The body keeps track of trauma. When I started a tenure track position and learned that I would be responsible for teaching the course English Language: Grammar and Usage in the English Education Department, my body began to ache in the way it did when I was 17. In the way it did during my first few weeks in a required course called African Diaspora in the World at Spelman College. My body remembered how it felt when my Spelman sister referred to my voice as “ghetto” (see Video 1). Hearing the title of the course I would be teaching reminded me viscerally of the pivotal moment when I understood my grammar, language, and accent marked me as a cultural outsider. In the Video 1, I explain how I was nearly silent for three years, unwilling to talk in class unless I absolutely had to, out of a fear of being seen as less than others based on my grammar and language.

Video 1 First Experience With Grammar

My body still remembers the energy it took to keep my hand down when one of my professors, Dr. Michelle Hite, asked if anyone had any questions. Dr. Hite was later key in my process of finding my voice, as she validated my presence at Spelman College. She identified the beauty in my “mother tongue” (Tan,1990) and described the linguistic violence (Baker-Bell, 2020) I experienced.

Unfortunately, Dr. Hite’s affirmation only went so far. When I began full-time student teaching in a high school English Language Arts department, my Black cooperating teacher insisted I had to make sure my “subjects and verbs” agreed when I spoke to students. All the confidence I gained with Dr. Hite slipped away. To have anti-Black linguistic violence enacted upon me by a Black woman tasked with mentoring me was deeply traumatic. I was traumatized into code switching to ensure that my language and grammar matched my mentor’s expectations. Even worse, I turned around and enacted anti-Black linguistic violence in my classroom as an English Language Arts high school teacher.

I demanded my students use white Mainstream English (wME; Baker-Bell, 2020) when speaking or writing for class. I consistently corrected them when they used Black English, when their subjects and verbs did not agree, and when they used their mother tongue (Tan, 1990).

What I did not realize at the time was that I was enacting anti-Black violence and trauma upon my students. Now, as I continue to unpack my own personal experiences as a Black woman and educator through the archeology of self (Sealey-Ruiz, 2018), I am better equipped to articulate the impact of anti-Blackness, internalized anti-Blackness, and anti-Blackness in English education programs. This experience has led me to the work of exploring the impact of centering Blackness in English Education programs. I saw this work as my moral responsibility, given the harm I enacted upon my Black students as a high school English language arts (ELA) teacher. I want to make sure that the pattern of anti-Black violence that began long before I arrived at Spelman College is not carried forward by the students I teach in English Education programs.

To be as purposeful and strategic as possible, I designed a study focused on using technology as a pedagogical tool in a language and grammar course to center Blackness in an English Education teacher preparation program. I used two questions to shape my thinking and research:

- What does centering Blackness in an English Education language and grammar course look like in theory (Black theorists and ways of knowing) and practice (pedagogical tools, specifically, technology)?

- In what ways does centering Blackness in an English Education language and grammar course increase students’ criticality of anti-Blackness in English Education and K-12 classrooms?

Background on Word Choice and Context in This Study

Blackness

When using the word Blackness, I am thinking of Johnson (2019) who defined Blackness as an embodied experience that is connected to Black people’s culture, race, ethnicity, language, literacy, relation, and humanity. Dumas and ross (2016) described Blackness as an act of self and collective care and position it as a source of resistance.

Johnson (2019) said that that Blackness is not monolithic but multifaceted – dynamic and fluid, intertwined with joy, struggle, hope, love, pain, and light. It is a source of genius (Muhammad, 2020). Blackness is symbolic of the fight for liberation from oppression, racism, xenophobia, linguistic violence, economic justice, white supremacy, and patriarchy (Johnson, 2019). During this time of two pandemics (racism and COVID-19), Black people continue to shout “Black Lives Matter” because of white society’s disdain and mistreatment of Blackness and Black humanity.

Criticality

When I consider students’ criticality, I am referencing a step toward social change and transformation that is linked to the ideals of liberation, security, and protection as articulated by Muhammad (2020). Building on her earlier work, Muhammad offered criticality as a way to increase students’ ability to read, write, and think in ways of understanding, power, privilege, social justice, and oppression of populations who have been historically marginalized.

Most importantly, by developing students’ criticality educators can better humanize practices inside and outside of the classroom. My study demonstrates that Black liberation is action orientated, requiring educators to shift beyond merely talking about the changes that must be made to demonstrate that Black Lives Matter.

