noted, “It is a different experience to see yourself do something and have feedback versus not having the video and only a written critique.” Participants expressed an appreciation for seeing practice in action, noting, “Seeing/hearing how others teach is much more beneficial than talking about what other teachers do or reading about what they do. We rarely have opportunities to do peer observations so the videos help to spotlight best practices.”

While video offers participants the ability to relive and study the recording an endless number of times, two students did not watch their recordings at all prior to the group share, and three watched once; other students reported watching their videos between two and five times. None reported watching the video footage after the shared peer coaching session in class.

Perception of Individual Experiences

Range of Responses to Vulnerability/Seeing Oneself on Video. While a few respondents were comfortable with viewing themselves teaching (having had past experience seeing themselves professionally on camera), most respondents expressed a sense of anxiety and nervousness related to such vulnerability. Most participants who conveyed nervousness referenced their professional practices, as evidenced by these statements:

- “I did not like watching myself…but I actually took the time instead to watch what my students were doing.”

- “I was most fearful sharing it with others because of a perceived embarrassment over my teaching methods.”

- “I was nervous about my video because I never watched myself teach.”

One respondent indicated her fear was more about self-consciousness related to appearance: “When I first thought of recording myself, I didn’t like the idea of seeing myself on video. But then when I watched it with my peers, it wasn’t that bad.”

Valuable Experience. While initial anxiety was broadly expressed surrounding watching oneself on video, overwhelmingly the experience was viewed after the fact as beneficial and helpful to participants in ways that will be explored in subsequent findings. One respondent summarized this tension between the challenge and the value by stating, “As hard as it is to watch myself, I do think it helped me grow in my practice.” Echoing the impact of the practice, another respondent stated, “It was an extremely powerful tool that impacted my teaching considerably; it’s also extremely simple and it is surprising that it doesn’t occur more often with teachers.”

Opportunity for Growth and Reflection.

Shift perspective. One way in which participants described the peer video review experience as helpful was the ability to shift perspective and view classroom happenings as an outsider. One used the phrase “outside looking in,” describing the feeling of being an observer to the scene. Numerous respondents noted their interest in focusing on their students, saying, “I can more easily see how my students respond to me as I teach,” and “I didn’t realize the kids I was losing, as far as attention was concerned.” Allowing teachers to relive a scene in their daily professional life also led to the ability to notice new elements of classroom happenings in more depth, as two respondents noted.

Learning from others’ teaching and feedback offered to them. A few respondents mentioned the benefit of being able to see other professionals’ classrooms in action, and they underscored the added benefit of listening in on the feedback given to others in these peer video review configurations. One stated, “I learned from when I received feedback from my peers, but I also learned by watching my peers and hearing the feedback shared for them as well.”

Development of Professional Self-Concept. Participants indicated changes in their feelings related to their professional identity, including a sense of affirmation and pride, a sense of empowerment, and the emergency of empathy.

Affirmation and pride. A number of respondents noted how the peer video review experience provided them with a sense of affirmation of their practices. One stated, “I found it affirming, as I am a veteran teacher…. Often I have felt good about my delivery and my acquired skills, and this helped to confirm my choice of profession.” Another stated, “It was awesome to have people to uplift me and point out my positive points.”

Viewing recorded instruction also inspired a sense of pride, with respondents commenting, “I was proud to witness the progression that I saw when teaching concerning my students,” and “I saw the connection I had with my students.”

Empowerment through firsthand engagement in process. In contrast to typical observations conducted by administrators for the purpose of evaluation, the peer review was collaborative, participatory, and engaging. One respondent stated, “Just having the time to reflect on our teaching by seeing for ourselves (not through someone else’s interpretation) is so valuable and is something we don’t get to do enough!” Unlike evaluation done to teachers, peer review gave them a structure for reflection done with and for them.

Emergence of empathy. Participants spanned the P-12 spectrum, teaching in both regular education and special education environments. Evidence of empathy and respect for each other, given the varieties in teaching assignments, emerged. One stated, “In my opinion, middle and high school teachers have it much harder than elementary [teachers].” Another respondent noted, “For me, I was introduced to the elementary world of 2017, and I really do appreciate the challenges my colleagues face at this level.”

