Show and Tell or Something More?

Around the room students sit in groups of four, conversations are focused and animated, interest appears high and laughter is frequent. Photographs, some in color, others black and white, are scattered on desk tops. Within each of the groups one student is sharing a story. One particular photograph amongst the many is held up for group members to see.

The group nearest the front of the room focuses upon a photograph, recently taken, of a typical classroom complete with children, wall displays, and furniture, and near the center of the shot, a student teacher—the storyteller. The story being told is true based upon an experience that occurred during a 5-week-long professional practice (teaching practicum). The digital photo may be contributing to this scene in a variety of ways. It may be acting as a memory stimulant for the storyteller, the image may have symbolic significance representing part of the otherwise unseen context, or the photo may simply illustrate a key aspect of the student teacher’s story.

On the surface this scene might simply be described as a professionally focused show and tell. However, the process that these students are engaged in is intended to have more significant outcomes. What follows is a description of a group-based digital photograph portfolio process aimed at introducing first-year student teachers to the concept of a learning portfolio and to the embedded process of reflection.

What Kind of Portfolio?

Considered in its most literal sense, a portfolio is a receptacle for storing artifacts. However, in the field of education the term portfolio has taken on a number of different and specialized meanings. In the literature, writers often assume their specialized meaning to be shared by the audience, which can result in confusion. Recently the increasing use of computers to store artifacts in digital form for a wide range of purposes, including as electronic assessment management systems, has led to the ambiguous use of the term e-portfolio (Barrett & Knezek, 2003).

A popular educational definition of the term portfolio is a purposeful collection of work that demonstrates effort, progress, and achievement (Paulson, Paulson, & Meyer, 1991). However, this definition does not clarify the actual purpose of the portfolio, which is significant, because the purpose will influence the process undertaken to construct the portfolio as well as the look and feel of the final product (Wolf & Dietz, 1998). In practice portfolio is used to describe collections of work created for a variety of purposes such as learning, assessment, and employment (Penny & Kinslow, 2006). Different definitions exist to distinguish between these. Such definitions often focus more upon the process of portfolio construction rather than a description of the final product.

The portfolio process described in this paper was implemented solely for the purpose of enhancing learning through professional reflection and, therefore, fits a definition articulated by Schulman (2002), who described a documentary history of accomplishments substantiated by work samples, which was only fully realized as a result of reflection, deliberation, and serious conversation.

The decision to develop a portfolio with the single purpose of enhancing learning was a deliberate attempt to ensure that the process was viewed as low stakes and primarily student driven and, therefore, appropriate to promote self-reflection and the ownership of learning effectively (Wolf & Dietz, 1998). Within many teacher education programs over the last decade portfolio processes have been developed, at least in part, to harness these potential benefits (Milman, 2005; Barrett & Wilkerson, 2004). During a similar timeframe, however, teacher education programs have also been influenced by a push for increased levels of assessment authenticity, and as a result of this pressure, the portfolio process also came to be seen as a potential solution to this separate issue (Tillema & Smith, 2007).

In this context it is not surprising that portfolio processes have often been implemented with a combined a range of purposes (Barrett & Knezek, 2003; Fox, Kidd, Painter, & Ritchie 2006). A well-documented issue in the literature concerns the tendency for these differing purposes to conflict with one another, therefore impacting the ability of the process to achieve one or more of its intended outcomes (Breault, 2004; Jones, 2010; Wetzel & Strudler, 2006). It is tempting to consider the possibility of a process of self-reflection occurring free from the contaminating influences of assessment. However, this tension is likely to exist at some level in teaching and learning contexts where the learner must meet stated requirements in order to pass, even if a particular requirement has the promotion of self-reflection as its primary intention. To a limited extent, then, the potential for conflicting purposes applies to this portfolio process as well.

