I felt that the learning style inventory was helpful in multiple ways. One way that it was helpful was if I hadn’t finished the reading, it would describe important concepts that would appear in the reading; so when I was reading, the concepts would catch my eye. Also, it went over important ideas: concepts, vocabulary, prior knowledge, basic skills, and steps. Besides important ideas and looking ahead, the learning style inventory also reviews important topics covered in previous class sections or readings. While working on the read-aloud lesson plan, it was helpful looking over the advice I had gotten from the learning style inventory. I felt somewhat confident in my finished product, but I felt I knew where to start, how to start, and what would come next. (Mara)

My first reaction to the learning style survey was not the greatest. I thought that this survey was just something to fill in. It was very interesting to look at the different learning styles and the advice that was given. After taking the survey several times, I found it easier and more helpful as the time went on. By being able to choose the learning style, each student was then able to relate to the material and advice given. The first time, I went through the survey I was pessimistic; I thought this could not help me in any way. Little did I know I would rely on this later. (Lacey)

These third year preservice teachers (all names are pseudonyms) in a reading methods course at a small midwestern U.S. university communicated their reactions to use of learning style information and an online module developed to scaffold students’ understanding of both learning styles and course content.

A Search for Improved Pedagogy to Increase Student Achievement

A real and ongoing challenge for teacher educators is how to make content accessible for all students. Reading methods courses for preservice teachers include content related both to theory and pedagogical practice. Instructors explain difficult concepts, model effective practices in the university classroom, and engage students in active learning (Komarraju & Karau, 2008; Lightner, Bober, & Willi, 2007, Meyers & Jones, 1993; Pentress, 2008; Struyven, Dochy, & Janssens, 2008) as ways to accommodate students’ needs and increase learning.

However, a number of factors may affect student performance in the course. Some students perform well in class but have difficulty with assignments that include multiple tasks outside of class. Others have difficulty transferring concept explanations provided in the classroom to independent tasks to be completed as assignments later. In addition, because of learning style preferences, some students prefer to listen to lectures in which theory is presented while others prefer concrete experiences. Others wish to observe, reflect, and then move to action. Students’ needs for support also differ.

Making content accessible or understandable for students points to the need for scaffolding. Teacher educators provide advice to students during office hours, addressing questions and providing clarification about assignments. They also reply to students’ inquiries when made via electronic mail or telephone. Advice is provided following the completion of assignments through written and oral feedback. Such advice may be specific to students’ learning styles, their performance in the course, and their understanding of course material.

These provisions of advice and feedback serve to scaffold course content to increase learning. Considering how to best meet the needs of all students in reading methods courses led to the research study described here. This research focused on increasing student achievement through increasing scaffolding, specifically through feedback linked to students’ learning style preferences.

Learning Styles and Learning Preferences

Honey and Mumford (1992, cited in Sabine Graf, Kinshuk, & Liu, 2009) described learning styles as “a description of the attitudes and behaviors which determine an individual’s preferred way of learning” (p. 3). Keefe (1985) noted that learning styles can be defined as “the composite of characteristic cognitive, affective, and physiological behaviors that serve as relatively stable indicators of how a learner perceives, interacts with, and responds to the learning environment” (p. 140).

Understanding characteristics of learning styles and students’ preferences allows instructors to plan experiences, integrate tools, and assess students in ways that match identified styles. Such alignment may provide access to learning by making content more understandable for particular students. Understanding learning styles may help instructors provide students multiple ways to learn and demonstrate their understanding of content and its application (Solvie & Kloek, 2007).

Several theorists (Kolb, Gardner, McCarthy, Honey & Mumford, Dunn & Dunn) have investigated and formulated models to represent and explain learning styles. Cognitive styles refer to how learners process information through thinking, remembering, and problem solving. Personality type models describe learners’ perceptions and approaches to tasks. Environmental models discuss characteristics of the learning context that promote or inhibit learning. Yet other learning style models focus on the abilities of learners themselves. A variety of models point to the multiple and varied factors that influence learning.

Research indicates that students learn best in ways that are consistent with their learning style preferences (Kolb, 1984, Larsen, 1992; Chen, Toh, & Ismail, 2005). Learning style theorist Kolb (1984) linked this phenomenon to the way in which disciplines relate to different styles of learning: “Thus, if students with a particular learning style choose a field whose knowledge structure is one that prizes and nurtures their style of learning, then accentuation of that approach to learning is likely to occur” (p. 164). This assertion applies in reverse as well. “The corollary to the accentuation process of development in which skills and environmental demands are increasingly matched is the alienation cycle that results when personal characteristics find no supportive environment to nurture them” (p. 166). Kolb further pointed out:

People enter learning situations with an already-developed learning style. Associated with this learning style will be some more or less explicit theory about how people learn, or more specifically, about how they themselves learn best. Learning environments that operate according to a learning theory that is dissimilar to a person’s preferred style of learning are likely to be rejected or resisted by that person. (p. 202)

Knowledge of learning styles may assist instructors as they introduce content and associated tasks in a particular field of study.

Kolb’s Model and Adaptive Flexibility in Learning Preferences

Kolb’s cognitive learning style model is the focus of this study because of its extensive research base on individual learning style preferences and because of the model’s application to classroom instruction. Because learners differ in their learning style preferences (see also Cartelli, 2006; Riding & Rayner, 2000), Kolb argued that addressing the needs of all learners demands attention to how learners both grasp and process information. In describing his cognitive learning style model, Kolb (1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2008) noted that students grasp information through concrete experience or reflective observation and process information through abstract conceptualization or active experimentation.

Kolb pointed to the importance of adaptive flexibility in terms of learning style preferences, noting the need to demonstrate ability to adapt to requirements of new positions, focusing on skills and abilities needed for such tasks. He wrote,

In making students more “well-rounded,” the aim is to develop the weaknesses in the students’ learning style to stimulate growth in their ability to learn from a variety of learning perspectives. Here, the goal is something more than making students’ learning styles adaptive for their particular career entry job. The aim is to make the student self-renewing and self-directed; to focus on integrative development where the person is highly developed in each of the four learning modes: active, reflective, abstract, and concrete. (p. 203)

Kolb illustrated how preferences become integrated, leading to increased learning:

In serving as the integrative link between dialectically opposed learning orientations, the common learning mode of any pair of elementary learning forms becomes more hierarchically integrated, thereby giving that learning orientation a greater measure of organization and control over the person’s experience. (p. 147)

Developing such a stance may be possible through first helping students understand the characteristics of their own preferred leaning style and how it might help and or stall them in successful completion of particular tasks.

Learning Style Preferences

Learning style preferences are identified through inventories much like surveys in which participants report information on how they prefer to learn and how they believe they learn best. The Kolb (2005) Learning Style Inventory asks learners to complete 12 sentences that describe their learning, ranking the choices from 1 to 4, which indicate how they learn best and are least like how they learn. Numerical responses are then totaled and graphed on what Kolb called a Cycle of Learning grid. Students record their scores along the vertical and horizontal lines that divide the circle or cycle into quadrants labeled Concrete Experience (CE), Reflective Observation (RO), Abstract Conceptualization (AC), and Active Experimentation (AE). The vertical axis extends from CE to AC, while the horizontal axis extends from AE to RO. However, learners’ scores seldom lie right on the axis of the cycle. In other words, learners are seldom entirely one or another when it comes to these preferences, but instead have preferences for more than one. While some learners have strong tendencies toward one learning style, they may also have preferences for other learning styles.