Impact on Professional Practices

Safe, Helpful, Supportive Feedback. Some participants highlighted the safety they felt in the peer video review context, because the experience occurred in a learning community. It was done with and for them, unlike evaluation which can feel like it is done to a teacher.

- “Peers critiquing me were nonthreatening, since I knew them and we were all in it together.”

- “As it turns out it was very helpful to have feedback, and they were supportive instead of critical.”

- “They gave me tips and helpful remarks and in a judgement free zone.”

One warned of the danger of sacrificing depth for kindness, noting, “Teachers were kind to others, so ‘real’ feedback was limited.”

Relationships and a Sense of Community. Several participants addressed the topic of relationships and bonds in the classroom community, with varying intensity. On the positive end, one credited the peer video review as a catalyst for bonding, saying,

I did not feel as connected to my classmates until we had that experience as a group. Now I miss them and wish I will have more classes with them. The experience really helped to facilitate our work with each other and to help each other to reflect, especially when we could see what others necessarily could not because they may have been overly critical of themselves.

One participant spoke of the ongoing collaborative nature of sharing and supporting each other, characteristic of a group with a high sense of community: “You worked with your peers sharing insights and support to continue helping each other grow.” Another student spoke of a permanent sense of community that would carry on beyond the semester:

I will not forget the people who were in this class. I loved hearing about their experiences, and they really encouraged me during a very difficult transition in my career. I was excited to see my peers teach and see how they handled different situations. It was awesome to have people to uplift me and point out my positive points.

Not all commented on a positive sense of community. One participant explicitly stated that peer video review did not provide a bonding experience, and another highlighted the risks of such intimate vulnerability beyond comfort levels, by saying, “Teachers are very critical with themselves and can shut down instead of allowing this vulnerability.”

Discussion of change. Numerous respondents talked about the impact of peer review on their practice, discussing the concept of change. One indicated no change, but said the video review affirmed their thoughts on good practice. Another hinted at a willingness to change, but overall satisfaction with their practice:

I do not feel I have changed too much based on the videos and conversations I presented but would be interested in doing something like this again to continue to look at my instruction and see where change is needed.

Four others provided examples of ways that they had changed since the peer video review:

- “I believe I changed my ratio of direct instruction to small group work.”

- “I was able to see what level of questioning I used and adjust to go higher to make my students grow.”

- “I am not favoring one part of the room over another any longer.”

- “I do believe that I have differentiated instruction more.”

Suggestions for Application

General Suggestions. When participants were asked if there was anything else they wished to share about the peer video review experience, a number of practical suggestions emerged. One suggested that group members watch the videos ahead of time, write down thoughts, then watch collectively and share their thoughts. Another suggested grouping teachers more closely by the age range of children they serve, so the conversations and practices are more relatable to all in the group.

One suggested peer video review occur more frequently, stating, “Just having the time to reflect on our teaching … is something we don’t get to do enough.” Another respondent noted peer video review would be effective in helping teachers identify and target specific classroom practices for study, citing “wait time, creating a welcoming environment, and levels of questioning” as examples. Completing multiple rounds of peer video review, shifting the instructional focus each time, was another suggested application.

Potential Contexts. Participants suggested ways to carry the benefits of peer video review from the graduate school environment to other contexts of teachers’ professional lives. One survey respondent made the suggestion of integrating peer video review into the teacher evaluation process: “I wish that instead of several observations by administration we could replace one or two of those with peer video reviews or even just a self-evaluation of our own videos that we then submit to the administration.”

Several respondents highlighted the potential to use peer video review structures for mentor and teacher leadership, particularly with novice teachers in the induction and mentoring processes. One more-experienced teacher noted, “As a veteran, I was able to really provide thoughtful suggestions to other less experienced teachers,” while a novice teacher noted, “I was able to ask them to look for or trouble shoot certain things, and it was really helpful to have extra sets of eyes with years of experience to help me brainstorm solutions.” A third participant stated, “I can truly see this as invaluable for teachers who have not had countless observations and who are in the first five years of their career.”