Learning Portfolios – Learning Theory

The learning portfolio process places significant emphasis upon the role self-reflection plays in the generation of new insights. This emphasis on learners generating new learning from a combination of prior knowledge influenced by action-oriented experience locates the learning portfolio clearly within the broad theoretical base of constructivism. The theoretical links between constructivism and the Learning Portfolio process that follow are informed by a helpful overview of constructivism by Martin Dougiamas (1998):

A constructivist perspective views learners as actively engaged in making meaning, and teaching with that approach looks for what students can analyse, investigate, collaborate, share, build and generate based on what they already know, rather than what facts, skills, and processes they can parrot. (Conclusions, para. 5)

At its most general level constructivism acknowledges that learning requires learners to construct knowledge for themselves. A student-centered portfolio process empowering students to select for themselves evidence that most significantly reflects learning from their own perspective clearly mirrors this central constructivist belief (Milman, 2005).

The place of interaction with others, peers in particular, is highly valued in the process of constructing a learning portfolio. An approach that recognizes the importance of social learning will include teaching in contexts that might be personally meaningful to students, negotiating taken-as-shared meanings with students, class discussion, and small-group collaboration. Central to a social constructivist approach is provision of meaningful activity, which is valued above the generation of correct answers. For this reason a learning portfolio process has been developed that emphasizes the importance of collaboration and communication with student teacher peers (Mansvelder-Longayroux, Beijaard, & Verloop, 2007).

The need to explain something for someone else to see has been observed to be a powerful aid to understanding for the person doing the explaining (Stager, 2005). This belief is the basis of constructionism (Papert, 1991). As a social and collaborative activity the construction and subsequent presentation of a learning portfolio requires students to articulate a justification of selected items and the significance to learning that each represents. Reflection is encouraged as a necessary preparation for portfolio presentation. Clarity of thinking is enhanced due to the requirement to document and to explain personal learning in order for others to see and appreciate.

The radical constructivist view of learning emphasizes the existence of simplistic myths created to simplify the act of communication. When students are involved in a process that encourages them to reflect upon and to describe successful or challenging teaching experiences, their many and varied constructs can be revealed. The resulting conversations may enrich the perspectives of all, leading to subsequent reflection upon the range and viability of previously taken-as-shared constructs: “Coming to know is a process of dynamic adaptation towards viable interpretations of experience. The knower does not necessarily construct knowledge of a ‘real’ world” (Dougiamas, 1998, Radical Constructivism, para.3).

The process of creating and sharing a learning portfolio provides a context for constructs to be teased out, challenged, and modified. The variety of initial constructs provides richness to evolving understanding and reveals the complexities hidden within our everyday use of language.

A learning portfolio has been described as an instrument for the construction of the self as a teacher (Antonek, McCormick, & Donato, 1997). The emphasis on self-discovery through reflection and the interpretation of personal experience occurs when students select from experiences and artifacts in order to construct and share their portfolios (Lin, 2008). Further consideration of the importance of storytelling in the process of self-discovery is an area for future investigation.

The Context

The portfolio process discussed in this paper is located within a New Zealand program of primary teacher education. Until recently the majority of New Zealand student teachers have undertaken programs of study within one of several independent colleges of education. In 2007 the last two colleges of education in New Zealand were each merged with their local university. Currently, primary teacher education in New Zealand takes place over 3 years for students entering without a tertiary degree and across durations of between 12 and 15 months for graduate students.

Relative to university courses, colleges of education in New Zealand traditionally implemented intensive and, consequently, expensive programs of teacher education characterized by small group instruction, with consideration given to modelling authentic delivery as much as to course content. Teaching staff were recruited based upon successful professional experience in the relevant school sector in combination with academic qualifications, specialist subject knowledge, and competence. Operationally, the student experience resembled that of a typical secondary school with a full timetable made up of a large number of relatively small yet compulsory courses. Central to the tradition of preservice teacher education in New Zealand has been the integration of a sequence of increasingly challenging professional practice placements occurring at regular intervals throughout the pre-service program. At the time of this study in our university were five placements (23 weeks in total) for the 3-year undergraduate program and three placements (15 weeks in total) for graduate students.

In 1999 the School of Primary Teacher Education, located within what was then a college of education, developed a learning-focused portfolio process for students undertaking the 3-year program of primary teacher education. The process was designed to encourage students to reflect upon the connection between the theory of teaching as contained within college-based course content and the practice of teaching as experienced in each of their school-based professional practice placements.