Framework for Being, Teaching and Learning

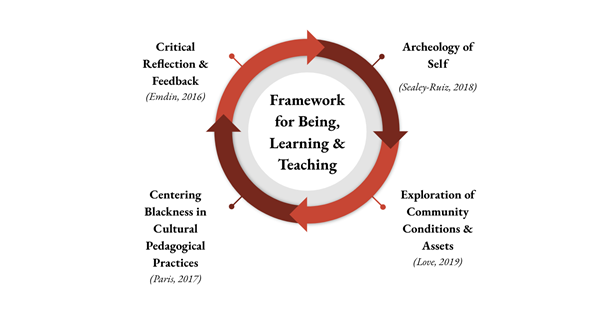

I created the Framework of Being, Learning, and Teaching (FBLT; Figure 1) as an organizing structure for my pedagogy during my first year as a professor of professional practice in 2017. I have used this framework in all of the courses I have taught, including the most recent, English Language: Grammar and Usage,in 2020.

Figure 1 Framework for Being, Learning, and Teaching

My preservice teachers eagerly asked me about best strategies or for tools to fill their toolbox for teaching Black students. Each time a student asked I got the sense they thought Black children needed fixing, and I had the magic wand as a Black professor. The FBLT allowed me to move the focus away from me and Black children to the preservice teachers themselves.

This shift was necessary because, in my experience, they overlooked the necessary step of unpacking themselves before thinking about teaching. Multiple ways of thinking about how to approach the classroom have been identified, including culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings, 1995) and culturally sustaining pedagogy (Paris, 2012). I noticed that many educators revered these pedagogical practices as magic bullets, without clearly understanding their role in implementing them.

At the same time, many educators positioned these practices as a reflection of students’ deficits, rather than seeing the assets that exist in Black and Brown communities (Bertrand & Porcher, 2020). The FBLT framework allows current and future educators to engage in a continuous process; the work begins with self and continues through reflection. It is meant to prompt daily conscious choices about the ways educators show up in the world while exploring the beauty, genius (Muhammad, 2020), and complexities of their students and their communities. It encourages thoughtful implementation of best practices for teaching and learning with and for students by supporting reflection on the impact of the efforts.

FBLT has four elements building on the existing work of Black scholars and my own experiences as a teacher educator: archeology of self (Sealey-Ruiz, 2018), exploration of assets and conditions (Love, 2019) of students and their communities, centering Blackness in culturally sustaining pedagogical practices (Paris, 2012), and critical reflection (Emdin, 2016).

The Archeology of Self

I first learned about Sealey-Ruiz’s (2018) archeology of self during my first year as a professor of professional practice. She defines the archeology of self as a deep excavation and exploration of beliefs, biases, and ideas that shape how people engage in the work (Sealey-Ruiz, 2020). It is rooted in racial literacy, in which those who use the process can engage in necessary reflection about their racial beliefs and practices (Sealey-Ruiz, 2020). More specifically, Sealey-Ruiz (2013) defines racial literacy as “a skill and practice in which individuals are able to probe the existence of racism and examine the effects of race and institutionalized systems on their experiences and representations in US society” (p. 386). Racial literacy requires self-reflection, along with moral, political, and cultural decisions about how teachers can be catalysts for societal changes (Sealey-Ruiz, 2011). Sealey-Ruiz (2020) explored how racial literacy can be sustained through the archeology of self.

While I was already implementing opportunities for students to explore their identities in the courses I taught, the archeology of self concept gave me more precise language and led to my creation of FBLT. The self-work in this framework, also known as “being,” has to be the foundation of learning and teaching. If left unpacked and unexplored, it has the power to negatively impact the lives of students (Sealey-Ruiz, 2018).

The archeological dig is imperative because the preservice teachers cannot understand the communities of others until they know who they are (Howard, 1999). What happens in most English Education programs is a focus on pedagogical strategies, with limited reflection from preservice teachers about how they will be interacting with those strategies. Furthermore, surface level conversations are held about the importance of developing relationships with students that they teach, but no concrete information is discussed about how to do it.

Exploration of Assets and Conditions of Students and Communities

Once students have begun the journey of unpacking self, they are introduced to the importance of exploring the assets and conditions of their future students and communities. This aspect of the framework is referred to as learning. Focusing on the assets of students and communities of color is imperative, because many white cisgender monolingual students have negative perceptions of students and communities of color (Bertrand & Porcher, 2020).