Limitations

The survey was distributed to all original participants of the peer video review experience (four groups between 2013 and 2017). Out of 38 total participants we attempted to contact, 10 responded, yielding a 26% response rate. We anticipated low response rates based on the knowledge that more than 80% of participants we attempted to reach were students who had already graduated from the program. We used university email addresses unless other contact information had been shared by students; we did not know how many participants retained or used their university email addresses after graduation. In addition, participants have been removed from the experience for a range of a few months to 4 years. Most, if not all, participants are full-time educators with significant time commitments that might have precluded participation. That said, the 10 who responded provided rich feedback with a variety of opinions, which gave balance to the discussion.

Discussion

Peer video review offers promising outcomes as a mechanism for professional development that involves teachers meaningfully in their own growth. To more deeply understand the benefits, challenges, and potential applications of peer video review, this study sought peer video review participants’ feedback on the process, as experienced in a graduate school reflective teaching course. The questions posed to participants were framed around Clark’s four identified benefits of peer video review (Knight et al., 2012).

Connecting to Clark’s Four Stated Benefits of Peer Video Review

While the responses to the protocol involved many interrelated concepts that were analyzed holistically, for framing purposes of this study’s findings the responses were reconnected to Clark’s four stated benefits of peer video review (Knight et al., 2012).

Benefit 1. Participants indicated significant learning — about their practices, their students, their professional identities, and their peers — through peer video review. While some respondents indicated they previewed the video (six respondents stated they viewed it between one and five times) before bringing it to their classmates for the sharing session, some (two respondents out of 10) did not preview it, and none responded that they viewed the recording postsharing session. Thus, the component of watching several times was weak, as teachers watched between one and six times throughout the entire process (including group viewing). Yet, overall, watching themselves teach in a collaborative setting with feedback from peers was cited as highly valuable and meaningful.

Benefit 2. No specific common instructional strategy-focused PD preceded the peer video review (as found in Clark’s work), given that the participants had unique teaching assignments in diverse classrooms, schools, and school systems. Yet, all participated in a similar process of researching an instructional area of focus and creating a differentiated peer observation rubric through a common graduate level class. Some respondents reported changed practice as a result of the peer video review experience.

Benefit 3. Participants spoke of the benefit of seeing instructional strategies in practice in real classrooms, referencing the benefit of learning new strategies and ideas, as well as listening to the feedback provided to them and to their peers. A veteran teacher carried this sentiment further by noting the ability to offer suggestions and experienced insight to younger teachers.

Benefit 4. Several participants noted the helpfulness of supportive colleagues, the vulnerability required for such an exercise, the safe space created by like-minded peers, and the strength of relationships formed through the experience. The majority of comments expressed sentiment strongly agreeing with Benefit 4, noting that trust was strengthened and stating, “This is absolutely true…. Now I miss them and wish I had more classes with them,” and “I will not forget the people in this class.” One participant disagreed with the Benefit 4, stating rather, “I don’t think it changed at all…. I didn’t build better relationships due to the video.” However, even this individual commented on the positive value of the peer video share practice.

Additional Findings

In reflecting on participants’ survey responses and existing literature regarding peer video review as effective PD, important implications arose beyond the connections to Clarks’ four benefits of peer video review for the broader context of teacher professional learning and growth. Participant responses, paired with literature in the field, affirmed that the practice of teachers recording their instruction and sharing it with peers is initially intimidating, but ultimately worthwhile. The strategy had an impact on participants’ personal and professional views of their practice as teachers.

Participants reported advantages of the practice as PD, including access to the process and ease of use, influences on reflection and self-concept, creating the culture of a learning community, and a focus on continuous improvement. Respondents also provided insights into possible applications for practices across contexts, including teacher preparation, teacher mentoring and induction, observation and evaluation procedures, continuing education for in-service teachers, and higher education.

High Quality PD. Peer video review exemplifies many hallmarks of high quality PD, specifically the aspects of job-embeddedness, relevance and authenticity, personalization, and active engagement. In a meta-analysis of the most effective elements of instructional coaching as high quality professional development, Desimone and Pak (2017) identified a coaching framework that includes features related to active learning, coherence (learning opportunities that are connected and relevant to the work), and collective participation, all of which are supported by the peer video review approach.