As a corequisite to each professional practice course in which students enrolled, a corresponding college-based course of professional studies was designed to prepare students to take on increasing levels of classroom challenge. The learning portfolio process was added to the content of each of these professional studies courses. Prior to the inclusion of the portfolio process the professional studies courses were already seen as being full. Nevertheless, the inclusion of the portfolio was required in addition to existing course content.

In brief, the process required student teachers to collect, select and then reflect upon five artifacts that best demonstrated their abilities across six key content areas, comprising each professional studies course. The categories (referred to as aspects) that were required to be evidenced by student-selected artifacts in the portfolio were Observation, Interaction, Designing, Managing, Assessing and Evaluating, Reflection, and the Profession of Teaching. As only five artifacts were to be included, at least one item must be identified as integrating two or more aspects of teacher activity.

As an introduction to the portfolio process, students in their first year of study worked in small groups to create a group portfolio. These students made selections from the artifacts collectively provided by the group. Subsequently, Year 2 and Year 3 students completed a similar process, but individually.

The assessment of each professional studies course was competency based, with a final pass/fail grade awarded. Preexisting assignments used to assess student learning before the introduction of the portfolio were unaffected by the addition of the portfolio. This situation supported the stated intention that the portfolio process promote student learning and reflection. That said, the portfolio task was presented as a course requirement, and within a competency-based course little existed from the perspective of the student to distinguish a course requirement from an assessed task.

Some Issues of the Original Portfolio Process

As the portfolio process became an established component of each professional studies course a number of issues emerged. Before describing the photo portfolio process the initial issues we experienced will be outlined.

One of the much-quoted strengths of portfolios is said to be the potential for the inclusion of authentic evidence. When constructing a portfolio to document a practical activity like teaching, highly authentic artifacts would be those that capture actual classroom events. The act of teaching occurs in real time and space rather than on a piece of paper. This notion has been referred to as “the problem of enactment” (Darling-Hammond & Snyder, 2000) However since being initiated it had been observed that the portfolio process tended to result in paper-based products. Although the six identified aspects of teaching were, without doubt, important components, they tended to present a utilitarian and compartmentalized view of what was intended to be a highly integrated and seamless activity. In practice portfolio artifacts that were the result of actual classroom activity were selected infrequently and, when included, tended to be the documents supporting teaching activity, such as lesson and unit plans and assessment checklists.

Because the six professional studies aspects were already closely related to each of the preexisting college-based assessment tasks, the portfolio process tended to lead students to select artifacts from their course work, which represented teaching in the abstract rather than to identifying evidence from their own classroom teaching. One of the goals of the portfolio was identifying connections between theory and practice, but in most cases neglected to provide the products of classroom practice. Viewed from this perspective the original portfolio process did not appear to be achieving the intended high level of authenticity.

The use of preexisting college-based course work created another significant issue. In most cases the course work included had previously been assessed by members of the college faculty, which compromised both the process and quality of student reflection. Whereas the portfolio process intended to promote self-reflection and the self-awareness that arose from genuine reflection, students’ selection justifications frequently appeared to be based upon the external judgement and feedback comments made by academic staff. Rather than identifying aspects of personal significance, students used the feedback of others to justify their selections.

Time pressures already existed in professional studies courses prior to the inclusion of portfolios. For this reason adding a task that appeared to encourage students to reuse previously completed course work was looked upon by some students and staff as largely pointless.

In response to feedback relating to these issues several staff development sessions were held in order to attempt to broaden the range of evidence that teaching staff might encourage as they facilitated students through the portfolio process. Despite instruction specifically encouraging a wider range of evidence many students continued to use course work and associated external feedback in their portfolios, because the process still contained the original influences that tended to shape responses in that direction.

As has been mentioned, the portfolio process, while not formally assessed, was nevertheless a course requirement, and the possibility of failing the course due to some aspect of the portfolio requirement remained. Possibly, this situation, along with its placement typically in the last week of the course, contributed to the generation of anxiety and a resulting narrow focus on the specific requirements of the task at the expense of the reflective mindset that had been intended. Sessions taken with students to facilitate this portfolio process seemed to occur in an atmosphere of compliance rather than engagement.