Although we discuss students and communities of color, I specifically focus on Black students and their communities. Wynter-Hoyte and Smith (2020) argued that anti-Blackness violence in schooling impacts white students, because they receive messages of Black inferiority, omission, and inaccurate historical representations and develop negative attitudes about Blackness. Through purposefully curated assignments, students explore the beauty and genius (Muhammad, 2020) of students and communities of color. Students also explore the conditions that are systematic in society and schools that contribute to the conditions of communities of color. With understanding that students enter classrooms with funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1991), not in need of saving, but cultivating the genius (Muhammad, 2020) of who they are, they are then ready for exploring cultural pedagogical strategies that center Blackness.

Centering Blackness in Cultural Pedagogical Strategies

After students have explored the assets and conditions of people of color and their communities, then students engage in pedagogical practices that center Blackness in culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings, 1995) and culturally sustaining pedagogical practices (Paris, 2012). This element of the framework is known as teaching. With this framework, the students now have a lens of their own experiences and the experiences of people of color to guide their practices of centering Blackness in pedagogical practices. I model culturally relevant and sustaining strategies in my own teaching and have students reflect on ways that they can use these strategies in their future classrooms.

Critical Reflection

The final component of the FBLT is ongoing, critical reflection. This critical reflection requires me and the students to reflect upon what is going well in the course and what can be improved. Students are expected to continue this reflection in their personal lives. During class, I stress the importance of expanding beyond the classroom to personal accountability in not enacting anti-Blackness in their personal lives. This work occurs through course reflections and cogenerative dialogues (Emdin, 2016).

Course Setting

At the beginning of the pandemic, there was a lot of talk of reimagining K-12 and teacher education as a system that centers Blackness, especially since the inception of schooling in America is not built for Black children (Warren & Coles, 2020). As a Black scholar-practitioner, I was hopeful for the future of education and teacher education. However, when I received the course syllabi for the English Language: Grammar and Usage course, it included practices that made me less hopeful and the syllabi enforced anti-Blackness. To shift from talking about it to being about it, I used pedagogical technology tools to unpack, interrogate and reimagine the content of the course.

I surveyed students before the course began, and the students boasted about their wME grammar and language skills. They expressed that they wanted to get even better by focusing on learning rules of wME and grammar to increase their professional writing and speaking skills. They also wanted to learn best strategies for correcting and teaching their future students.

Based on their responses, it was evident that students were not aware of diverse grammars, nor were they aware of the assets of diverse grammars, as evidenced by their desire to learn to correct students. Furthermore, it was evident that until students unpacked and understood their own identity, they would have difficulty seeing and interrogating the violence of enforcing wME (Baker-Bell, 2020) in K-12 and English Education programs.

Nonetheless, I knew the work had to begin. Black children’s freedom in schools could not wait. In the redesigned course, students would be expected to unpack and interrogate their experiences with grammar and language, explore the assets and conditions of diverse grammars and languages, and reimagine grammar and language instruction in K-12 ELA classrooms and English Education programs.

Participants

All participant data were collected from the preservice teachers enrolled in a required course in the English Education and Elementary Teacher Education licensure program. Data were collected during the fall 2020 semester. All preservice teachers enrolled in the course were required to complete the assignments described in the data collection. When they completed the assignments, they were given multiple opportunities to engage in metacognition about their responses, offer reflections on the assignments, and make adjustments to demonstrate their new learning. Participation in this study was completely voluntary and not evaluative. The class included 31 students, and 21 students were teacher education students. Twenty-nine of the students identified as white and two identified as Asian.

Methodology

This study used Self-Study in Teacher Education Practices (S-STEP), a type of practitioner inquiry undertaken by teacher educators with the dual purpose of improving their practice while also acknowledging their role in teaching and learning in the larger project of preparing high-quality teachers to teach with the goal of equity for all students (Sharkey, 2018). Self-study is a methodology for exploring professional practice (Appleget et al., 2020).

I used the five elements of self-study outlined by La Boskey (2004) to shape my study: self-initiated and focused, improvement aimed, interactive, qualitatively collected data sources, and validity based on trustworthiness of results. I selected this approach because it is an inquiry approach well-suited to exploring the challenges of effectively teaching teachers about equity, diversity, and social justice (Kitchen, 2020).