While shortcomings of traditional PD formats often are reported as feeling disconnected and unrelated to real challenges in the classroom, focusing on the improvement of teaching and learning through the study of teachers’ actual instructional practices using peer video review is by definition job-embedded, relevant, and authentic. It personalizes the learning for teachers by honing in on their own weaknesses and strengths, and feedback can be elicited specific to their needs, making the learning experience deeply meaningful.

When implemented in a group of peers in parallel position (no hierarchy or leadership roles), peer video reviews have the opportunity to take on the characteristics of grassroots PD, teacher led and directed (Gaudin & Chaliès, 2015; Moore, 2008). In group configurations, everyone has something to notice, to share, and to offer, promoting active engagement of all participants in the PD process. It is the opposite of the many eye-roll inducing traditional PD sessions done to teachers without their voice and choice; instead it is PD done with and for the teachers in a deeply personal, meaningful, and relevant way.

Advantages of Peer Video Review Format. Participants found the sharing of digital video fairly easy to accomplish, presumably because of the ubiquity of personal digital devices and the common practice of sharing videos via social media. Connor (2017) also discussed the efficiencies actualized in this format through reduced costs and potential for scalability. Traditional forms of PD, such as graduate courses and professional conferences, are highly expensive. In contrast, peer video review is practically free, costing only time. Personal digital devices, internet connectivity, and social media accounts are ubiquitous, making the process low-cost, efficient, and easy to learn and replicate.

In addition to the simplicity, savings, and scalability of recording and sharing, the ability to record and replay instructional videos at a different time and location helps overcome challenges inherent in traditional in-person peer observations. Video can be watched as often as desired, in advance of the sharing experience or at a later date and time, following the group share (Beisiegel et al., 2018; Gaudin & Chaliès, 2015; Rosaen et al., 2008).

Often teachers on the same grade level teams have common planning time, which is excellent for collaboration but challenging when trying to view each other teaching live. This technology and structure can solve the problem of access. Furthermore, educator are not restricted to being observed by colleagues in close proximity, as they can seek out respected peers across wide geographic expanses. This strategy may be particularly helpful for teachers working in school cultures that are not yet defined by collaboration and vulnerability, as they can seek out peers anywhere.

Reflection, Metacognition, and Professional Self-Concept. Another unique aspect of video review, as opposed to traditional in-person, third-party observations, is the ability to shift perspective and see oneself in action (Knight et al., 2012; Sherin & van Es, 2009) and even move beyond the experience from the teacher’s perspective, shifting instead to the experiences of students in the classroom (Vanderburg & Stevens, 2010). Rosaen et al. (2008) described the “slowing down” effect of video, allowing the viewers to transcend the normal boundaries of time, to hit pause, think, rewind, and rewatch.

Teachers can improve their professional vision and noticing skills through video club participation (Sherin & Han, 2004). Video reviews can have great value, even apart from the peer feedback component, as professionals can reflect and see themselves in new ways, perhaps confronting their long-held beliefs about their own practice. Relatedly, coming face to face with one’s self through video review is connected to the development — or even evolution — of self-concept and professional efficacy (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

Culture of Sharing, Sense of Community. Most participants in our study spoke of initial fear and apprehension about sharing their videos with peers, citing discomfort with that level of vulnerability with colleagues, but most participants also cited the value of the experience in affirming their practices, providing them new ideas, exposing them to new perspectives, and building a bond with their classmates. These findings affirm the benefits outlined by Knight et al. (2012) once the barrier of fear is broken and speak to the valuable and transformative experience peer video reviews provide when experienced in a collaborative context with supportive colleagues.

Additionally, participants spoke of empathy and respect for their colleagues working with different populations and age levels of students. Benefits of peer coaching acknowledged in the literature include exposure to and learning about teaching in other classrooms and grades (Vanderburg & Stevens, 2010) as well as an appreciation of and empathy for colleagues (Sterrett et al., 2013). Participants also spoke of seeing others’ situations and challenges, reducing their own sense of isolation (as in Borko et al., 2008).