The authors, as a professional studies course facilitator and a lecturer, set about a redesign of the portfolio task. The goal was to stay true to the overall intention of encouraging reflection upon the theory/practice link while enhancing the validity of the evidence used and generating greater level of enthusiasm toward the portfolio process itself.

The Photo Portfolio Process

The next section of this paper describes the revised group portfolio process, its implementation with students completing their first professional practice practicum, and the new issues that arose.

Teaching is a practical activity. It follows that professional reflection ought to focus upon something that actually took place in the classroom and from there make connections linking back to course theory. The challenge was how best to capture evidence of something actually taking place. With the rapid progress of digital technology several possibilities exist. The most powerful of these would involve video recording a lesson or part of a lesson, which would capture both the classroom interactions and the dynamic context. However, at this stage digital video recording, editing, and replay would provide logistical challenges that were likely to threaten the overall viability of the new process.

According to Young and Figgins (2002), the power of the pedagogy must drive the technology being implemented. If this fails to occur the technology will not be tied to an authentic context and purpose and will likely become a burden for users. In fact, the complexities of creating digital portfolio artifacts and the resulting threat to the process and intended purpose have been well documented ( Wetzel & Strudler, 2006; Woodward & Nanlohy, 2004). Instead, it was decided that the revised portfolio would be based upon a process involving a set of still photographs taken over the course of the practicum. Although still pictures could not capture interactions or the dynamics of the classroom, they would be a powerful memory aid and, together with telling the accompanying story, a sense of the context would be communicated.

One advantage of this approach was that it required each student to take an active role in interpreting and telling their stories. Talking about practicum experiences would be a natural, easy, and motivating experience for students as presenters, as well as interesting for the other group members as an audience.

At the heart of the portfolio process is reflection. Reflection occurs when there is the need to select portfolio evidence from a larger set of potentially viable options. Additionally the justification of the choices made sheds light on the philosophy and values of the person making the selection. As a result students were required to obtain at least 25 photographs to document their practicum experience. In order to structure the documentation of the practicum, five categories of professional practice were selected, meaning that students would be selecting five photographs for each category.

The five new categories evolved from a set of Satisfactory Teacher Dimensions, which were standards developed by the New Zealand Teachers Council for the reaccreditation of practicing teachers. The Satisfactory Teacher Dimensions had previously been adapted within the College so that they could be appropriately used with student teachers. The five key categories of professional practice were (a) Personal Professional Qualities, (b) Relationships and Communication, (c) Teaching Skills, (d) Professional Knowledge, and (e) Managing the Learning Environment. These five categories were used to structure the formative and summative feedback provided by the associate teacher to the student in the placement record book for each practicum undertaken. Thus, the headings already had significance and were meaningful to students.

The new categories were appropriate because they could be more closely aligned to the enactment of teaching rather than to existing professional studies course work. Another advantage of using the headings contained in the placement record book was that each had been further elaborated by the inclusion of a series of specific descriptors (see Appendix A). When explaining the photo portfolio process to students it was useful to be able to refer to these existing descriptors to help to describe the kinds of teacher actions that might illustrate each category.

On return to college following their first practicum, first-year student teachers began the group portfolio process (see Appendix B).

First, students’ own sets of 25 photographs were individually reduced, following the documented selection process, to five photos (one for each of the categories). Students were guided by the following instructions:

Theory and Practice

You are about to sort and select

Reflect upon your photographs and the “story” each represents.

You are looking for photos which do two things at once,

1. illustrate a connection made between something you learned here at college (theory) and something you did in the classroom (practice).

2. tell a story which “showcases” yourself as a teacher. (See Appendix C.)

Following this individual step, students combined into groups of four and took turns telling the stories that accompanied each of their five selected photographs. These photos were combined with the photos of three other group members, and the resulting set of 20 photos (and stories) was again reduced via group selection to a final portfolio of five photos to be represented by the group.