In addition, S-STEP has made a meaningful contribution to the scholarship of teacher education pedagogies and practices (Loughran, 2014; Sharkey, 2018; Zeichner, 2007). The structure allowed me to act as a participant, teacher educator, and researcher (Appleget et al., 2020). By taking on multiple identities, I hoped to grow and reflect on the design, implementation of pedagogical technology tools, and engagement of preservice teachers in the English Language: Grammar and Usage course. In doing the work of self-study, I learned about myself, my strengths, my challenges of enacting linguistic justice in a language and grammar usage course and worked alongside my students to determine solutions to improve English Education and K-12 ELA teaching of grammar and language that does not enact anti-Black linguistic violence (Hernandez-Saca et al., 2020).

Data Collection and Data Sources

I collected a large pool of qualitative data over the course of the semester. Sources included reflective memos about the course, student course assignments, student comments, student engagement, and reflections (see Table 1). I built a routine for ongoing and recursive data analysis throughout the semester, focused on inductively generated codes (Saldaña, 2015; Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Table 1 Data Sources and Number of Data Sources

| Data Sources | Number of Data Sources |

|---|---|

| Reflective Memos: A memo was written after each week of classes. The class met twice a week. | 12 |

| Student Course Assignments: Analyzed course assignments of teacher education students only. | |

| 1. Twitter Chats 2. Analysis Essays 3. PhotoVoice Project 3. Cycle of Socialization 4. Exploring the Assets of Diverse Languages 5. Linguistic Demands | Twitter Chats (189 tweets) Analysis Essays (21) PhotoVoice Projects (21) Cycle of Socialization (21) Exploring Assets of Diverse Languages (5 groups of students) Linguistic Demands (5 groups of students) |

| Student Comments & Engagement: Notes taken from our 12 course meetings. | 24 |

| Reflections: Students provide reflective feedback during each class period. Students also provided two google forms with reflective feedback. | Weekly Feedback: 12 Mid-semester Feedback: 24 End of Year Feedback: 16 |

Data Coding

The assignments listed in Table 2 were included in the data analysis. Data analysis included three rounds of coding. The first round of coding focused on the specific technology elements of the course that allowed me as the instructor to center Blackness. In this round of coding, I searched specifically for technology programs and pedagogical tools that I utilized throughout the course, such as Padlet, Twitter, Jamboard, Podcast, TikTok, Screencast, and Photovoice.

Table 2 Course Assignments and Details

| Elements of Course | Details |

|---|---|

| Twitter Chat | Three times throughout the semester, students are expected to engage in the #TeacherEduMatters chat on the assigned dates. The purpose of the chat is to discuss the course content, learning and reflections with classmates and other educators around the world. |

| Analysis Paper | In five pages, double spaced, respond to the prompt: Reimagine an English Language Arts classroom grammar course, specifically the instruction of grammar and its usage, that does enact linguistic violence and anti-Blackness. Ensure to use at least five of the readings from the course to support your response. |