Making the time to connect meaningfully with colleagues regarding their practice emerges in professional literature as a real need among teachers. From the perspective of a practitioner, Tonishia Short, a recognized and skilled educator who took a year off from teaching, lamented her professional frustration in a Center for Teacher Quality blog: “Do we allow [teachers] to learn from their peers? If a teacher is struggling with classroom transitions do we allow her to consult with a master teacher in the building to help her learn a few tips and strategies? We have ‘sleeping giants’ in our schools” (Holland, 2017, para. 15).

A culture of sharing and learning is what should characterize the education profession, as the chief job of leaders of learning is to learn continuously, ourselves. By modeling transparency, embracing a reflective posture, and harnessing the collective brain trust, educators not only get better in practice, but better at getting better. The side effects of building such a collaborative and supportive learning culture include strong camaraderie, meaningful bonds, and a powerful sense of connection to each other and to the profession.

Practice-Focused Continuous Improvement at the Classroom Level. Video clubs have the potential to support educational reform efforts (Sherin & Han, 2004). By using the format of peer video review across departments, schools, and systems, examination of instructional practices and strategies for improvement becomes the focus of school improvement at the classroom level — in every classroom — bringing about more coordinated, comprehensive, cohesive change. This change can empower teachers to believe they are part of the solution and critical actors for change, boosting their efficacy related to changing outcomes for students.

When implemented within a broader culture of continuous improvement, peer video review helps elevate the craft of teaching through collective and reflective examination and the affirmation of what good instruction looks, sounds, and feels like. Peer video review is intended to support teachers’ better understanding of teaching and learning in a nonevaluative context (Sherin & Han, 2004). As our participants suggested, peer video review has promise in working with new teachers and in mentoring relationships.

The format may also be integrated into preexisting structures of professional learning communities (DuFour & Eaker, 1998). Many parallels exist between peer video review and the video reflection components of the National Board Certification process (National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, 2017a), which is one effective, nontraditional PD experience (Cohen & Rice, 2005; Jones, 2015;) and recognized as a quality indicator in some empirical studies (National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, 2017b).

Closing

Traditional professional development and feedback mechanisms for teachers are often prescriptive, one-size-fits-all, and unidirectional, from expert or evaluator to teacher. Figure 2 summarizes common PD formats, moving to progressively complex, differentiated, and teacher-centered learning opportunities, culminating in peer video reviews. While collaborative learning through traditional PD has merit, and video review and self-reflection can take place in isolation, engaging in peer video review combines the strengths of collaboration with self-reflection on the primary source of the video footage — and the strength of this format lives at this intersection (Borko et al., 2008; Daniels et al., 2013; Vanderburg & Stevens, 2010).

Figure 3 illustrates the interactions surrounding this intersection. The opportunities for connection, collaboration, perspective-shifting, and idea-sharing are a great strength of peer video reviews, and the value of these interpersonal exchanges is not replicated at the same level in the other formats.

Charlotte Danielson (2007) said, “Time is well spent when peers conduct self-assessments and then discuss areas of perceived weakness and strength with each other” (p. 176). When so much competes for the time of educators, ensuring time is well spent should be the commitment and gold standard of PD leadership efforts. Nationally recognized educator, Renee Moore (2016), in a recent Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development blog addressing how teachers learn, recommended,

Whenever possible, districts should opt for teacher-led PD, giving participants ample time to collaborate with each other, practice new ideas or techniques, and get ongoing support for their implementation. We also encourage local PD planners to … provide ample opportunities for teachers to model, practice, question, and evaluate classroom practices … [and] make use of available technology, including social media, that could enhance collaboration among teachers across levels, subject areas, or buildings. (para. 7)

While peer video reviews do not have the corner of the market on effective PD characteristics to answer this call, they can be utilized as a part of a “balanced professional learning diet” (Swanson, 2014, p. 40) along with other active, job-embedded learning designs that focus on the “transfer of learning to practice” and facilitate “construct[ion] of personal meaning… deep understanding of new learning and increase [the] motivation to implement it” (Learning Forward, 2015b, para. 8).