One important requirement accompanying this stage was that each group member had a photograph included in the final group portfolio. Students were guided by the following instructions.

Group Selection

Now in groups of four, share your selected photos and tell the story of each. As a group, which photographs and stories will you select to illustrate the theory – practice links and to showcase yourselves as teachers? (You need one for each of the five categories) The group “album” needs to contain at least one photo and story from each group member!

Group Justification

Record the justification for each of your groups’ selection decisions on the group photo album recording sheets provided. (See Appendix D.)

Finally students reflected upon the whole process and what each student individually had learned. These reflective statements were collected, and digital photos were taken of each group portfolio before students retrieved their photographs from the group portfolio at the end of the session.

Students were guided by the following instruction:

Reflection

Write a paragraph describing what each of you as individuals in the group have learnt as you completed this process. Finished!!!!! (See Appendix E.)

The photographs that follow illustrate the group portfolio process and provide examples of two group portfolio products.

Implementation Issues of the Photo Portfolio Process

The implementation of a new initiative usually addresses existing problems while at the same time creating new ones. The introduction of the photo portfolio was no exception. The following are issues and considerations that arose on piloting the new process.

The cost of printing photographs can be significant, especially to students on a tight budget. This issue was foreseen and the initial portfolio briefing emphasized that expensive photograph processing was not necessary. As a memory and storytelling aid a clear black and white photo was just as valuable to the process as a glossy color print. The question is then raised about the role the photograph plays in the reflective process.

Although the photograph itself is a strong visual stimulus that adds focus to storytelling, it remains largely symbolic in terms of reflection. In practice the story told about the picture contains the key information about the significance of the experience. As a result, the photograph represents an event but cannot convey the meaning taken from the event. A number of students printed several black and white photographs per A4 page using a standard laser printer, and the financial cost was negligible (see Figure 1). The quality of the reflections does not appear to be influenced by the way in which the photographs are printed.

Figure 1. This portfolio illustrates successful use of laser printed black and white photographs to stimulate reflection.

Having suggested that the quality of the photographs is not critically important to reflection, the process of creating a tangible group-based product required (at this stage at least) that the photos were on paper in hard copy form. Despite clear instructions about the need for photos in hard copy form initially several students arrived with their photos unavailable for viewing except on the screen of their laptop or stored on their flash drive. Clearly, these students were not able to complete the group-based process, which required the sorting and sifting of easily shared images. As a result they were required to return at a later time to complete the process as a group with printed photos. The further development of the portfolio process planned to extend students toward creating individual e-portfolios, known as MyPortfolio, will enable the process of portfolio development to occur without the need for printed photographs.

On their return from practicum many students commented on how difficult it was to capture significant classroom events in a photo. Students shared a number of insights that help to identify the challenges. In a busy classroom it can be difficult to obtain a photograph of a significant moment. Often the context will require that the student teacher be in the picture, which creates the need for someone else to take the photograph (see Figure 2). Associate teachers are also very busy and obviously juggle many other considerations. Ideally photographing will be inconspicuous and not introduce artificiality into the experience; however, this is more easily said than done.

Figure 2. This photo portfolio shows student teachers in action – interacting with children and then making connections between their classroom experiences and learning theory.

Another challenge involves the nature of the reflective process itself. Because reflection by definition occurs after an experience has occurred, students have commented that potentially significant events arose frequently but often only with hindsight could they be identified. Either many many photographs must be taken throughout the practicum to ensure that significant moments have been captured or, some events are restaged at a later time to represent a subsequently identified significant moment. Given the symbolic role played by photographs in the photo portfolio this option may not completely invalidate the process although a degree of authenticity would be compromised.

An unfortunate yet significant barrier to the portfolio process arose for students in some schools where policies were developed to limit the digital recording of identifiable images of children. Given the possibility of uncontrolled distribution and sharing of digital images these policies are quite understandable. The potential threat to security as well as to privacy ensures that schools have a responsibility to respond to such issues. To date those students who have been prevented from photographing identifiable children have been required to think creatively about the composition of their photographs. Once again their reduced choices will affect the authenticity of the photograph if not necessarily of the reflective story it symbolizes.

