Storytelling is a time-honored global custom that allows people to share personal and cultural accounts and perspectives in ways that are unique and individual yet have the potential of being transsituational and transcultural (e.g., see the YouTube video “I Saw A Hole In the Man” ~ A Mayan Story of Why Humanity Suffers). [Editor’s Note: URLs for videos can be found in Resources section at the end of this paper.]

As evidenced by the hieroglyphics of Egypt (PBS, 2007), Greek mythology (Tufts University, n.d.), the West African tribal historians known as griots (Lott, 2002), Aborigine rock art stories (see Rock Art), and Native American elders and wisdom keepers (PBS, n.d.), storytelling has always been used in societies to enculturate its newest members and preserve its history. Storytelling remains an accepted tradition inherent in the social and informal education practices of every culture, and the benefits of the personal narrative in formal academic settings are now being explored and asserted. As preservice and practicing teachers and their students participate in content-related storytelling that is coupled with digital-age technologies (see YouTube video Did You Know), the pedagogical, cultural, and professional development advantages are amplified.

Identity, Efficacy, Inclusion, and Change Through Storytelling

In the best learning conditions, the needs of the students are at the center of the instructional environment, and every attempt is made to engage students actively and to promote inclusivity (Brooks & Brooks, 2000; Hull & Nelson, 2005; McCombs & Whisler, 1997). Showing a digital media production in the classroom that uses voice, music, sounds, pictures, video, and narrative may initially capture students’ attention and pique their interest, but incorporating authentic storytelling into the curriculum yields benefits beyond entertainment. Student- and teacher-created digital stories expand and diversify content within the formal curricula (Egan 1988; Coulter, Michael & Poynor, 2007; Pfahl & Wiessner, 2009) and promote student involvement (Harris, 2007; Sadik, 2008). Content-related narrative development is a pedagogical tool that offers a departure from the traditional methods of teaching and learning in the classroom and enables students to construe meaning individually (see Traditional Teaching on YouTube; Klerfelt, 2004; Wiessner, 2005) and make deeper connections with subject matter content.

Traditional Teaching, and excerpt from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off on YouTube.com

Universal design for learning (UDL; CAST, 2009), an educational framework in which teachers provide students with multiple methods for learning new content and demonstrating learning outcomes, recognizes digital storytelling as an authentic, digital-age pedagogical approach for diverse learners (Rose, Meyer, & Hitchcock, 2005). A narrative strategy may be especially helpful for students who experience difficulty with memorizing facts, since storytelling allows students to access their analytical and creative capabilities (Bruner, 1986; Pfahl & Wiessner, 2009; Speaker, Taylor, & Kamen, 2004) and demonstrate understanding or reveal gaps in their knowledge (Olwell, 1999).

Personal narratives also support learning through increased literacy skills (Allison & Watson, 1994; Bishop & Kimball, 2006; Neuman, 2006; Speaker, 2000); enhanced problem solving skills (Jonassen & Hernandez-Serrano, 2002); and improved listening, recall, and sequencing skills (Reed, 1987).

Many theorists suggest that personal narrative storytelling can help students clarify and articulate identity (Bruner, 1986; Freeman, 1993; Greene, 1995; hooks, 1994; Taylor, 1991). Success is promoted when students are allowed to acknowledge their own identities and are invited to demonstrate those identities in the classroom. Acknowledgement and acceptance of the whole student in the classroom—including the students’ home cultures—build the students’ confidence in their ability to perform academically (Bandura, 1997; Zimmerman, 1998).

By integrating personal narratives as well as textbook content into the curriculum, teachers promote academic- and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Burk, 2000), empowerment (Harris, 2007), and community (hooks, 1994) in their classroom and increase chances of success. What then emerges are stories of self-acceptance, such as the digital story entitled Brown (Video 1), in which a student revealed how she learned to embrace her heritage as a first generation Chicana. Similarly, in My Heroes Don’t Look Like Me (Video 2), a student reflected on a youth absent of superheroes that were noticeably from his culture.