Implications

The findings of this study have implications for teachers, educational leaders, and faculty of teacher preparation and graduate education programs.

For Teachers. Based on the feedback from participants, the peer video review process can help teachers overcome fears of vulnerability and embrace the benefits of a professional community. Teachers are not alone in this challenging profession. Peer video review can be tried in the absence of or as a supplement to formal PD structures in a school district. Teachers can seek out like-minded colleagues who are willing to grow and connect with others they respect. They can learn and pay it forward by encouraging others, newcomers and veterans alike. Technology can be harnessed to remove barriers related to connection and collaboration over distances. No one is confined to the four walls of a school. P-12 students can also be engaged in peer video review experiences in the classroom to help them build reflective skills and a sense of classroom community.

For Educational Leaders. While vibrant, trusting, professional communities are not built overnight, educational leaders can take steps to build a culture of sharing and providing feedback in their spheres of influence. Given the low cost and minimal barriers to implementation, this accessible form of PD can be tried with staff, empowering them through participation. Leaders should create and protect time for them to collaborate, share, and reflect with each other. Principals and other school leaders are encouraged to foster, facilitate, and equip teachers to engage in peer observation with video, with a goal of improving practice, communication, collaboration, and awareness of peer instruction and content around school.

Peer video review is a mechanism to personalize PD, pursuing growth with and for teachers, as opposed to sitting back from a distance and subjecting them to traditional PD done to them. To build buy-in and comfort levels, leaders can leverage video libraries of recorded instruction to build capacity for giving good feedback without the anxiety and vulnerability of personal recordings. Peer facilitators may need help to gain training and skill. Leaders should read, study, share, and explore professional literature on high quality feedback. Once trust and comfort levels have been established, peer video review experiences can be used to work through implementation dips in acquiring new skillsets in large-scale initiatives, where everyone is focused on perfecting the same practice with relative inexperience. A supportive culture of learning is important, and peer video reviews can be used throughout an organization.

For Teacher Preparation and Graduate Education Programs. At every stage of the career pipeline, educators need to develop interpersonal skills and reflective practice skills, both of which are exercised in the peer video review experience. Student teachers, leadership interns, and teachers in graduate programs or other forms of continuing study can and should engage in reflective communities of practice, and video peer coaching specifically facilitates on-the-job learning through sharing in an off-the-job setting. University faculty can model and facilitate video share discussion and growth among teachers (Arya, Christ, & Chui, 2014).

Recommendations for Future Study

Given the promise of peer video review, further study is needed to investigate the design, format, and contexts of successfully implemented video-sharing groups at the school and district levels in formal application, as well as via social media in more informal applications. While the use of clubs and video is gaining attention, their impact on practice needs further review, including the use of facilitators — trained and untrained, peer and nonpeer — in teacher video review sessions and the use of stock videos versus participants’ own recorded instruction (Beisiegel et al., 2018). The work of Beisiegel et al. warrants extension and further exploration. Gaudin and Chaliès (2015) suggest that video reviews should be integrated into teacher education courses and programs, and we suggest a study focus on best methods for accomplishing this charge.

Scholarly literature on teacher self-study and video review mentions the closely related concepts of teacher noticing and professional vision (Sherin & van Es, 2009; van Es & Sherin, 2008). These concepts may specifically be facilitated or enhanced through the introduction of the video medium in peer video reviews; thus, researchers might further inquire how teachers analyze their instruction, what they look for and notice, and what, if any, shifts in perspective occur regarding themselves and the experiences of their students.

Given the development of a sense of community in peer video review groups, it would be interesting to investigate the development of “meaningful bonds” (Knight et al., 2012, p. 21) over distance, when peer video reviews harness technology to facilitate sharing across wide geographic areas, connecting educators who may not necessarily share organizational connections within a school or district.

Also connected to technological enhancements, as found in our 2017 study (Kassner & Cassada, 2017), the integration of a backchannel into peer video review experiences helped facilitate real-time feedback and provided a written record for later reflection. Further inquiry is needed into the integration of such technologies and how they impact the experience of collaboration in formal and informal peer video review applications.