In addition, learners may prefer to have a concrete experience to begin the learning process (grasping) while another may prefer to read and think about material as the learning process begins. Similarly, some students may prefer to reflect as they process information while others may prefer to become actively involved and apply information during the processing period of the learning cycle. Because there are combinations of how students prefer to grasp and process in the learning cycle, Kolb identified four learning styles: Converger (grasp by AC and process through AC), Diverger (grasp by CE and process by RO), Assimilator (grasp by AC and process by RO), and Accommodator (grasp by CE and process by AE). Because each learning style is a combination of how learners prefer to grasp and process information, descriptors for these particular styles can be identified. These are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1

Kolb Learning Style Descriptors

| Assimilator | Accommodator | Converger | Diverger |

| Understands and creates theories. | Carries out plans and experiments. | Enjoys application of ideas. | Demonstrates creativity and imaginative ability. |

| Thinks through ideas. | Enjoys new experiences, is a risk taker. | Makes inferences from sensory experiences. | Views concrete situations from many perspectives. |

| Uses inductive reasoning. | Likes quick decisions and adaptations. | Likes situations with single correct answers. | Is a great brainstormer. |

| Synthesizes integrated ideas into a whole. | Solves problems in a trial and error manner. | Is unemotional. | Is interested in people. |

| Is less interested with people, more interested with abstract concepts. | Relies on others for information. | Deals with things rather than people. | Has a tendency to be emotional. |

| Needs to know what experts think. | Is interested in arts and humanities. | ||

| Is not interested so much IN theories, but whether or not they are sound and precise. | |||

| Critiques information and collects data. |

Kolb (2005) identified similar descriptors for the grasping (CE, AC) and processing preferences (RO, AE) which make up the learning styles. These descriptors are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2

Kolb Learning Style Preference Descriptors for Grasping and Processing Stages of the Learning Cycle

Grasping | Processing | ||

| Concrete Experience (CE) | Abstract Conceptualization (AC) | Reflective Observation (RO) | Active Experimentation (AE) |

| Prefers learning from experiences. | Enjoys logically analyzing ideas. | Makes decisions following careful observation. | Prefers to get things done. |

| Prefers to relate to people. | Prefers planning systematically. | Prefers to view issues from different perspectives. | Enjoys taking risks. |

| Is sensitive to feelings and people. | Makes decisions based on intellectual understanding of an idea. | Enjoys looking for the meaning of things. | Is able to influence people and events through action. |

Teacher Education and Learning Styles

“Making students aware of their learning styles and showing them their individual strengths and weaknesses can help students to understand why learning is sometimes difficult for them and is the basis for developing their weaknesses” (Sabine Graf et al., 2009, p. 3). Scaffolding as a way to help students understand concepts and issues that are specific to English education is important, since preservice teachers themselves will one day be working with elementary or secondary school students. Although research suggests that teachers use teaching styles that resemble their own preferred learning styles (Matthews & Jones, 1994), understanding their own learning style preferences and the need to address multiple learning styles may improve preservice teachers’ pedagogy. Pettigrew (1982, reported in Pettigrew & Buell, 2001) referred to this as “style expansion”—a “broad understanding of individual learning styles” (p. 187). Such an understanding will help future teachers identify and accommodate various learning styles (p. 189), a skill that is important with an increasingly diverse student population (Sloan, Daane, & Giesen, 2004).

Based on their study of preservice and in-service teachers’ attempts to identify the learning styles of their pupils, and this inaccurately, Pettigrew and Buell (2001) stressed that “educators must possess guided experiences to recognize student learning styles that include development of observational skills as well as use of formal diagnostic and assessment methods” (p. 189). Similarly, Matthews and Jones (1994) found that instructors at colleges and universities tended to reward with high grades teacher education students with the conceptual styles of learning and that prospective teachers clearly favored social and conceptual typologies. Since teaching style and learning style are closely related, these researchers noted that a large proportion of students in kindergarten through 12th grade “will be inadequately served unless the colleges of education accelerate attention to the responsibility for teaching to various learning styles” (p. 5). Sloan et al. (2004) noted that “if preservice teachers are made aware of how they learn best as well as how others learn best, they may not just teach to their own style of learning” (p. 11).

Scaffolding Content in English Education

Scaffolding or breaking skills into manageable steps or components, which was described by Vygotsky (1978; see also Collins, Brown, & Holum, 1991; Tilley & Callison, 2007), is followed by gradual release of responsibility to the learner. To make new or difficult material accessible to preservice teachers, scaffolding is used, “to remove limits gradually until they become more skillful” (Shih, Hung-Chang, Chang, & Kao, 2010, p. 82). Scaffolding also “refers to support that enables students to develop understandings that they would not have been capable of understanding independently” (Many, Dewberry, Taylor, & Coady, 2009, p. 148). Holton and Clarke (2006) defined scaffolding as “an act of teaching that (i) supports the immediate construction of knowledge by the learner; and (ii) provides the basis for the future independent learning of the individual” (p. 131).

Vygotsky (1978) noted the importance of a knowledgeable instructor guiding the learner through tasks they are not capable of completing on their own, leading to ability to complete tasks independently later. Scaffolding may take the form of modeling completion of tasks, structuring and identifying tasks for completion, providing advice as to next steps of task completion, providing feedback on progress or weaknesses to be addressed, or formal coaching practices (Collins et al., 1991). Thus scaffolding can take the form of coaching or provision of advice, a model used in this current study.

A number of research studies point to the effectiveness of using online or other technology tools to scaffold students’ understanding of course content. Shih et al. (2010) used scaffolding support successfully to develop independent learning skills among secondary students. A self-regulated learning system helped students with low self-regulated learning skills make significant improvement. Using a scaffolding theory adapted from Bruner to build learning patterns gradually, the system provided needed information and materials to students to help them determine their progress. On the instructor side, a Content Accessibility Subsystem was provided to organize learning materials. Ageli and Valanides (2004) used a similar model with primary student teachers to reduce cognitive load. Students in a control group were effectively guided in use of information and communication technology tools to help manage cognitive load when searching and organizing information from the Web.

Using the affordances of computer-based scaffolds significantly enhanced participants’ reflective journal writing and the length of written artifacts with novice teachers (Lai & Calandra, 2010). The researchers found that scaffolding may be one way to provide extra guidance to help novice teachers connect their experiences with knowledge about teaching. To provide this guidance, these researchers emphasized the importance of specific requirements conveyed in scaffolds, the structure of the scaffolds, and the use of critical incidents to anchor reflective journal writing. These findings are supported by the work of others who also used scaffolded experiences with computer-based technology to support instruction (Bean & Stevens, 2002; Chen & Bradshaw, 2007; Murray & McPherson, 2006; Roschelle et al., 2009).

Devereux and Wilson (2008) used course mapping to scaffold the literacy development of preservice teachers, finding that feedback is most helpful when it is constructive and timely and that a high degree of challenge with support in the how and what of each task can assist students in “becoming part of the discourse community of education” (p. 131).

Taback and Baumgartner (2004) helped preservice teachers learn the how and what of the inquiry process in science learning with scaffolding through partner structures with teachers. Similar to other scaffolding research with preservice teachers, they noted the importance of instructor feedback/advice to encourage and support students in the learning process.

Holton and Clarke (2004) in a research study on scaffolding and metacognition pointed to the importance of agency within the scaffolding process that “culminates in the students scaffolding their own learning” (p. 128). They argued that “the external dialogue of scaffolding becomes the inner dialogue of metacognition” (p. 131). They also indicated that scaffolding does not require the teacher and student to be physically present together (p. 131). This premise is advanced in this current study—helping students become aware of their learning style preferences, using advice linked to preferences to engage successfully with reading methods content, and using learning style preference information to guide approaches to future learning tasks.

Purpose of the Study

Based on research indicating a need for preservice teachers to understand their own and others’ learning preferences in order to create learning environments that better address the learning needs of elementary and secondary education students, this study was conducted to investigate how this might be done through scaffolding by coaching preservice reading methods students as they completed course assignments. Advice provided through coaching was based on students’ learning style preferences in an attempt to make prospective teachers aware of their own and other learning style preferences. This advice was linked to the knowledge base of the literacy and language methods course (Many, Dewberry, Taylor & Coady, 2004).

Research Questions

Research questions were as follows:

- How might technology tools be used to scaffold English education tasks by providing coaching to students?

- How will advice linked to learning style preferences affect student achievement in reading methods courses?