Teacher-facilitated personal narrative creation captures life experiences and provides students with material from which identity and meaning are crafted and connections are made (Wiessner, 2005). By sharing these stories in a classroom setting, “we tell ourselves [and others] who we are, why we are here, how we come to be what we are, what we value most, and how we see the world” (Colombo, Lisle, & Mano, 1997, p. 5). Such is evident in Paul Bunner (Video 3), a story by a teacher that chronicles the travels and adventures of his pioneering grandfather. The teacher situated himself in the story by connecting his grandfather’s journeys with the family that has since resulted and expanded.

The OPUS Collective (http://opuscollective.org) is a collection of culture- and identity-inclusive digital stories created by students in the Teacher Education, Graduate Education, and Ethnic and Women’s Studies programs at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. The ongoing project is designed to share examples of stories that were created in or for the classroom, but have cultural and social value beyond the classroom walls. Students enrolled in my course, Culture Inclusion and Curriculum Enhancement through Digital Storytelling, who elected to showcase their stories are featured. The OPUS Collective, earned its name from the accepted definition of an opus as an original, creative work and from acronym “OPUS” as it reflects the overall purpose of the project, which is to offer perspective using storytelling.

Understanding Cultural Similarities and Uniqueness

Figure 1. Image from the video Wisdom (Video 4).

Figure 1. Image from the video Wisdom (Video 4).

In addition to the catharsis, clarity, and personal connection that can result from storytelling, rich potential exists for discovery of cultural similarities and uniqueness. When story listeners make associations between their own experiences or cultures and those of the storyteller, enlightenment occurs. As stated by Harris (2007), “Stories remind people of how they fit into their culture and connect to others’ culture. One person’s story becomes another person’s story with subtle differences” (p. 111).

Such is demonstrated in Wisdom (Video 4), a teacher-created story that shared perspective on the intracultural and historical topic of light-skinned versus dark-skinned blacks, a social issue that is also observed within Latino and Asian communities (Figure 1; Golash-Boza & Darity, 2008; Perry, Vance, & Helms, 2009). In My Heart or My Lap (Video 5), a teacher conveyed a mother’s pride and heartache as her children matured and moved away from home. The story reflects societal norms and is relatable across cultures.

With storytelling, the role of the story listener is equally as important as that of the teller. During the story circle, the dedicated time for sharing stories under norms that are created by members of the learning community through consensus, the participants are charged to exchange personal narratives without judgment or interruption.

The ability for a story to resonate among the community members is matched by the potential for narratives to illuminate differences (Wiessner, 2005). The symbiotic relationship of storytelling and active listening allows members of a learning community to generate awareness, perspective, and empathy (McAdam, 1993; Noddings, 1991; Pfahl & Wiessner, 2009) and deconstruct assumptions (Caruthers, 2005; Coulter et al., 2007). (A useful handout on active listening from the Educational Broadcasting System may be found at http://www.pbs.org/wnet/wideangle/classroom/handoutA.pdf.) In Happiness (Video 6), a practicing teacher uncovered a connection with a community of people that she initially regarded as less fortunate, a connection that helped her gained newfound perspective for her own life.

Storytelling also provides the impetus for social change by allowing the teller to offer firsthand accounts that raise consciousness of circumstances, events, or conflicts (Coulter et al., 2007; Fernandez, 2002) and enables listeners to replace uninformed assumptions with enlightened viewpoints (Caruthers, 2005; Larson, 1997). Rather than avoiding topics of class, gender, culture, and ethnicity within the classroom, sharing personal narratives promotes awareness of divergent perspectives and belief systems. As a result, opportunities for broader understanding and acceptance within the learning community occur. It is the acknowledgment of differences among students that “leads to discovery of deeper levels of acceptance and connection” (Wiessner, 2005, p. 104).

In My Los Angeles (Video 7), a student addressed the downturn of her community as a result of urban renewal and provided a visual of the forgotten neighborhoods and the lifelong community residents that were displaced by gentrification (defined in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009) Sharing of such humanizing stories creates community among students and teachers of a classroom (Greene, 1995; Lambert, 2008; Reason & Hawkins, 1988).