Another direction for research relates to ways in which video viewing can be brought to the local schools as part of in-service teachers’ continuing PD. Some researchers have suggested that teachers be trained as professional development facilitators or leaders to allow video viewing as a component of continuing professional development at the school and district level.

In discussions with practitioners and leadership in school districts in geographic proximity to our university, a need has been identified surrounding the development of teacher leaders who wish to enhance their skillsets and stay in the classroom, in contrast with teachers who aspire to administrative roles. Therefore, we intend to investigate potential partnership opportunities with a regional school district interested in building supportive cultures conducive to peer observation and exploring peer video review as a format for improving instructional practice and better preparing teachers for formal and informal instructional leadership roles.

References

Arya, P., Christ, T., & Chui, M. M. (2014). Facilitation and teacher behaviors: An analysis of literacy teachers’ video-case discussions. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(2), 111-127.

Beisiegel, M., Mitchell, R., & Hill, H. C. (2018). The design of video-based professional development: An exploratory experiment intended to identify effective features. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(1), 69-89. doi: 10.1177/0022487117705096.

Blakely, M. R. (2001). A survey of levels of supervisory support and maintenance of effects reported by educators involved in direct instruction implementations. Journal of Direct Instruction, 1(2), 73-83.

Borko, H., Jacobs, J., Eiteljorg, E., & Pittman, M. E. (2008). Video as a tool for fostering productive discussions in mathematics professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 417-436.

Cohen, C., & Rice, J. (2005). National Board Certification as professional development: Design and cost. Washington, DC: The Finance Project.

Concordia University. (2016, June 14). 10-year spending trends in U.S. education. Retrieved from http://education.cu-portland.edu/blog/news/10-year-spending-trends-in-u-s-education

Connor, C. (2017). Commentary on the special issue on instructional coaching models: Common elements of effective coaching models. Theory into Practice, 56(1), 78-83.

Daniels, E., Pirayoff, R., & Bessant, S. (2013). Using peer observation and collaboration to improve teaching practices. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 1(3), 268-274.

Danielson, C. (2007). Enhancing professional practice: A framework for teaching. (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: VASCD.

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017, June 5). Effective teacher PD. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/effective-teacher-professional-development-report

Desimone, L.M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Into Practice, 56(1), 3-12. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2016.1241947

DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (1998). Professional learning communities at work: Best practices for enhancing student achievement. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Forsythe, M., & Johnson, H. (2017). What to see, what to say: Tips for participating in teacher video clubs. Tools for Learning Schools, 20(2), 1-7.

Gaudin, C., & Chaliès, S. (2015). Video viewing in teacher education and professional development: A literature review. Educational Research Review, 16. 41-67.

Griffith, O. (2017, July 13). Knock-out teacher burn-out. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/owen-griffith/knockout-teacher-burnout_b_10819754.html

Governing the States and Localities. (2017). Education spending per student by state. Retrieved from http://www.governing.com/gov-data/education-data/state-education-spending-per-pupil-data.html

Gulamhussein, A. (2013). Teaching the teachers: Effective professional development in an era of high-stakes accountability. Retrieved from http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/teachingtheteachers

Holland, J. (2017, June 29). Why this effective and passionate teacher is leaving the classroom for now. [Web log comment]. Retrieved from https://www.teachingquality.org/why-this-effective-and-passionate-teacher-is-leaving-the-classroom-for-now/

Jones, H. J. (2015). The National Board Certification process as professional development: Perceptions about the impact that characteristics of the process had on professional growth (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from VCU Scholars Compass: scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3961/

Kassner, L. D. & Cassada, K. M. (2017). Chat it up: Backchanneling to promote reflective practice among in-service teachers. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 33(4), 160-168.

King, M. (2016). Six features of successful community practice. Journal of Staff Development, 37(6), 12-14.

Knight, J., Bradley, B. A., Hock, M., Skrtic, T. M., Brasseur-Hock, I., Clark, J., … & Hatton, C. (2012). Record, replay, reflect. The Learning Professional, 33(2), 18-23.