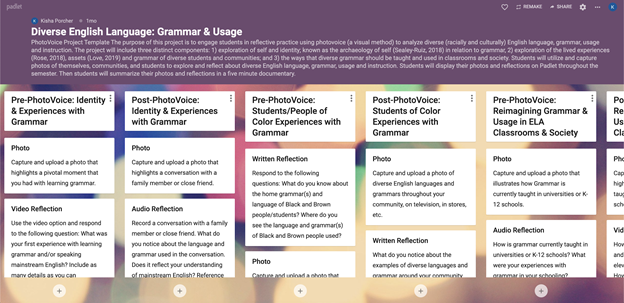

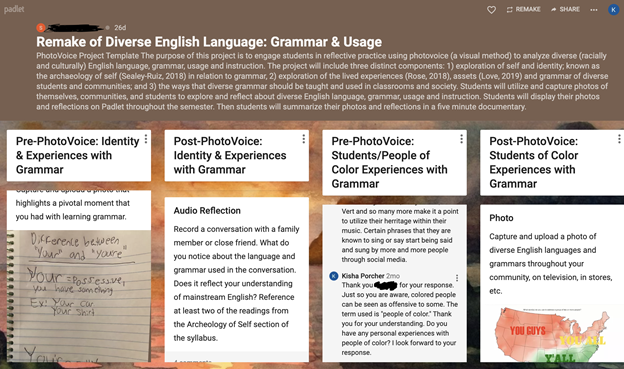

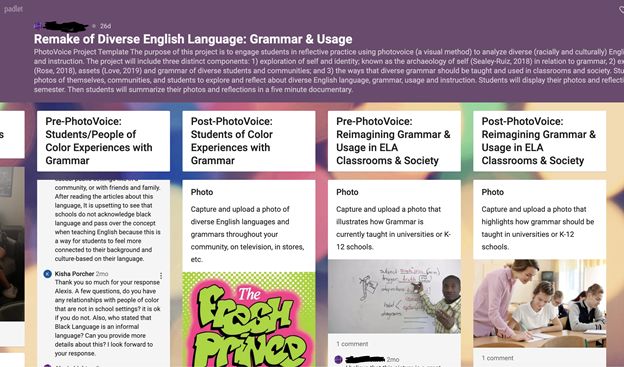

| PhotoVoice Project | The purpose of this project is to engage students in reflective practice using photovoice (a visual method) to analyze diverse (racially and culturally) English language, grammar, usage and instruction. The project will include three distinct components: 1) exploration of self and identity; known as the archaeology of self (Sealey-Ruiz, 2018) in relation to grammar, 2) exploration of the lived experiences (Rose, 2018), assets (Love, 2019) and grammar of diverse students and communities; and 3) the ways that diverse grammar should be taught and used in classrooms and society. Students will utilize and capture photos of themselves, communities, and students to explore and reflect about diverse English language, grammar, usage and instruction. Students will display their photos and reflections on Padlet throughout the semester. Then students will summarize their photos and reflections in a five-minute documentary. |

| Classwork/Homework Assignments | 1. Cycle of Socialization. 2. Exploring the Assets of Diverse Languages. 3. Linguistic Demands. |

The second round of coding aimed to narrow in on students’ responses in the course to the specific elements that centered Blackness in theories and pedagogical practices. The third round focused on students’ criticality in their responses to the specific elements of the course that centered Blackness in theories and pedagogical practices. During this round of coding, I focused specifically on words that students used, such as social change, change, transformation, freedom, and liberation. After the three rounds of coding, the data were grouped based on the research questions.

Findings

My primary goal when teaching the course was to center Blackness, and decenter wME. The purpose of my study was to document the impact of my pedagogical decisions and tools.

Research Question 1: Centering Blackness in Theory and Practice

For the first research question, I focused on capturing the impact of centering Blackness in theory and practice. I found that centering Blackness in theory and practice involved course text selection, use of Black language, and technological strategies.

Centering Blackness in the Course Text Selection

When I was assigned the course to teach, the trauma that I felt due to my own personal experiences with grammar and language in English Education intensified when I read through the syllabus prepared by the other professors in the program. The document made it clear the course had centered learning about and applying wME. Readings and activities included different perspectives on a variety of languages but the syllabus indicated no clear expectation for students to learn about the rules and elements of those languages.

Meanwhile, no consideration was given to diverse languages and students’ future teaching practice. Most importantly, the syllabi indicated that students would learn the history of grammar and language through the eyes of whiteness (European colonizers’ account), also described as “the white gaze” (Morrison, 1994; Wynter-Hote & Smith, 2020).

Readings for the course focused on students learning the rules of wME, and nonwhite authors were added as supplements and on the margins. On the surface, and to the previous professors, it likely seemed inclusive; however, it implied that Black authors’ work cannot stand alone as knowledge unless it is coupled with white authors’ work. Teacher educators must understand that choosing Eurocentric texts that omit the lived realities of Black people or misrepresent the multiple ways of being Black, leads to anti-Blackness and the devaluation of Black life. It is a form of anti-Blackness and racial violence (Johnson, 2018). It is not an issue in only this course, as it is present in most courses that attempt to focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion (Bertrand & Porcher, 2020).

My first move was to center the course around a single text, Dr. April Baker-Bell’s (2020) Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity and Pedagogy. By doing so, I would shift the history of learning grammar and language from the white gaze to the Black gaze (Morrison, 1994; Porcher & Bertrand, 2020). Johnson et al. (2017) argued that using texts from Black radical tradition opposes Eurocentric dominant schooling practices, which are generally organized around the words and thoughts of white people.

Furthermore, Black radical tradition is often at odds with European thought and has to reimagine a collective sense of community to combat European state violence (Johnson et al., 2017). Centering Blackness in the course text selection was only the beginning. I also centered Blackness in my own language.