As can be seen from Figure 3, the photo portfolio process has proved to be an excellent way to enable student teachers to share their professional practice experiences in a positive and interesting way. In spite of this, students have found identifying and describing the links between theory and their practice to be difficult. Although encouraged to link their practice to informally and personally stated theory, students identified this component as most challenging (Jones, 2010). The process described here has been implemented with students who were completing their first professional practicum and who were in their first semester of teacher education. We anticipated that the development of the portfolio process over time and throughout their program of study will reveal the developing ability of students to identify and confidently articulate meaningful theory/practice links.

Figure 3. Student teachers are fully engaged during the portfolio process especially when sharing their teaching stories.

Intended Future Directions in this Portfolio Process

The photo portfolio process introduces students to a learning portfolio through a mixture of individual and group reflection (see Figure 4). Portfolio development and the professional reflection involved needs to continue to evolve for students so that the process becomes one that can be completed independently. The next step in the portfolio journey will occur after students have experienced their second practicum. This step will involve students independently developing an electronic portfolio, MyPortfolio, which they will then present to a group of their peers. The transition to an independent electronic portfolio does not signal a change of purpose from learning to an evaluation portfolio. Much that has been written about the implementation of e-portfolios focuses on the issues associated with standardization, compliance, and the manageability of a process undertaken at least, in part, to contribute to the quality control of graduate teachers (Barrett & Knezek, 2003; Wetzel & Strudler 2006, 2008).

Figure 4. Students each share their five individually selected photographs and explain their reason for the selection. The group then selects again down to the five that will represent the group.

Figure 4. Students each share their five individually selected photographs and explain their reason for the selection. The group then selects again down to the five that will represent the group.

This next step contains two main areas of progression. First, the reflection process embedded within portfolio creation will become an independent task. As a result, the time spent in class on portfolios will focus upon sharing the outcomes of reflection through portfolio presentations. This step reflects a desire to establish reflection as an ongoing and independent professional activity as well as to signal the importance of the reflections themselves by allocating class time to sharing them. These presentations should provide students with further opportunities to consider and identify theory/practice links within their e-portfolio stories. Second, in developing an electronic portfolio students will begin the process of constructing portfolios that are suitable for sharing with a range of professional future audiences.

Moving from hard copy photographs to the use of electronic files and computer software contains a well documented risk that the professional reflection focus becomes lost in the potential frustration arising from unstable and complex technology (Lin, 2008; Woodward & Nanlohy, 2004). Despite this risk there are valid reasons to encourage thoughtful use of new technologies to support learning portfolios as long as simplicity is kept in mind (Pelliccione, Dixon, & Giddings, 2005). To this end a simple PowerPoint portfolio template has been developed to mirror the structure and focus of the group portfolio.

The use of digital photographs will continue to be promoted as the most simple and effective way to illustrate a teaching story. However the electronic portfolio platform will allow those who wish to include a wider range of items to do so. As well as the use of document files, sound and video files may also be included in an e-portfolio. Simplicity has been an important strength of this portfolio process; therefore, the addition of such complexity will be under the control of students who will be monitored to ensure that the focus of the portfolio process remains on professional reflection rather than on technological challenge.

One key feature of the portfolio processes described in this article involves the use made of the portfolio artifacts themselves. Most other portfolios documented in the literature portray portfolio artifacts as the evidence of learning rather than as symbols of a significant learning event. Despite the potential power of technology to capture the enactment of teaching, learning occurs as a result of reflection upon the experience itself. Whatever portfolio item is selected to represent an experience, it is the story told to interpret the experience and justify its selection that has the act of reflection at its heart (see Figure 5). In a future investigation into learning portfolios we hope to focus more closely upon the role that storytelling plays in generating and enhancing learning from experience.

Figure 5. Although photographs focus the attention of story tellers and audience it is the story that reveals its significance to teaching.

References

Antonek, J., McCormick, D., & Donato, R. (1997). The student teacher portfolio as autobiography: Developing a professional identity. Modern Language Journal, 81(1), 15-27.