Learning Forward. (n.d.) Standards for professional learning: Quick reference guide. Retrieved from https://learningforward.org/docs/pdf/standardsreferenceguide.pdf

Learning Forward. (2015a). Standards for professional learning. Learning communities. Retrieved from https://learningforward.org/standards/learning-communities

Learning Forward. (2015b). Standards for professional learning. Learning designs. Retrieved from https://learningforward.org/standards/learning-designs

Learning Forward. (2015c). Standards for professional learning. Who we are. Retrieved from https://learningforward.org/who-we-are/purpose-beliefs-priorities

Miller, K., & Zhou, X. (2007). Learning from classroom video: What makes it compelling and what makes it hard. Retrieved from http://rcgd.isr.umich.edu/life/Readings2007/Miller%20video%20reading%201.pdf

Mizell, H. (2010). Why professional development matters. Retrieved from https://learningforward.org/docs/default-source/pdf/why_pd_matters_web.pdf

Moore, R. (2016, April 4). How do teachers (really) learn? Retrieved from http://inservice.ascd.org/how-do-teachers-really-learn/

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. (2017a). Get started. Retrieved from http://www.nbpts.org/national-board-certification/get-started/

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (2017b). Research. Retrieved from http://www.nbpts.org/research/

Nolan, J., & Hoover, L. (2011). Teacher supervision and evaluation: Theory into practice (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Pillars, W. (2014, May 20). Six signs of and solutions for teacher burnout. Center for Teacher Quality. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/tm/articles/2014/05/20/ctq-pillars-signs-of-solutions-for-burnout.html

Rosaen, C. L., Lundeberg, M., Cooper, M., Fritzen, A., & Terpstra, M. (2008). Noticing noticing: How does the investigation of video records change how teachers reflect on their experiences? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 347-360.

Sherin, M. G., & van Es, E. (2009). Effects of video club participation on teachers’ professional vision. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 20-37.

Sherin, M. G., & Han, S. Y. (2004). Teacher learning in the context of a video club. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 163-183.

Sterrett, W., Dikkers, A. G., & Parker, M. (2014). Using brief instructional video clips to foster communication, reflection, and collaboration in schools. Educational Forum, 78(3), 263-274.

Sterrett, W., Ongaga, K., & Parker, M. A. (2013). Developing collaborative professional growth through peer observations. Virginia Educational Leadership, 10(1), 38-53.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Swanson, K. (2014). Edcamp: Teachers take back professional development. Educational Leadership, 71(8), 36-40.

Tschannen-Moran, B., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2011). he coach and the evaluator. Educational Leadership, 69(2), 10-16.

van Es, E. A., & Sherin, M. (2008). Mathematics teachers’ “learning to notice” in the context of a video club. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(2), 244-276.

van Es, E. A., Tunney, J., Goldsmith, L. T., & Seago, N. (2014). A framework for the facilitation of teachers’ analysis of video. Journal of Teacher Education, (65)4, 340-356.

Vanderburg, M., & Stephens, D. (2010). The impact of literacy coaches: What teachers value and how teachers change. The Elementary School Journal, 11(1), 141–163.

Welman, P., & Bachkirova, T. (2010). The issue of power in the coaching relationship. In S. Palmer & A.McDowall (Eds.), The coaching relationship: Putting people first (pp. 139-158). London, UK: Routledge.

White, A. S., Howell Smith, M., Kunz, G. M., & Nugent, G. C. (2015). Active ingredients of instructional coaching: Developing a conceptual framework (R2Ed Working Paper No. 2015-3). Retrieved from http://r2ed.unl.edu

Wilson S. M., & Berne J. (1999). Teacher learning and the acquisition of professional knowledge: An examination of research on contemporary professional development. Review of Research in Education, 24, 173-209.

Wolpert-Gawron, H. (2016). The many roles of an instructional coach. Educational Leadership, 73(9), 56-60. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/jun16/vol73/num09/The-Many-Roles-of-an-Instructional-Coach.aspx

Appendix

(pdf download)

![]()