- How will advice linked to learning style preferences affect students’ understanding of their own and others’ learning style preferences?

Methodology

Context of the Study and Pedagogical Design

Six steps served as a framework for this current research:

- Complete task analysis of assignments.

- Prepare expert advice for four learning style preference groups aligned to assignment areas including concepts, key terms, prior knowledge, basic skills, and steps (task sequence).

- Create a web-based HTML program to serve as the access point for advice.

- Administer learning style inventories to students and identify learning style preferences.

- Provide students with the URL for advice links and feedback forms.

- Collect data, share data with students, and make use of data to inform learning and to revise/update advice.

A matrix was used to organize advice prepared for the four learning style preferences, CE, RO, AC, and AE. Advice for the selected assignments was also prepared.

The online module used to share advice was designed in the form of concept vines using a statistical model based on conditional dependence (Bedforde & Cooke, 2002, Solvie & Sungur, 2007). In other words, it required a nonlinear framework that would link students with particular advice based on responses provided to prompts about prior knowledge of concepts, possible sequence of assignment tasks, and approaches to task completion. Student responses were compared to expert rankings of the instructor, and advice was provided to students based on selections made within the module.

Students selected their learning style preference from a pulldown menu. Prompts within the module asked students to indicate their knowledge about concepts, key terms, prior knowledge, basic skills, and task sequence related to each assignment. General advice prepared for all students and specific advice aligned to learning style preferences was provided following students’ responses to prompts. In this way, advice presented through the online module was used to help students recognize expectations for task completion and how they might proceed with the tasks.

Table 3 provides an example of specific advice for CE, RO, AC, and AE learning style preferences. This task was part of Assignment 2, the reading and writing analysis of K-6 students’ reading progress. Advice from Table 3 was linked to learning style preference choices made by students on the learner side of the online module.

Table 3

Example of Preparation of Task Advice

CE | RO | AC | AE |

| As you complete this activity with the student be aware of two things—the oral responses andobservable behaviors. Look at the specific examples and analyze them from the three perspectives—cognitive, socio-cultural, and socio-linguistic. You will be doing this for two exercises as part of the assignment. (Look carefully for these two in the assignment rubric.) View this student as a unique case and pay careful attention to each response and to all behaviors. | You like to observe before making judgments. As you complete this activity with the student be aware of two things—the oral responses andobservable behaviors. Look at the specific examples and analyze them from the three perspectives— cognitive, socio-cultural, and socio-linguistic. Look carefully at what the literature says about these perspectives. Reflect on what the literature says in terms of what you have observed and recorded. You will be doing this for two exercises as part of the assignment. (Look carefully for these two in the assignment rubric.) | You enjoy theory. In this exercise you will be applying theory in a field experience. Look back at your course notes and in the research to review information on socio-cultural, socio-linguistic, and cognitive perspectives with regard to the student’s responses about reading. As you complete this activity with the student, be aware of two things—the oral responses andobservable behaviors. Look at the specific examples and analyze them from the three perspectives—cognitive, socio-cultural, and socio-linguistic. You will be doing this for two exercises as part of the assignment. (Look carefully for these two in the assignment rubric.) | In this exercise you will be applying theory in a field experience. Look back at your course notes and in the research to review information on socio-cultural, socio-linguistic, and cognitive perspectives with regard to the student’s responses about reading. As you complete this activity with the student be aware of two things—the oral responses andobservable behaviors. Look at the specific examples and analyze them from the three perspectives—cognitive, socio-cultural, and socio-linguistic. You will be doing this for two exercises as part of the assignment. (Look carefully for these two in the assignment rubric.) |

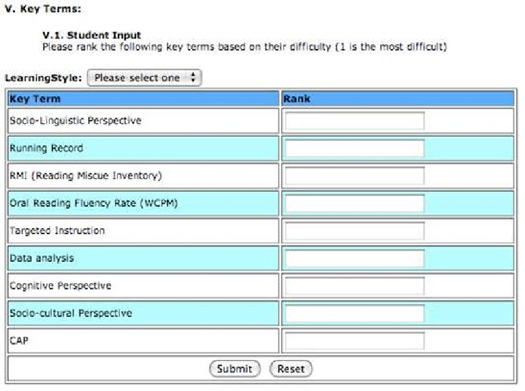

Figure 1 is an example of the key terms and the associated prompt within the advice module. It is an explanation of the key term and its relationship to the task. Advice linked to learning style preferences for key terms was general advice.

Figure 1. Key terms example in the learning style advice module.

Figure 1. Key terms example in the learning style advice module.

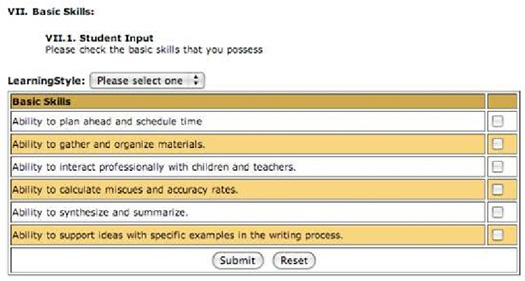

Figure 2 represents the basic skills portion of the learning style module. In this section of the module, students were prompted to indicate the skills they possessed that play an important role in their success with the assignment. Figure 3 displays advice provided to students with the reflective observation (RO) learning style preference.

Figure 2. Basic skills prompt.

Figure 2. Basic skills prompt.

Figure 3. RO advice linked to basic skills prompt.

Figure 3. RO advice linked to basic skills prompt.

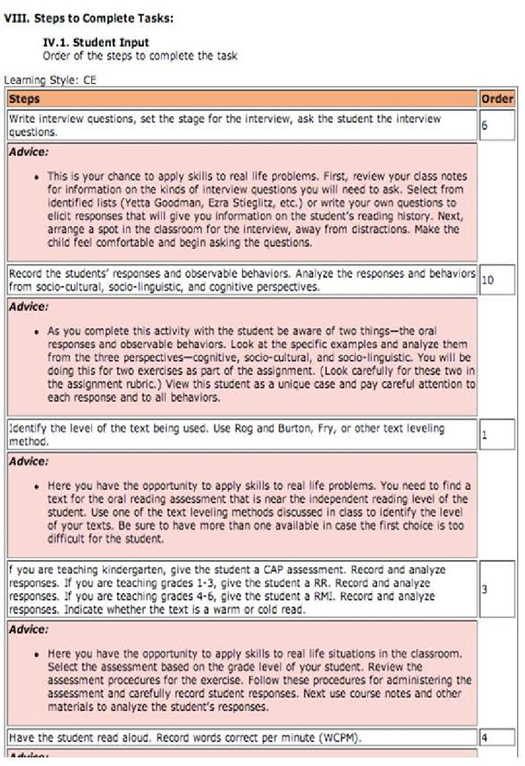

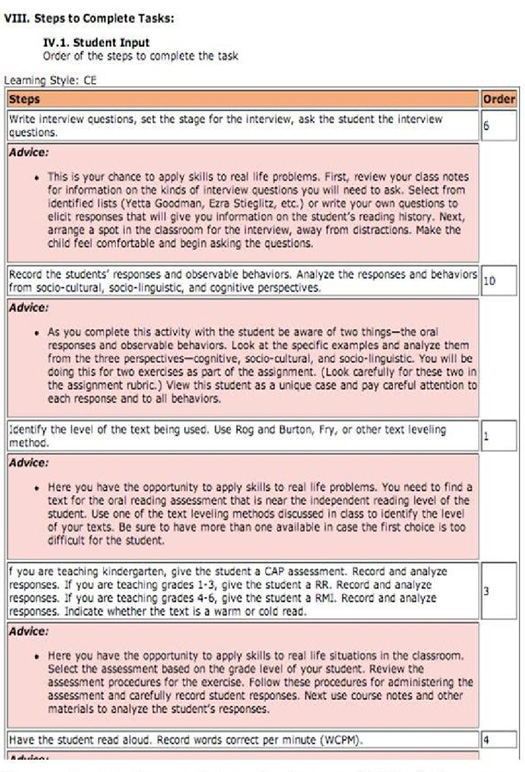

Figure 4 is an example of advice provided in the online module, this time for task sequence specific to the CE learner. Expert advice provided identifies preferred task sequence. Numbers indicate the order chosen by a student prior to receiving advice.