Pedagogical and Professional Development for Teachers through Storytelling

Use of storytelling as a teacher preparation tool can be traced to the early 1900s when a teacher’s college in New York used storytelling to help the student-teachers make lasting associations between their students’ home lives and the classroom (Grinberg, 2002). Digital storytelling can enhance the classroom in similar ways. By meaningfully integrating storytelling into the curriculum and infusing the storytelling with digital media, teachers can augment their own pedagogical and professional development. However, in order for teachers to include digital storytelling effectively in their curricula, they must first discern value in using storytelling as a pedagogical tool (Coulter et al., 2007; Rakes & Casey, 2002).

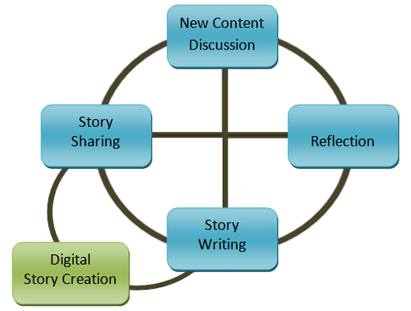

When teachers experience the entire lifecycle for creating the personal narrative themselves (see Figure 2), they are afforded a chance to examine their beliefs and behavior and potentially induce pedagogical and social transformation (Caruthers, 2005; Connelly & Clandinin, 1994). Teachers can use the story writing process as an opportunity to dissect and examine their thoughts about what it means to be a learner and a teacher and then use the analysis to make adjustments in the classroom. When teachers construct new meanings about pedagogy as a result of that process, make changes to their curriculum based on their new understanding, and share those classroom experiences with other teachers, professional development ensues (Milman & Kilbane, 2005).

Figure 2. Content-Related Digital Storytelling (CoRDS) Model

Figure 2. Content-Related Digital Storytelling (CoRDS) Model

An example of pedagogical reflection can be found in the story Bike Riding Lessons (Video 8; Figure 3), in which a teacher recognized her role as a continuous learner as she watched her husband teach their son to ride a bicycle. In the story entitled Younity (Video 9), another teacher recalled a special group of children who helped him make the choice to become a teacher.

Figure 3. Image from the video Bike Riding Lessons (Video 8).

Figure 3. Image from the video Bike Riding Lessons (Video 8).

Through sharing their own stories with their students, teachers allow a genuine exchange to occur in their classroom, and they emerged as persons and not just educators (Klerfelt, 2004; Pfahl & Wiessner, 2009). Such is exemplified in Taking a Stand (Video 10), a story created by a preservice teacher who experienced bullying as an elementary school student. Her intent was to appeal to her students by informing them of the hurt and harm caused by bullying and to urge them to resist peer pressure.

When teachers actively and purposefully include digital storytelling in their curricula, they also address the National Educational Technology Standards for Teachers (International Society for Technology in Education [ISTE], 2008). Teachers facilitate and inspire student learning and creativity by purposefully coupling personal narratives with content to provide authentic learning experiences. They model digital-age work and learning through use of digital media creation technologies to introduce subject matter and storytelling to the class, demonstrate expectations, and develop reusable content. By including digital storytelling in the curriculum while advocating responsible use of digital resources, teachers promote digital citizenship.

Delivery of curriculum-related assignments and activities that require use of digital media technologies enable teachers to design and develop digital-age learning experiences and assessments that assist students in acquiring the creativity, communication, collaboration, information fluency, digital citizenship and technology, skills encompassed by the National Educational Technology Standards for Students (ISTE, 2007). Finally, by creating their own digital stories and sharing their stories and techniques with students and colleagues, teachers engage in professional growth and leadership.

The Content-Related Digital Storytelling (CoRDS) Model

In a learning community, the purpose of content-related storytelling is to have students and teachers make interconnections between subject matter content, themselves, and others. The process of developing content-related digital storytelling consists of five major components, as depicted in Figure 2. New content introduction, reflection, story writing, digital story creation, and story sharing comprise the Content-Related Digital Storytelling (CoRDS) model.