Barrett, H., & Knezek, D. (2003). e-Portfolios: Issues in assessment, accountability and preservice teacher preparation. Retrieved from Helen Barrett’s electronic portfolios website: http://electronicportfolios.org/portfolios/AERA2003.pdf

Barrett, H., & Wilkerson, J. (2004). Conflicting paradigms in electronic portfolio approaches. Retrieved from Helen Barrett’s electronic portfolios website: http://electronicportfolios.org/systems/paradigms.html

Breault, R. A. (2004). Dissonant themes in preservice portfolio development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(8),847-859.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Snyder, J. (2000). Authentic assessment of teaching in context. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 523-545.

Dougiamas, M. (1998). A journey into constructivism. Retrieved from http://dougiamas.com/writing/constructivism.html

Fox, R., Kidd, J., Painter, D., & Ritchie, G. (2006, Fall). The growth of reflective practice: Teachers’ portfolios as windows and mirrors. The Teacher Educators Journal. Retrieved from http://www.ateva.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/posting-fall-2006.pdf

Jones, E. (2010), A professional practice portfolio for quality learning. Higher education quarterly, 64, 292–312.

Lin, Q. (2008). Preservice teachers’ learning experiences of constructing e-portfolios online. Internet and Higher Education, 11, 194-200.

Mansvelder-Longayroux D., Beijaard D., & Verloop N. (2007). The portfolio as a tool for stimulating reflection by student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23,(1), 47–62.

Milman, N. (2005). Web-based digital teaching portfolios: Fostering reflection and technology competence in preservice teacher education students. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13(3), 373-396.

Papert, S. (1991). Situating constructionism. In I. Harel & S. Papert (Eds.), Constructionism. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Paulson, F. L., Paulson, P. R., & Meyer, C. (1991). What makes a portfolio a portfolio? Educational Leadership, 48(5), 60-63.

Pelliccione, L., Dixon, K., & Giddings, G. (2005), A pre-service teacher education initiative to enhance reflection through the development of e-portfolios. In H. Goss (Ed.), Proceedings of the 22nd annual conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education, 527-534. Brisbane, Australia: ascilite.

Penny, C., & Kinslow, J. (2006). Faculty perceptions of electronic portfolios in a teacher education program. Contemorary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 6(4), 418-435.

Schulman, L. (2002). Portfolio for teacher education: a component of reflective teacher education. Paper presented at annual meeting of American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA.

Stager, G. (2005, August). Papertian constuctionism and the design of productive contexts for learning. Plenary session paper presented at EuroLogo X, Warsaw, Poland.

Tillema, H., & Smith, K. (2007). Portfolio assessment, in search of criteria. Teaching & Teacher Education, 23(4), 442-456.

Wetzel, K., & Strudler, N. (2006). Costs and benefits of electronic portfolios in teacher education: Student voices. Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, 22(3), 69-78.

Wolf, K., & Dietz, M. (1998). Teaching portfolios: Purposes and possibilities. Teacher Education Quarterly, 25(1), 9-22.

Woodward, H., & Nanlohy, P. (2004). Digital portfolios in pre-service teacher education. Assessment in Education Principles Policy and Practice, 11(2), 167-178.

Young, C.A., & Figgins, M.A. (2002). The Q-Folio in action: Using a web-based electonic portfolio to reinvent traditional notions of inquiry, research, and portfolios. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 2(2), 144-169.

Author Note

Brad Meek

University of Canterbury

NEW ZEALAND

email: [email protected]

Philippa Buckley

University of Canterbury

NEW ZEALAND

email: [email protected]