Figure 4. Advice module: Assignment 2 task sequence advice for reading methods students with the CE learning style preference.

Figure 4. Advice module: Assignment 2 task sequence advice for reading methods students with the CE learning style preference.

Students were asked to complete the module two times for each assignment. When the assignment was first introduced, students completed the module using their grasping learning style preference. When they had begun to work on the assignment, students completed the module again, this time using advice linked to their processing learning style preference in order to think about, use, and come to a deeper understanding of course content. Upon completion and submission of the assignment, students completed an assessment of their experience using the advice module. They also reflected on their experiences with the module following Assignments 1 and 3 using the journal tool in the course management system, Moodle. (See Appendix A.) The journal prompts for these assignments asked students to reflect on use of the advice module during both grasping and processing stages. The prompts asked,

- How did (or not) the learning style inventory activity help you grasp information on what was involved in this assignment? Did specific advice linked to your learning style help you? How?

- How did (or not) the learning style inventory activity help you process information on what was involved in this assignment? Did specific advice linked to your learning style help you? How?

Method

Participants

Participants in this research study that took place during fall semester were 28 students at a small liberal arts college in the midwest section of the United States. Participants were preservice teachers in a third-year reading methods course. Of the 28 total students 3 were male and 25 were female. Five were first generation college students. The ethnic makeup of the class included 4 American Indian students, 2 Asian students, 1 Hispanic student, and 21 Caucasian students. All students consented to participate in this study. On the first day of the 16-week course, students completed a Kolb (2005) Learning Style Inventory to identify individual learning style preferences. Scores for both grasping (CE, AC) and processing (RO, AE) were identified. While students had scores across all four learning style preferences, students’ highest scores for the grasping stage and their highest scores for the processing stage were recorded. If the scores for preferences were the same, both were recorded (N = 1).

To provide advice, the online module was designed using coaching techniques to scaffold difficult content and address students’ learning style preferences. Advice provided within the coaching process made use of Kolb’s learning style preference descriptors. Though advice was provided and its use encouraged, students could choose whether or not to access and use the advice.

The learning style advice module had an instructor side and a learner side. Expert advice for learning style preferences and assignment concepts and tasks was prepared and entered into the module on the instructor side. The prepared advice was then linked to learning style preferences and responses to prompts within the module.

Advice presented through the module was used to help students recognize effective approaches to assignment tasks and application of course content. When tasks did not align with their preferences, advice included information on their preferences along with suggestions for moving toward actions that would help them be successful. Advice to a preservice teacher with a high reflective observation score, as noted in the example presented earlier, was as follows:

You like to observe before making judgments. As you complete this activity with the student, be aware of two things—the oral responses and observable behaviors. Look at the specific examples and analyze them from the three perspectives—cognitive, socio-cultural, and socio-linguistic. Look carefully at what the literature says about these perspectives. Reflect on what the literature says in terms of what you have observed and recorded. You will be doing this for two exercises as part of the assignment.

The assignments for the reading methods course included one near the beginning, in the middle, and near the end of the course. The assignments focused on lesson plan development, analysis of reading and writing development in K-6 students, and knowledge of approaches to reading instruction as demonstrated through professional collaboration in a wiki environment.

The research targeted four university learning outcomes: (a) students can identify, define, and solve problems, (b) students can locate and critically evaluate information, (c) students have mastered a body of knowledge and a mode of inquiry, and (d) students have acquired skills for life-long learning.

Research Design

A mixed methods research design was used for the project. Mixed methods makes use of both quantitative and qualitative data to understand the results of a research study. Greene and Caracilli (1997) identified the benefits of mixed methods research, including triangulation of findings; complementarity, in which results of one method serve to clarify or illustrate results of another method; development, with one method serving to shape or define steps taken in another method; initiation, in which results of one method may point to the need for further examination in particular areas; and expansion, in which the combination of methods provides detail that may have been absent without the use of more than one method. Mixed methods may lead to increased quality and scope of a research study prompted by critical analysis of data from multiple perspectives.

Quantitative data in this study included student assessment results from the learning style preference advice module and students’ assignment scores. Qualitative data included students’ reflection journal responses following use of the advice module.

Analysis of Data

Data from this research study were first of all analyzed to learn whether or not the learning style preference module assisted preservice teachers in understanding course content. Scores from assignments were compared to scores from preservice teachers who did not make use of the learning style module. (Data from a control group—students in the previous course with no advice—was compared to the experimental group that was provided advice in this study.) In addition, self-report data collected throughout the study from the learning style preference module was coded for three categories: whether or not students followed the advice, usefulness of the advice, and overall difficulty of the assignment (n = 54 responses). Last, qualitative comments from students following completion of two assignments and reported on Moodle were analyzed using grounded theory (Glasser & Straus, 1967). Line-by-line coding was completed followed by identification of action codes, which were, in turn, followed by identification of themes within the data.

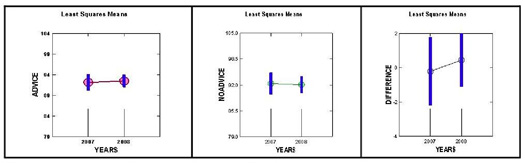

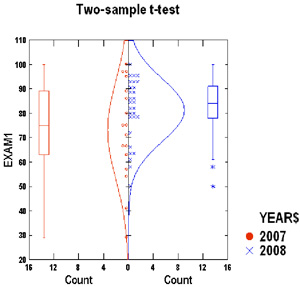

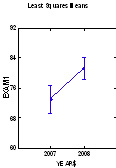

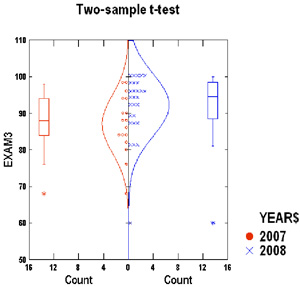

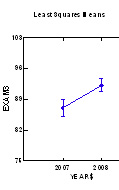

Results from Assignment Scores

Using Least Square Means assessment and data from a control group (students completing the assignment in the previous course with no advice) for comparison, a slight increase was found on students’ performance on the assignments with advice and a slight decrease in students’ performance on the assignments with no advice, as noted in Figure 5. The increase in students’ performance was not statistically significant.

Figure 5. Assignment comparison: Advice, No Advice.

Figure 5. Assignment comparison: Advice, No Advice.

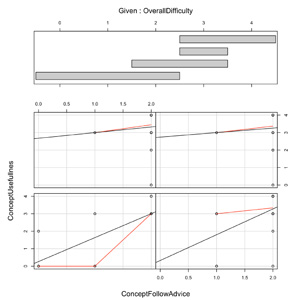

Results from Self-Report Data

Organization and selection of the prompts within the advice module were as important as were correlations to the learning style preferences. Within the learning process, understanding of concepts central to the assignment, knowledge of key terms, prior knowledge, and knowledge of task sequence affect performance resulting in successful completion of assignments. Based on these principles, prompts solicited information about students’ understanding of concepts central to the assignment, important terms, prior knowledge, basic skills needed for task completion, and task sequence. Once students responded to prompts—by ranking (for task sequence), indicating their comfort level (with prior knowledge information), and checking basic skills possessed—advice was provided. Advice varied and was delivered based on learning style preference characteristics and students’ responses to prompts.

When students had a difficult time with assignments, whether they used the concept advice or not, they responded that the advice was useful. However, when they believed the assignments were easy, regardless of whether they followed the concept advice or not, they responded that the advice was not useful.

Whether or not they believed the assignments were difficult, if they followed the task sequence advice, then it was useful for them. Regardless of whether or not they thought the assignments were difficult, if they followed the prior knowledge advice, then it was useful for them. Overall students’ responses in this assessment related to usefulness of the module (N = 76) and usability (N = 18) of the advice module. (See Figure 6)

Figure 6. Usefulness of advice plots.