First, the teacher introduces the new subject matter. The introduction consists of any form of content and may include a lesson, activities, or a story that serves as a model or a prompt. Next, students are provided with guides to reflect on a personal experience that directly or tangentially relates to the new content. Students are then instructed to write a personal narrative about their connection to the content. The writing must offer a first person perspective, even when the story topic is someone else. The intent of the narrative is to establish and deepen each student’s individual connection to the content and to include the students’ cultural perspective.

The story writing phase is an iterative negotiation of writing, reading, and revising between the teacher and the students. During this phase, the teacher asks key questions to help the students clarify their thoughts and strengthen their connections to the content. The feedback and communication with the teacher also guide the students in writing unique, succinct, yet fully developed personal narratives. Students then share their stories with the full learning community as the teacher interweaves reinforcing discussions about the new content.

The digital story creation component of the content-related digital storytelling process is ancillary and inextricably tied to the story writing phase of the lifecycle. The digital storytelling process should not usurp the story writing process, but should follow it. When embedded into the lifecycle, digital story creation enhances the written story through images, sounds, and video editing technologies that support the story. Personal artifacts such as old photographs, home movies, a passport, old letters, drawings, a piece of clothing, or a birth certificate, are digitalized and juxtaposed using the editing technologies.

The belongings provide human element and cultural perspective. Accompanying music helps reveal the story through selection of complementary genres and tempos. All elements of the 2-minute to 4-minute production harmonize and work in concert with the most important component of the opus: the storyteller’s own speaking voice, which gives life to the story. An example of a content-related digital story is a story called Raices (Video 11), in which the storyteller reflects on his family’s agricultural roots and their ties to a community garden. Such a story could be used by a teacher to introduce, for instance, ninth grade science content standards for California Public Schools (California Department of Education, 2003, p. 54). Digital stories that result from content-related digital story creation can be subsequently reused in the classroom to reinforce the new content connections made by students within the same learning community and can also be used as examples to introduce new content to future students.

Implications

Digital storytelling is important and relevant inside and beyond the classroom. For students, the self-awareness and self-validation that result from orchestrating an identity-inclusive personal narrative can be adapted to address other aspects of their educational and social experiences. Additionally, the potential for expanded worldviews and global awareness become boundless when students experience the unique yet identifiable stories of others.

From a practical perspective, digital storytelling can provide K-12 students with needed competencies. Content-related digital storytelling offers students practice with pairing writing and new media technologies to demonstrate transfer of learning. Students can also gain valuable experience with appropriate use of and attribution for digital content and copyrighted materials. Such proficiencies are necessary as K-12 students progress academically and transition into college settings.

For teachers, the implications of digital storytelling are also significant. Use of digital storytelling as a pedagogical instrument can enable teachers to distinguish themselves as educators who actively acknowledge and embrace the learning styles preferences and technological realities of their digital-age students. Digital storytelling can also provide teachers with opportunities to help students improve their information and technology literacy skills by introducing them to and reminding them of their responsibilities as consumers of digital content and copyright materials. Moreover, the ethnographic benefits of digital storytelling in the classroom can provide teachers with insight that will allow them to make compassionate connections with the students, families, and communities they serve.

Conclusion

Writing personal narratives provides students with additional techniques for making deeper connections to subject matter. Storytelling helps students clarify and articulate their identities. By meaningfully integrating personal narratives as well as textbook content into the curriculum, teachers promote academic and self-efficacy, empowerment, and community-building opportunities in their classroom and increase chances of student success. Similar to the way blending musical sounds of varying intonation can produce a pleasing melody, acknowledgement of distinct, whole-person identities in the classroom allows the learning community to harmonize in its understanding and acceptance of cultural similarities and differences and to experience social change through awareness, perspective, empathy, and deconstruction of assumptions.

The CoRDS model provides teachers with a pedagogical tool that works concertedly with other subject matter approaches and allows students to access their analytical and creative faculties to demonstrate understanding or reveal gaps in their knowledge. By using the CoRDS model to synthesize content, storytelling, and digital media technologies, teachers also expand their own pedagogical and professional development through reflection, pedagogical and social transformation, and practice and mastery of technology standards.