Professor as the Pedagogy: Centering Blackness in My Language

Baker-Bell (2020) opens her book with the following:

If y’all actually believe that using “standard English” will dismantle white supremacy, then you not paying attention! If we, as teachers, truly believe that code-switching will dismantle white supremacy, we have a problem. If we honestly believe that code-switching will save Black people’s lives, then we really ain’t paying attention to what’s happening in the world. Eric Garner was choked to death by a police officer while saying “I cannot breathe.” Wouldn’t you consider “I cannot breathe” “standard English” syntax? (p. ix)

This single paragraph captured gaps in my own personal experiences. From her, I learned about the history and elements of Black English. I learned Black English from my family and community, but I never knew it had a formalized structure or was considered a form of English and not just a dialect or vernacular until reading Baker-Bell (2020). Not a single professor in my English Education teacher education program exposed me to or taught me the history, rules, and elements of Black English. I was never given the formal academic support to think about the personal cost of code-switching, which meant my white classmates did not get support to think about the impact on their students.

The more I grapple with my emotions and trauma about my own experiences in English Education and with grammar, the clearer it becomes that code-switching causes trauma for Black people, especially in formal education settings. Black educators and children are encouraged to turn off aspects of who they are, that are deemed unprofessional, “ghetto,” or inappropriate. I internalized a belief that my language and grammar was inferior, and as such, I had to become someone else to be accepted.

I made the decision to provide explicit examples of what this looks like in the English language, so my students could be more thoughtful about their own word choice. As an example, the Western world has intentionally made everything black symbolize all that is evil and bad (e.g., black sheep, blacklist, Black Death, and black devil). Most symbols and words that are associated with white symbolize purity and cleanliness (e.g., white as snow, little white lie, and that’s very white of you). For this reason, the language used to describe Black bodies derives from disdain, disrespect, and devaluation of Black people (Johnson et al., 2017).

However, this issue is not only about words. As Dr. Baker-Bell (2020) indicated, this idea of speaking wME does not save Black adults and children from anti-Black violence. In an effort to heal from the trauma, I decided to teach using my mother’s tongue (Tan, 1990) to decentralize wME and dismantle anti-Blackness in the English Language: Grammar and Usage course.

When creating TikTok and screencasts on wME concepts for my students, I was purposeful with my own language patterns. For example, I taught the students the difference between phrases and clauses (see Video 2). I used the word “y’all” throughout the video, as it is a common word that is used in Black English. Furthermore, I used elements of Black English that go beyond word choice through my inflections and cadence and movements in my body and hands. Smitherman and Smitherman-Donaldson (1986), described this as “talkin’ & testifyin.’” Not only do Black people verbally talk and testify, but we also communicate with and through our bodies (Johnson 2019). I intentionally made the choice not to code switch in front of my students and to show them the beauty of Black English.

Video 2 Phrases and Clauses TikTok

I not only utilized my mother tongue when introducing the students to concepts, but in preparing them for the wME exams, using Jamboard and screencasts (see Video 3) that are mandated by the English Education program.

Video 3 Direct Objects Screencast

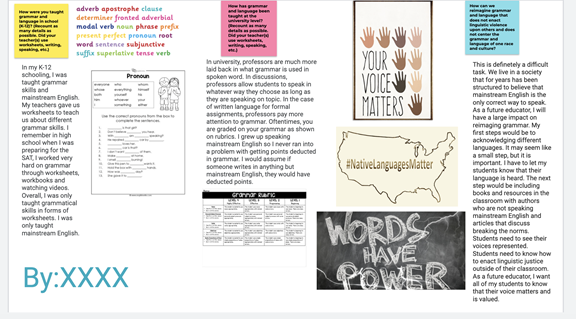

Another example of how wME is centered in grammar and language English Education courses is that the department mandates that students take exams focused on wME, but the students are not required to learn about other forms of grammar and language. Professors are left to deem them important or integrate them as a supplement to what is apparently superior knowledge. Furthermore, this practice continues to erase other languages and grammars. The students found that the TikTok and screencast were helpful in their understanding of wME; however, they did not comment on my Black English language use until I structured an assignment that required them to.