Figure 6. Usefulness of advice plots.

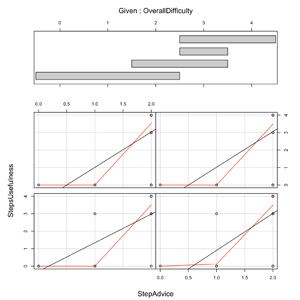

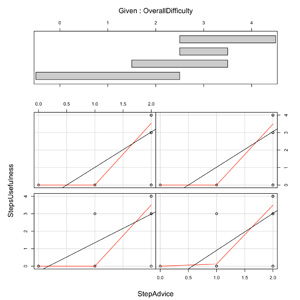

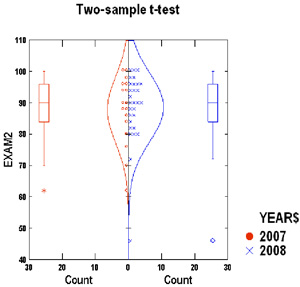

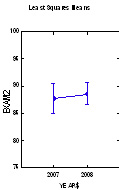

In addition to students’ beliefs regarding usefulness of the advice, students’ performance in the course, as identified on three course assignments and three course exams, was analyzed using least squares means. Results of assignment performance indicated a slight decrease for Assignments 1 and 2 (lesson plan development and the reading and writing analysis) but a statistically significant increase for Assignment 3 (the wiki assignment). For the reading methods students, results showed there was no significant increase for Exam 1 related to Assignment 1, (p-value: 0.10), no significant change for Exam 2 related to Assignment 2 (p-value: 0.813), and an overall statistically significant increase on students’ performance for Exam 3 related to Assignment 3. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7. Exam performance results.

Figure 7. Exam performance results.

Narrative Comments on Students’ Use of the Tool

Additional qualitative comments about the learning style advice module collected via the journal tool within the course management tool Moodle were also analyzed. This analysis was done using constant comparative analysis (Glasser & Strauss, 1967). Interrater reliability was 91%. Line-by-line coding was used, first to identify emerging categories within the data and then to refine the emerging categories. Line-by-line coding of data resulted in eight codes: kind of experience, set up of the module, quality of advice, outcome of the experience, consideration of assignment completion, consideration of personal learning, consideration of pedagogical skills for application, and demonstration of pedagogical knowledge. From these initial categories, two major themes were identified, these being advice presented in the module and completion of assignment tasks. These themes were reflected in frequency of responses.

Most students responded positively to use of the module by indicating that they liked the module, that it was a great experience, and that it was helpful. Fewer students responded in the negative, indicating that they felt clueless, that the module was boring, and that the module was somewhat helpful. In response to the set up of the module, students indicated they liked particular components of the module such as the definitions, steps, and the way in which it drew their attention to details they might have otherwise missed. Some students expressed that they liked choosing their learning style preference and receiving advice linked to it. One student wrote, “It opened my eyes into what all was needed to do and in what order things needed to be done in order to have an appropriate reading lesson.” Some expressed feeling lost in the module and that they did not understand its purpose.

Concerning the quality of the advice provided within the module, most of the students stated that the feedback and advice was immediate and helped them to think about learning styles and the tasks at hand. Many students commented on how the explanations with the module served to clarify information, correct misconceptions, and or remind them of what needed to be done. One student wrote, “I liked that right away after you provide your answers the program provided feedback.” Another student felt confident of knowing the strategy already and did not need the advice, while another indicated, “It was nice to look at some of the advice and say oh, I actually knew that!”

Students indicated that after using the module, they were more familiar with the terms and it helped them understand the process of preparing read-aloud lessons and completing a reading and writing analysis. Students also believed the module helped with review of course content. One student wrote, “There were times I would purposely make mistakes just to get the advice and have a review,” and another wrote, “The inventory did force me to slow down and really think about the components that we were discussing.”

Relating to the outcome of the experience, students indicated that after using the module they had a better understanding of the terms they had found difficult. Others noted that they comprehended more, that the information seemed to stick, and that they felt more confident after using the module. One student indicated that the module helped them slow down and break the assignment into parts; another wrote, “Looking back, I think I could have used it even more.”

Student feedback indicates that taking the inventory a second time was easier for students since they had used the online module previously. Perhaps more importantly, advice provided based on their learning style preferences about concepts, terms, and task sequence helped students develop deeper understanding of the concepts, terms, and task sequence related to assignments.

Some students indicated they knew what they needed to spend more time on and what they “needed to do to become better.” A student wrote, “I felt that the module made some parts of what we learned stick better.” Another indicated, “It reassured me that I knew the material.” Others wrote, “After the second time of taking the inventory, I enjoyed it a bit more,” and “The second time I did the inventory, I felt that I knew a little bit more about the process.” Another indicated that doing the assignment facilitated learning more than following the advice did.

Looking closely at the responses that related to the final three themes presented interesting results. Students’ responses did not pertain to consideration of their own personal learning, consideration of how they might apply pedagogical practices, or even demonstration of knowledge of pedagogical practices in English education. Instead, their responses related to how the module helped them complete course assignments.

For the most part, students’ focus as expressed in their responses was on completion of the assignment. Multiple responses pointed to specifics of the tasks needed to complete the assignment successfully. Students wrote,

- “I thought that this learning style inventory was helpful in understanding what should be included in the lesson plan and the steps that needed to be taken to create the lesson plan.”

- “…I felt I knew where to start, how to start, and what would come next.”

- “This served as a study guide for me in a way.”

- “I really think about the components we have been discussing.”

For the most part, students’ reactions to use of the advice module evidenced change in terms of understanding the assignment expectations and how they might successfully complete the assignments. The following are examples of growth in understanding more about their own learning processes or how the advice module served as a scaffold for their learning.

The advice was given clearly and seemed to be very helpful. I now believe that I can do a writing analysis by heart because of the advice given. There were times where I would purposely make mistakes just to get the advice and to have a review. I know the order but I would mess it up just enough so I would be able to have a little review session myself.

I enjoyed the technological components of my reading methods course. Looking back on the time spent, I realize that these projects will help me in the future. The learning styles survey made me think about the differences of students as well as how they learn. I was told that it takes about 8 times for a student to actually remember a term and with this survey and the advice given, I remember it!

Other related comments included, “It was nice to get some advice…and see what my strengths and weaknesses were in what we have been working on,” and “It showed me a few things about myself.”

Recognition and use of learning style information to increase students’ comprehension and utilization of content for future learning experiences and in future teaching context, as expressed by these students, was an outcome expressed by few of the students. No students considered scaffolding in their responses. (See Appendix A for all of the student comments.)

Conclusion: Recommendations, Implications, and Plans for the Future

Overall, data analysis results for this research study point to the value of a learning style preference advice module as a scaffolding tool. Students’ assessment results when advice was provided were higher than when advice was not provided. Also, students believed the online module provided valuable information in understanding and applying content to the completion of course assignments. Scaffolding through coaching was possible using the advice module. Feedback to students was targeted and timely.

Analysis of quantitative data did not result in significant differences for Assignments 1 and 2, but did indicate a significant difference for Assignment 3 and the associated assessment between students who received advice and those who did not. This difference may be due to students’ use of the module multiple times at this point in the study. It could also be due to increasing familiarity with information in the field of reading methods and integration of that information at that point in the course. These factors were not controlled for in this study.

The process of creating and using an advice module linked to learning style preferences, as was done in this study, may serve as a model for others who would like to scaffold the work of preservice teachers. The advice module also serves as a model of providing feedback for assignments when students may be reluctant or not feel the need to talk with a course instructor. Most importantly, the module is an example of how feedback can be prepared and used to support the learning of students with multiple and varied learning style preferences.