The origins of storytelling are unknown, but its ability to persist and transcend is undeniable (see YouTube video Mark Logic User Conference 2009 Opening video) . Knowing how to produce content-related digital stories for purposeful inclusion in a curriculum is an important skill for teachers to acquire. When creative works that result from the process are shared, they become authentic reusable, portable, sharable, and adaptable instruments that represent the learning successes of the K-12 students and the pedagogical and professional growth of the teacher.

References

Allison, D. T., & Watson, J. A. (1994). The significance of adult storybook reading styles on the development of young children’s emergent reading. Journal of Reading, 34(1), 57-72.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

Bishop, K., & Kimball, M. (2006). Engaging students in storytelling. Teacher Librarian, 33(4), 3-38.

Brooks, J. G., & Brooks, M. G. (2000). In search of understanding: The case for constructivist classrooms. UpperSaddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burk, N. (2000). Empowering at-risk students: Storytelling as a pedagogical tool. Paper presented at the 86th annual meeting of the National Communication Association, Seattle, WA.

California Department of Education. (2003). Science content standards for California public schools, kindergarten through grade twelve. Retrieved from http://www.cde.ca.gov/be/st/ss/documents/sciencestnd.pdf

Caruthers, L. (2005). The unfinished agenda of school desegregation: Using storytelling to deconstruct the dangerous memories of the American mind. Educational Studies, 37(1), 24-40.

CAST. (2009). Universal design for learning. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Health effects of gentrification. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HEALTHYPLACES/healthtopics/gentrification.htm

Colombo, G., Lisle, B., & Mano, S. (1997). Framework: Culture, storytelling and college writing. Boston, Massachusetts: Bedford Books.

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1994). Telling teaching stories. Teacher Education Quarterly, 21(1), 145-158.

Coulter, C., Michael, C., & Poynor, L. (2007). Storytelling as pedagogy: An unexpected outcome of narrative inquiry. Curriculum Inquiry, 37(2), 103-122. doi:10.1111/j.1467-873X.2007.00375.x

Egan, K. (1988). Teaching as storytelling: An alternative approach to teaching and the curriculum. London, England: Routledge.

Fernandez, L. (2002). Telling stories about school: Using critical race and Latino critical theories to document Latina/ Latino education and resistance. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 45-65.

Freeman, M. (1993). Rewriting the self. NewYork, NY: Routledge

Golash-Boza, T., & Darity, W. A. (2008). Latino racial choices. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(5), 899-934. doi:10.1080/01419870701568858

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Grinberg, J. G. A. (2002). “I had never been exposed to teaching like that”: Progressive teacher education at Bank Street during the 1930’s. Teachers College Record, 104(7), 1422–1460.

Harris, R. (2007). Blending narratives: A storytelling strategy for social studies. The Social Studies, 98(3), 111-115.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress. New York, NY: Routledge

Hull, G., & Nelson, M. (2005). Locating the semiotic power of multimodality. Written Communication, 22(2), 224-261. doi:10.1177/0741088304274170

International Society for Technology in Education. (2007). The ISTE national educational technology standards and performance indicators for students. Retrieved from http://www.iste.org/Content/NavigationMenu/NETS/ForStudents/NETS_for_Students.htm

International Society for Technology in Education. (2008). The ISTE national educational technology standards and performance indicators for teachers. Retrieved from http://www.iste.org/Content/NavigationMenu/NETS/ForTeachers/NETS_for_Teachers.htm

Jonassen, D.H., & Hernandez-Serrano, J. (2002). Case-based reasoning and instructional design using stories to support problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(2), 65-77.

Klerfelt, A. (2004). Ban the computer or make it a storytelling machine—Bridging the gap between the children’s media culture and preschool. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 48(1), 73-93. doi:10.1080/0031383032000149850

Lambert, J. (2008). Digital storytelling (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Digital Diner Press.

Larson, C. L. (1997). Re-presenting the subject: Problems in personal narrative inquiry. Qualitative Studies in Education, 10(4), 455–470.