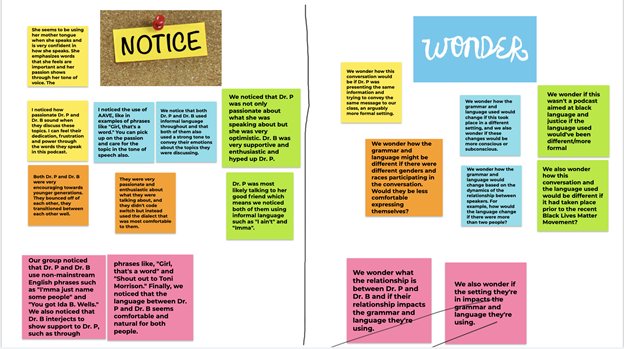

I designed an activity that required students to analyze the language and grammar heard on an episode of podcast “Black Gaze” (see Video 4), which another Black woman (Dr. Shamaine Bertrand) and I host. The structure of the activity allowed me to observe without intervening, and I heard students describe our language as “unprofessional.” They wondered if we would speak the same if we were in the presence of white people or in a professional setting.

Video 4 Black Gaze Podcast Snippet

I was prepared to hear such things but hearing their opinions about my language, and the language of Black people, left me feeling hypervisible and added to the spirit murdering (Love, 2019) and abuse Black faculty experience in white dominated spaces (Fujiwara & Roshanravan, 2018). This activity was the most challenging to facilitate, as it added to the trauma of people dehumanizing Black people, our language, and more specifically, my friend’s and my voices, hearts, and experiences. Their perspectives of the language use in the podcast serves as an example of the symbolic violence that transpires in classrooms where students and educators hold dehumanizing assumptions about the history, culture, and language of Black people (Johnson et al., 2017).

This experience demonstrated that Black language is disruptive to, or unwelcome in, academic spaces. People who speak Black English are constantly attacked as they are linguistically profiled, as my students profiled us for speaking the language of comfort, home, family, heritage, and friendship (Weldon, 2000). Despite decades of research that documents Black English as historic, literary, and rule governed (Alim & Smitherman, 2012; Baker-Bell, 2020), English Education courses participate in linguicide, or the killing of a language (Boutte, 2016), in programs. They do not require teacher education students to learn about Black Language, nor teach it to their students. Instead, it is viewed as slang, incorrect, or broken English, and Black people’s intelligence is questioned when they speak it (Wynter-Hote & Smith, 2020).

Through my purposeful use of Black language, I was able to demonstrate that we all understand one another, and there is no need to police language and create unnecessary barriers in the teaching of language and grammar. Although I can repeat this message in my instruction, students must come to their own understanding of how grammar and language should be taught in K-12 classrooms. I was able to help them expand their own understanding through the strategic use of apps and websites.

Technology as a Pedagogical Tool

Many of the students entered the course eager to learn the rules of wME grammar through workbook assignments and writing essays, which reflects what Jones and Okun (2001) described as the “worship of the written word,” an element of white supremacy. I intentionally utilized technology such as a PhotoVoice project and minidocumentary that pushed students to interrogate their understanding of wME and diverse languages rather than relying on the written word.

I used Jamboard to represent visually their perspectives and Twitter as a form of communication, collaboration, and discussion that allowed students to communicate in their mother tongue as opposed to a formalized discussion board. Researchers and educational practitioners have agreed that technology can be harnessed as a pedagogical tool both to assist and expand student learning capabilities and develop multiple literacies (Buckley-Marudas & Martin, 2020; Leu et al., 2009; Smith, 2017; Vu et al., 2019).

PhotoVoice and Minidocumentary. The students interrogated their wME grammar experiences, perceptions of people of color grammars and usage, and reimagined how grammar should be taught and applied in K-12 ELA classrooms and English Education programs. Although we discussed people of color grammars and usage, we specifically zoned in on Black English. The students reflected using PhotoVoice (Bazemore-Bertrand & Handsfield, 2019; Wang & Burris, 1997; Zenkov et al., 2014) and created a minidocumentary to demonstrate how their perceptions changed about wME grammar throughout the course.

PhotoVoice is a visual method used to assist adult educators in connecting their prior school experiences to their current attitudes and behaviors toward teaching (Bazemore-Bertrand & Handsfield, 2019). It is the use of photography, reflection, and discussion as tools for social change. Within the PhotoVoice assignment, students captured photographs and engaged in written, audio, and visual reflection using the Padlet, based on the questions posed (Figure 2). PhotoVoice is an example of multimodal learning, as it utilizes video, audio, sound elements as unique modes of communication and ways to interpret physical and virtual worlds, the relationships between people, and how they experience certain spaces (Buckley-Marudas & Martin, 2020).