The findings of this research point to the value of providing feedback based on learning style preferences. Coupled with feedback provided to students in other ways throughout the course, the online learning style preference module adds additional support to preservice teachers that may lead to increasing their understanding of course content and learning styles. Additional research on assisting students in understanding connections between their learning style preferences, course content, and expectations of course assignments may lead to application of learning style preference information in other learning experiences in which preservice teachers engage. It may also lead to improved pedagogical practices as teachers teach more intentionally to a variety of learning styles in their own classrooms.

Although a few students in this study said they became more aware of their learning style preferences, and to some extent the need for flexibility when approaching tasks, an important finding of this study was that few students expressed an understanding of learning styles in a way that helped them understand their own learning and how this information could assist them with learning tasks outside the reading methods course. Instead, students’ attention was focused on completion of assignments and without consideration of further application beyond the assignment. This response raises concerns for how preservice teachers in the reading methods course are transferring information to further learning contexts, including how they might transfer information and experiences to future pedagogical situations.

Results of this study point to the need to assist students in moving a focus that had been solely on successful completion of course assignments to using the experience of the assignment to (a) consider their own learning strengths and areas of weakness and (b) to consider how assignment experiences can be transferred to pedagogical practice. In other words, how might instructors help students move toward a more holistic understanding of teaching and learning as a result of the assignments that are a part of English education courses? How might instructors assist students with their own learning processes while at the same time preparing them to be teachers?

More explicit instruction may be needed to help students make these connections. Explicit instruction around scaffolding may also be necessary to follow up on the recommendations of Holton and Clarke (2006). These researchers noted, “Because the scaffolding of knowledge is a vital aspect of learning, it is important that learners become aware of the scaffolding process. This process can then be internalized for future use so that knowledge can be built or problems solved without the assistance of the teacher” (p. 131).

Limitations within this study include the small sample size used. There were also some challenges in preparing the advice module due to time required to write advice to be uploaded to the advice module for four learning style preferences. However, once advice is written, it can be revised and updated as needed over time.

Building on the initial success of this learning style preference module, plans for the future include modification of the online module in order to recognize students and their preferred learning style preferences when they log into the module, creation of a mechanism to sort data by learning style preference within the module, and changes leading to a user friendly reflection tool for use by students for articulation of skills learned. Using feedback for tasks and advice provided by student participants, the advice module will be modified and updated for future use and ongoing study.

Using the results of this study, additional emphasis will be placed on explicit instruction in learning styles and scaffolding. This emphasis will include assisting students in making use of learning style preference information not only in relation to completion of course assignments, but also to use of information in setting learning goals to guide personal learning. In addition, an emphasis will be placed on helping students recognize that assignments are not ends in themselves but are purposeful and meaningful in terms of understanding and applying effective pedagogical practices in English education.

References

Angeli, C., & Valanides, N. (2004). The effect of electronic scaffolding for technology integration on perceived task effort and confidence of primary student teachers. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 37, 29-43.

Bean, T., & Stevens, L. P. (2002). Scaffolding reflection for preservice and inservice teachers. Reflective Practice, 3(2), 205-218.

Bedford, T., & Cooke, R. M. (2002). Vines: A new graphical model for dependent random variables. The Annals of Statistics, 30, 1031-1068.

Cartelli, A. (Ed.). (2006). Teaching in the Knowledge Society: New skills and instruments for teachers. Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishers.

Chen, C., & Bradshaw, A. (2007). The effect of web-based question prompts on scaffolding knowledge integration and ill-structured problem solving. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 39(4), 359-375.

Chen, C., Toh, S., & Ismail, W. (2005). Are learning styles relevant to virtual reality? Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 38(2),123-141.

Collins, A., Brown, J.S., & Holum, A. (1991). Cognitive apprenticeship: Making thinking visible. American Educator. Retrieved from the 21st Century Learning Initiative Archive: http://www.21learn.org/site/archive/cognitive-apprenticeship-making-thinking-visible/

Devereux, L., & Wilson, K. (2008). Scaffolding literacies across the bachelor of education program: An argument for a course-wide approach. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 36(2), 121-134.

Ertekin, E., Dilmac, B., & Yazici, E. (2009). The relationship between mathematics anxiety and learning styles of preservice mathematics teachers. Social Behavior and Personality, 37(9), 1187-1196.

Glasser, B.G., & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Greene, J. C., & Caracelli, V. J. (1997). Defining and describing the paradigm issue in mixed-method evaluation. In J. C. Greene & V. J. Caracelli (Eds.). Advances in mixed-method evaluation: The challenges and benefits of integrating diverse paradigms: New directions for program evaluation (Vol. 74, pp. 5-18). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Holton, D., & Clarke, D. (2006). Scaffolding and metacognition. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 37(2), 127-143.

Keefe, J. (1985). Assessment of learning style variables: The NASSP Task Force Model. Theory Into Practice, 24(2), 138-144.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Kolb, D. A. (2005). The Kolb learning style inventory. Boston, MA: Hay Resources Direct.

Kolb, D., & Kolb, A. (2008). Experiential learning theory: A dynamic, holistic approach to management of learning, education and development. In S. J. Armstrong, & C. Fukami, (Eds.), Handbook of management learning, education and development. London, England: Sage Publications.

Komarraju, M., & Karau, S. J. (2008). Relationships between the perceived value of instructional techniques and academic motivation. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 35, 70-82.

Lai, G., & Calandra, B. (2010). Examining the effects of computer-based scaffolds on novice teachers’ reflective journal writing. Educational Technology & Development, 58, 421-437.

Larsen, R. E. (1992). Relationship of learning style to the effectiveness and acceptance of interactive video instruction. Journal of Computer-Based Instruction, 19, 17-21.

Laske, O. (2004). Can evidence based coaching increase ROI? International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 2(2), 41.

Lightner, S., Bober, M., & Willi, C. (2007). Team-based activities to promote engaged learning. College Teaching, 55, 5-18.

Many, J., Dewberry, D., Taylor, D.L., & Coady, K. (2009). Profiles of three preservice ESOL teachers’ development of instructional scaffolding. Reading Psychology, 30, 148-174.

Matthews, D., & Jones, M. (1994). An investigation of the learning styles of students in teacher education programs. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 21(3),234-246.

Meyers, C., & Jones, T.B. (1993). Promoting active learning: Strategies for the college classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Murray, D., & McPherson, P. (2006). Scaffolding instruction for reading the Web. Language Teaching Research, 10(2), 131-156.

Pentress, K. (2008). What is meant by active learning? Education, 128(4), 566-569.

Pettigrew, F., & Buell, C. (1989). Preservice and experienced teachers’ ability to diagnose learning styles. Journal of Educational Research, 82(3), 187-189.

Riding, R. J., & Rayner, S. G. (Eds.). (2000). Cognitive styles. Stamford, CT: Ablex Pub. Corp.

Roschelle, J., Rafanan, K., Bhanot, R., Estrella, G., Penuel, B., Nussbaum, M., & Claro, S. (2010). Scaffolding group explanation and feedback with handheld technology: Impact on students’ mathematics learning. Education Tech Research & Development, 58, 399-419.

Sabine Graf, K., & Lieu, T. (2009). Supporting teachers in identifying students’ learning styles in learning management systems: An automatic student modeling approach. Educational Technology & Society, 12(4),3-14.

Shih, K., Hung-Chang, C., Chang, C., & Kao, T. (2010). The development and implementation of scaffolding-based self-regulated learning system for e/m-learning. Educational Technology & Society, 13(1), 80-93.

Sloan, T., Daane, C.J., & Giesen, J. (2004). Learning styles of elementary preservice teachers. College Student Journal, 38(3), 494-500.

Solvie, P., & Kloek, M. (2007). Using technology tools to engage students with multiple learning styles in a constructivist learning environment. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 7. Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol7/iss2/languagearts/article1.cfm

Solvie, P., & Sungur, E. (2007). The use of concept maps/graphs/trees/vines in the instructional process. World Scientific Engineering Society and Academy Transactions on Communications, 6, 241-249.