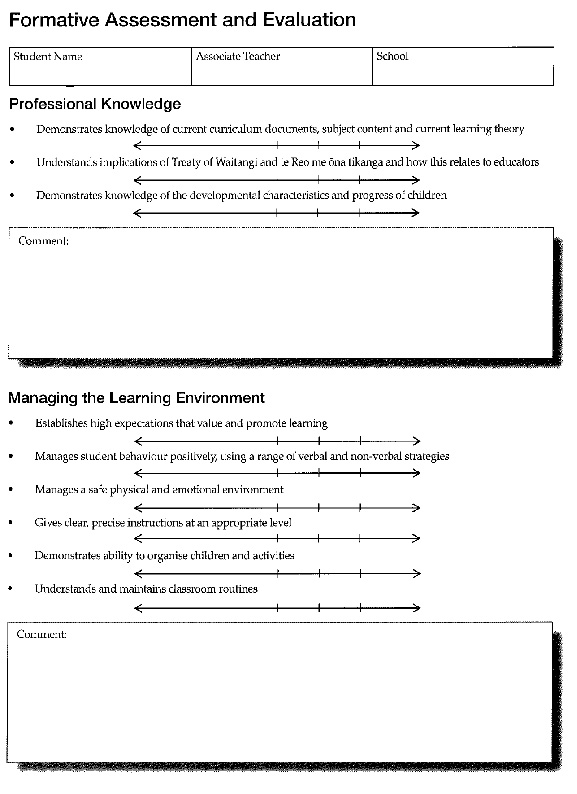

Appendix A

Example Page from the Placement Record Book

Appendix B

The Group Portfolio Process: Written Briefing Instructions

The Group Portfolio Process

Showcase yourself as a teacher:

“A picture tells a thousand words”

Step 1 Individually

Whilst you are on Professional Practice take 25 photographs which document your contribution and experience as fully as you can.

5 photos will represent evidence of your Personal Professional Qualities

5 photos will represent evidence of your Relationships and Communication

5 photos will represent evidence of your Teaching Skills

5 photos will represent evidence of your Professional Knowledge

5 photos will represent evidence of your ability to Manage the Learning Environment

Step 2 Individually

Theory and Practice

You are about to sort and select again!

Reflect upon the photographs and the “story” each represents.

You are looking for photos which do two things at once,

- photos which illustrate a connection made between something you learned here at college (theory) and something you did in the classroom (practice).

- photos with a story which “showcases” yourself as a teacher

You will assemble just 5 photographs (one from each of the five categories above!)

Each photograph will represent a significant teaching/learning story about you. Think about that story first then make some notes to assist in the telling. The story should explain why you selected this particular photo to illustrate a theory – practice link and to showcase yourself as a teacher. Your story should also include a key learning insight that you gained from the experience.

Step 3 Group Selection

Now in groups of four, share your selected photos and tell the story of each. As a group, which photographs and stories will you select to illustrate theory – practice links and to showcase yourselves as teachers? (One for each of the five categories) The group “album” needs to contain at least one photo and story from each group member!

Step 4 Group Justification

Record the justification for each of your groups’ selection decisions on the group photo album recording sheets provided.

Step 5 Reflection

Each of you as an individual is finally to write a reflection describing what you have learnt as you completed this process

Finished!!!!!

Appendix C

Story Preparation/Reflection Sheet

| The story about Photograph 1 Personal Professional Qualities Name____________________ Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

| The story about Photograph 2 Relationships and Communication Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

| The story about Photograph 3 Teaching Skills Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

| The story about Photograph 4 Professional Knowledge Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

| The story about Photograph 5 Manage the Learning Environmen Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

Appendix D –

The Photo Album Template (Printed on A3 paper)

PI501 – Group Portfolio – “WE THE TEACHERS”

Names _____________ ____________ ____________ _____________

| The story about Photograph 1 Personal Professional Qualities Name____________________ Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

| The story about Photograph 2 Relationships and Communication Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

| The story about Photograph 3 Teaching Skills Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

| The story about Photograph 4 Professional Knowledge Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

| The story about Photograph 5 Manage the Learning Environmen Record your key ideas to assist in telling the story

|

Appendix E

Individual Reflection on the Group Portfolio Process

PI 501 Photo Portfolio Final Reflection

Name________________

Write a paragraph describing what you as an individual have learnt as you completed this process.

Name________________

Write a paragraph describing what you as an individual have learnt as you completed this process.

Name________________

Write a paragraph describing what you as an individual have learnt as you completed this process.

Name________________

Write a paragraph describing what you as an individual have learnt as you completed this process.

![]()