Lott J. (2002). Keepers of history. Retrieved from the Penn State Online Research website: http://www.rps.psu.edu/0205/keepers.html

McAdams, D. P (1993). The stories we live by. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

McCombs, B., & Whisler, J. S.(1997). The learner-centered classroom and school: strategies for increasing student motivation and achievement. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass.

Milman, N. B., & Kilbane, C. R. (2005). Digital teaching portfolios: Catalysts for fostering authentic professional development. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 31(3), 51-65.

Neuman, S. (2006). Speak up! Scholastic Early Childhood Today, 20(4), 12-13.

Noddings, N. (1991). Stories lives tell. New York, NY: Teachers College Press

Olwell, R. (1999). Use narrative to teach middle school students about Reconstruction. The Social Studies, 90(5), 205-208.

Pfahl, N. L., & Wiessner, C. A. (2009). Creating new directions with story: Narrating life experience as story in community adult education contexts. Adult Learning, 18(3), 9-13.

Perry, J. C., Vance, K. S., & Helms, J. E. (2009). Using the People of Color Racial Identity Attitude Scale among Asian American college students: An exploratory factor analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 2, 252-260. doi:10.1037/a0016147

PBS. (1997). Nova online adventure: Pyramids. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/pyramid/hieroglyph/hieroglyph2.html

PBS. (n.d.). Circle of stories: Many voices. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/circleofstories/voices/index.html

Rakes, G., & Casey, H. (2002). An analysis of teacher concerns toward instructional technology. International Journal of Educational Technology, 3(1). Retrieved from http://www.ed.uiuc.edu/ijet/v3n1/rakes/index.html

Reason, P., & Hawkins, P. (1988). Storytelling as inquiry. In P. Reason (Ed.), Inquiry in action (pp. 79-101). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Reed, B. (1987). Storytelling: What it can teach. School Library Journal, 34(2), 35-39.

Rose, D., Meyer, A., & Hitchcock, C. (Eds.). (2005). The universally designed classroom: Accessible curriculum and digital technologies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Sadik, A. (2008). Digital storytelling: A meaningful technology-integrated approach for engaged student learning. Educational Technology Research & Development, 56(4), 487-506. doi:10.1007/s11423-008-9091-8

Speaker, K. (2000). The art of storytelling: A collegiate connection to professional development schools. Education 121(1), 184-87.

Speaker, K., Taylor, D., & Kamen, R. (2004). Storytelling: Enhancing language acquisition in young children. Education, 125(1), 3-13.

Taylor, C. (1991). The ethics of authenticity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tufts University. (n.d.) Perseus project. Retrieved from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/Herakles/stories.html

Wiessner, C. (2005). Storytellers: Women crafting new knowing and better worlds. Convergence, 38, 101-119

Zimmerman, B. J. (1998). The development of academic self-efficacy. Educational Psychologist, 33(2/3), 73.

Author Note

Teshia Young Roby

California State Polytechnic University Pomona

Email: [email protected]

Digital Storytelling Examples From the Opus Collective

Bike Riding Lessons – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/bikeriding/index.html

Brown – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/brown/index.html

Happiness – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/happiness/index.html

My Heart or My Lap – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/heartorlap/index.html

My Heroes Don’t Look Like Me – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/myhero/index.html

My Los Angeles – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/mylosangeles/index.html

Paul Bunner – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/paulbrunner/index.html

Raices – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/raices/index.html

Taking a Stand – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/takingastand/index.html

Wisdom – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/wisdom/index.html

Younity – http://www.opuscollective.org/examples/younity/index.html

YouTube Videos

Did You Know? – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cL9Wu2kWwSY

information by Karl Fisch, Scott McLeod, and Jeff Brenman, adapted by Sony BMG

“I Saw a Hole in the Man,” a Mayan Story of Why Humanity Suffers– http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1hnHwFiUwA

Example of the art of storytelling, excerpt from “Apocalypto”

Mark Logic User Conference 2009 Opening video – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BxncR6-SHjI

The official name of this piece is “Information Is Now Free.”

Rock Art – http://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/player/places/regions-places/australia-and-oceania/australia_rockart.html

National Geographic

Traditional Teaching– http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EQKcxnFUMxk

Excerpt from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

![]()