Struyven, K., Dochy, F., & Janssens, S. (2008). Students’ likes and dislikes regarding student-activating and lecture-based educational settings: Consequences for students’ perceptions of the learning environment, student learning and performance. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 23(3), 295-317.

Tabak, I., & Baumgartner, E. (2004). The teacher as partner: Exploring participant structures, symmetry, and identity work in scaffolding. Cognition and Instruction, 22(4), 393-429.

Tilley, C., & Callison, D. (2007). New mentors for new media: Harnessing the instructional potential of cognitive apprenticeships. Knowledge Quest/Assessing Information and Communication Technology, 35(5), 26-31.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds. & Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original work published in 1934).

Author Information

Pamela Solvie

Northwestern College

email: [email protected]

Engin Sungur

University of Minnesota, Morris

email: [email protected]

Appendix A

Students’ Qualitative Statements on Use of the Learning Style Module for

Assignments 1 and 3 by Student Number

Students’ Qualitative Statements on Use of the Learning Style Module for Assignment 1 | |||

Student Number | Grasping Learning Style Preference | Processing Learning Style Preference | Student Statements |

1 | AC, CE | RO | No statement |

2 | AC | RO | My experience with the learning style inventory was good. The first time I completed it I received a lot of advice, and the second time I did it I felt that I knew a little bit more about the process. Although I felt that I improved my knowledge from the first time to the second time and tried to follow the advice that was given, at times I felt lost while writing my lesson plan. I thought that this learning style inventory was helpful in understanding what should be included in the lesson plan and the steps that needed to be taken to create the lesson plan. Also, I thought it was useful that the terms that I found difficult were defined because I think it gave me a better understanding. I am glad I did the learning style inventory twice because I think I grasped the information better. Overall, I thought this inventory was very useful. |

3 | CE | AE | I have had a pretty positive experience with the learning style inventory. I don’t know exactly what all of the information given was about, but I learned that I need to try and cooperate all of the learning styles into my lesson. I need to account for more of the styles when thinking about what I will be teaching. I learned that I need to think that all lessons are important because when doing the inventory, I just pushed some of the styles away because I thought they were less important. I now know that all of styles are important for proper instruction. |

4 | AC | AE | After doing the learning style inventory I would have to say that I enjoyed the advice that it gave me to my responses. I felt that over all they were helpful. I learned a lot about portions of the reading system that I was unsure on. It was nice to get some advice in writing and see what my strengths and weaknesses were in what we have been working on. It was also nice to look at some of the advice it gave and say “oh, I actually knew that!” I felt it made some parts of what we learned stick a little better because we actually had to apply them to something. Sometimes I thought that it was unclear what portions of what I addressed needed to be changed. This was especially clear in the ranking portions when I believe there was supposed to be a specific order to it but I was unsure what the end order was. If this was better defined I think it would have made the advice it gave with each more helpful. If the order didn’t actually matter I thought that was a little unclear. |

5 | AC | RO | I liked the learning style inventory but I think it could have been explained better. The first time I took it I didn’t understand that it was supposed to help us write our lessons so I don’t think I got a lot of benefit from it. The second time I understood what it was getting at and read the advice and it helped some. I was still confused about the lesson plans, however the feedback was nice. |

6 | AC | RO | No statement |

7 | AC | AE | The learning style inventory was very helpful in reviewing key concepts about a read-aloud lesson plan according to my learning styles AE and AC. As of now, I know that a read-aloud lesson is one of the four components of a balanced reading program. I also know that read-alouds provide the most support or scaffolding for students, for the teacher is doing most of the reading. I am even aware of the other components in a balanced framework, which include shared reading, guided reading, and independent reading. |

8 | CE | AE | I thought that the learning style inventory was really interesting and neat! I liked that right away after you provided your answers the program provided feedback. I thought it was really helpful, I actually went and looked some things up in our book to make sure I understood them. I liked the question that gave feedback on things that it thought about your personality (sort of). I liked doing the learning style inventory because it showed me a few things about myself and prompted me to think about some things that I would not have thought of on my own! |

9 | CE | AE | The first learning style inventory did not help me at all because i did not understand that we were to use it to help us plan our read aloud lesson plan. In the end though the advice in the second learning style inventory really helped me understand how important read aloud strategies are to help the children learn how to become a good reader. I used the advice I got from the learning style inventory to help me write my read aloud and shared reading lesson plans. |

10 | AC | AE | No statement |

11 | AC | RO | I felt that the learning style inventory was helpful in multiple ways. One way that it was helpful was if I hadn’t finished the reading, it would describe important concepts that would appear in the reading; so when I was reading the concepts would catch my eye. Also, it went over important ideas: concepts, vocabulary, prior knowledge, basic skills, and steps. Besides important ideas and looking ahead, the learning style inventory also reviews important topics covered in previous class sections or readings. While working on the read-aloud lesson plan, it was helpful looking over the advice I had gotten from the learning style inventory. I felt somewhat confident in my finished product, but I felt I knew where to start, how to start, and what would come next. For example, one needs to think of a strategy before writing the objectives. All in all, I felt that the learning style inventory had great advice to help with the mini-lesson and introduce and review important concepts that will come up time and time again. |

12 | CE | AE | This was great to get this started. I know now what it takes to complete a mini-lesson. I know what to expect and what things I need more clarification on. |

13 | AC | RO | My experience with the learning style inventory was that I found it useful because it filled me in on how steps should be ordered, and reassured me that I knew the material. It really caused me to think about what was being asked, and because of that, I feel I comprehended the information being presented to be very well. It acted like a summary in a way of all the information I have learned up until this point, so it was great to see a different organization of the material learned. I liked that we also got to choose our learning style because it helped me to understand how I learn, and focus on areas I may need some more work. |

14 | AC | AE | No statement |

15 | AC | RO | No statement |

16 | CE | AE | I did the learning style inventory and the entire time I felt as if I was ‘clueless’. The great thing about the inventory is that it gave great feedback to all of my responses which was very helpful in planning my read aloud lesson. |

17 | AC | AE | No statement |

18 | AC | AE | No statement |

19 | CE | AE | No statement |

20 | CE | AE | I felt that most of the advice was somewhat useful. I found that after reading some of the advice, I already knew the things that were said, I just hadn’t made the connections at the time of answering the question. One thing that the inventory did do was force me to slow down and really think about the components that we were discussing. It was interesting to do so while in the midst of planning my lesson. I was reminded of the items that I was neglecting to think about. The other thing that it did for me was to confirm that I was doing okay. It was nice to have that confirmation because sometimes it feels like I don’t know what I’m doing at all! |

21 | CE | AE | No statement |

22 | CE | RO | I didn’t feel like it helped me at all. I felt like it was unclear as to why I was doing it, so I just did it for the sake of doing it. I looked back at it a third time to refresh my memory about what I actually did do and I thought about it and still didn’t think that the information could have been very helpful to me. It made a little more sense when I looked at it the second time, but I still did not understand the purpose. After talking to my classmates today and yesterday they were unaware of the purpose also until it was explained by a student that had talked to you about it. |

23 | AC | RO | No statement |

24 | CE | AE | I have enjoyed doing the learning style inventory. It has given me the chance to review the things that I was not fully understanding. It has helped me also to organize my reading lessons and the order and reasons for the order in assessing my reading students. It is interesting then to try it with a different learning style. I enjoy trying it out a few times more to see if I have improved in knowing some areas better. It is difficult to remember to do it online and maybe takes a few reminders to do it. |

25 | AC | AE | I thought the learning style inventory was interesting and provided some good informational feedback. It made me actually come to terms with what I feel comfortable with and what I don’t feel comfortable with. The information that came up after the submission of your answers was helpful and gave a sense of direction to me because on some of the questions like the ones where we had to rank in order of importance or level of difficulty I was very off and after reading the information it helped me grasp the concept why some have a higher level of difficulty or level of importance. The information that was given after the submission was generally brief and to the point which I found pleasing. After taking this inventory it gave me an idea on what I need to work on to become better. |

26 | CE | AE | No statement |

27 | AC | RO | At first I thought this was kind of boring, and I didn’t really get what we were supposed to do, but I tried my best and did it as I thought it should be done. The second time that I did this, I understood it better and we had more class time to soak in the information and I think I did really well on the inventory this time. It opened my eyes into what was all needed to do and in what orders things needed to be done in order to have an appropriate reading lesson. After the second time of taking it, I enjoyed it a bit more. |

28 | AC | RO | No statement |

| Students’ Qualitative Statements on Use of the Learning Style Module for Assignment 3 | |||

Student Number | Grasping Learning Style Preference | Processing Learning Style Preference | Student Statements |

1 | AC, CE | RO | The learning style inventory was somewhat helpful when I was working on the reading and writing analysis. I found the guidelines for the steps of the process helpful in guiding me while I was doing the assignment. I didn’t really find the specific advice linked to my learning style any more helpful. |

2 | AC | RO | No statement |

3 | CE | AE | No statement |

4 | AC | AE | No statement |

5 | AC | RO | The learning style inventory helped me grasp the information on what was involved in the reading and writing analysis. I’m not sure that it was necessary that the advice was specifically linked to my learning style. The advice helped to clarify what specific terms meant and the steps that I needed to complete to finish my analysis. The advice was the most helpful in clarifying terms like cognitive perspective, socio-cultural perspective and socio-linguistic perspective. I was very unclear about those before the learning style inventory. The learning style helped me process what was involved in the reading and writing assignment. It is nice to be able to see things more than once since then you can start picking up on the meaning more. Again I think any advice would have been helpful and that it didn’t specifically need to relate to my particular learning style. |

6 | AC | RO | No statement |

7 | AC | AE | I feel that the learning style inventory activity helped me grasp information prior to starting my reading and writing analysis assignment. I did not know that information could be looked at from three different perspectives. Also, I did not know how to analyze from a socio-cultural, socio-linguistic, or a cognitive perspective because I did not know what these terms meant. However, I learned what each term meant, for the inventory defined all three perspectives for me. I now know that socio-cultural refers to the use of language based on traditions, cultural events, and understandings of power relationships. Socio-linguistic refers to language differences such as presence of dialect, stuttering, length of sentences, and the use of descriptive vocabulary. Cognitive refers to knowledge of letters, sounds, an understanding of how reading works, and ability to use phonetic patterns to decode accurately. Furthermore, by finally understanding the terms, I was able to analyze my students’ answers to the interview and analyze my observations about this student from these three perspectives. The inventory made me realize I did not know how to calculate error, accuracy, or self-correction rates prior to working with my student. The inventory gave me specific advice that linked to my learning style, for it told me to review the steps of these calculations in the Harp and Brewer book It also told me to practice making these calculations before starting my actual analysis for I learn best by hands-on experiences and practice. The inventory also reminded me to turn in all my documentation with my reading and writing analysis. I now know that I need hard evidence to prove my students’ progress. As a result, I attached all of my forms, work samples, and notes relating to this assignment. |

8 | CE | AE | The learning style inventory actually did not help me as much this time. I felt like I learned more from actually doing the assessment and then thinking back on it than I did from the inventory. There was some good advice but some of it I feel like I would have figured out on my own. I felt like the inventory activity was interesting but previously I have felt that it offered more help and more suggestions that I used. |

9 | CE | AE | No statement |

10 | AC | AE | No statement |

11 | AC | RO | For both the grasping and processing advice, they helped me review key terms and concepts that would come up and did come up while working on the Student Reading and Writing Analysis. For example, socio-linguistic, socio-cultural and cognitive perspectives. Also, it helped review the procedure at which to complete and turn in. In addition, it talked about the text leveling, which I was unsure how to do until it said to use the Rog & Burton text leveling method. However, the most helpful information was the data analysis and parent letter. These both helped me greatly while looking at the data and finding what I needed to use and writing a sincere, but informational parent letter. |

12 | CE | AE | No statement |

13 | AC | RO | The learning style inventory helped me grasp information on what was involved in the reading and writing analysis assignment by helping me to understand exactly what was expected in the assignment, and by helping me to understand the steps that were needed to be taken in order to complete the assignment. I initially was confused as to the exact steps and what specifically I needed to do to complete the assignment, but after completing the learning style inventory, I received clarified information as to what I needed to do, and where to start in completing the assignment. The specific advice somewhat helped me by explaining from a perspective that I was familiar with, what I needed to do. It also clarified more on a level I was familiar with, and let me know what I needed to do, and corrected me when I had misinterpreted the assignment. I thought the inventory itself helped me more than the specific learning style advice. The learning style inventory helped me process what was involved in the reading and writing analysis because it went into detail as to what was expected in the assignment, and after I filled out the inventory according to how I thought the assignment was to be completed, the inventory helped me to understand the correct order, and exactly what was expected in each category of the assignment. I was able to process the assignment, and the details of what all was put into the project. There were some areas that I did not understand, and the inventory helped me to clarify terms, and what I needed to do to complete those aspects of the assignment. The specific advice partially helped me because it clarified all terminology and elements of the assignment for me, and it described and listed specifically what I needed to do to complete the assignment. I feel more details would have helped me in the specific advice portions, but overall, I felt the inventory helped me out a lot, and it was a worthwhile tool to help me complete the assignment. |

14 | AC | AE | The inventory activity helped me grasp information for the assignment by laying out the steps to complete it. The advice given helped me to re-evaluate the order and the importance of each step of the process. Some advice referred to my grasping style by beginning with, “You like theories.” However, advice such as “Interviews are often overlooked” did not really help me since I know that interviews are important for knowing what the student does and how advanced their communication skills are. I learned that data can be viewed from various perspectives: cognitive with approaching reading task, socio-linguistic perspective analyzing child’s background and knowledge of the reading process, and a socio-cultural perspective involving cultural affects on a child’s reading. I think I learned more with my processing learning style since the advice was more familiar to me and seemed to relate to me more. For example, the advice for the different perspectives began with, “You like to observe before making judgments.” The advice also warned me to be aware of certain behaviors which was not referred to in my grasping style inventory. I relearned the different assessments for reading analysis including Concepts About Print (CAP), Running Records (RR), also Reading Miscue Inventories (RMI). Through this activity, I was reminded of the appropriate grade levels for each of these assessment strategies and how to execute them. I am more comfortable with the reading, writing and spelling processes now from the advice given to me. |

15 | AC | RO | No statement |

16 | CE | AE | I felt the learning style grasping inventory activity was difficult. On each of the sections I never felt confident in what I was supposed to be doing, or what I was suppose to base my decisions on, as far as which item should receive which number. For instance, when the inventory asked me to assign levels of difficulty with 1 being most difficult, I assigned the numbers I felt was going to be most difficult to me and the advice or response told me it should be in a different order. How can the response tell me what should be more or less difficult for me? I liked the additional information it provided, but personally I would rather be given the information and allowed to process it on my own. I don’t feel the process activity helped me with the reading and writing analysis assignment. I was pretty deep into the assignment and already had a good idea of where I wanted to go with the assignment because of the advice the grasping activity gave me. |

17 | AC | AE | No statement |

18 | AC | AE | The learning style inventory activity provided me with knowledge about what I needed to know about the process of doing my reading and writing analysis assignment. Also, the inventory activity had key terminology and definitions that I used to better understand aspects involved in the analysis. The specific advice linked to my learning style did not help me with the assignment and the advice did not seem to change depending on the learning style. The learning style inventory did not help me process information. It just provided a repetition of the information I had previously read. Again I did not see a difference in the specific advice linked to my learning style. |

19 | CE | AE | I thought the difficulty rating feedback didn’t help me too much because it was not always specific and didn’t address my concerns. The step process did help though. It helped me organize what I had to do first and so on. Since I had done most things in the order presented in the grasping feedback I didn’t need too much more advice on this topic. I did however still have questions on how to write or proceed with the analysis. The feedback given for this was somewhat helpful. |