Figure 2 PhotoVoice Reflection Questions in Padlet

The reflection questions examined the ethical, social, mental, physical, and political consequences of enacting linguistic violence in English Education programs and K-12 ELA classrooms. This critical reflection brought commonly held beliefs about grammar and language into question (Sydnor et al., 2020). The PhotoVoice assignment created tension and cognitive dissonance for the students related to their unwillingness at the beginning of the course to confront the conflict between their purported beliefs about grammar and language. The students demonstrated their reflections and how their perspectives of grammar and language changed throughout the course, by creating a minidocumentary to present to the class. This assignment was also an opportunity to dismantle white supremacy within the course, as opposed to the students merely writing a paper about it.

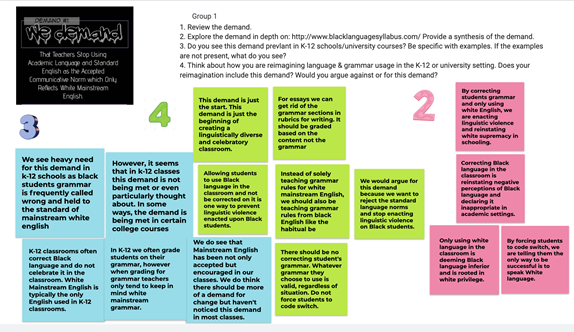

JamBoard. The PhotoVoice project required students to reflect on grammar and language. They were given scaffolded assignments throughout the course that provided more opportunities to dig deeper about their own personal experiences, their perceptions, and what reimagining grammar and language instruction in K-12 ELA classrooms and the English Education program would look like. Due to the virtual environment, students worked collaboratively through these topics using Jamboard, a Google app. Users can sketch their ideas using images, notes, sticky notes, pens, and text. Four course assignments provided the opportunity for the students to dig deeper into these topics using Jamboard: Cycle of Socialization, Perceptions of People of Color, Reimagining Grammar and Language Instruction, and Linguistic Demands (Baker-Bell & Kynard, 2020).

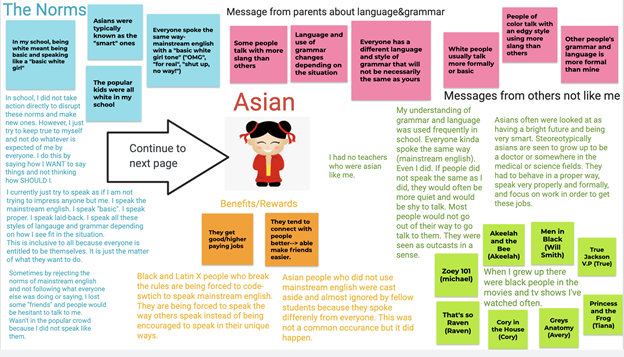

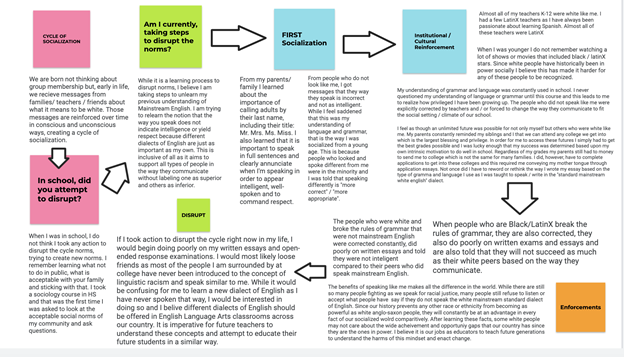

Cycle of Socialization: Archeology of Self. The cycle of socialization assignment pushed students to explore the ways in which they have been socialized to center wME. In the PhotoVoice reflection the students barely scratched the surface about their personal experiences with grammar and language but were able to go deeper on the JamBoard task (Figure 3). This assignment is an example of Sealey-Ruiz’s (2018) archeological dig, in which students had to begin the course with the work of unpacking their own identity and experiences with grammar and language as, without it, they would not be able to identify how they have enacted or perpetuated anti-Blackness linguistic violence within their own lives.

Figure 3 Student Sample of Cycle of Socialization

Perceptions of Diverse Grammars and Languages. Once students were able to begin the journey of interrogating their own identities and experiences with grammar, language, anti-Blackness and linguistic violence, they were ready to explore the assets of diverse grammars and languages and the conditions created in ELA and English Education classrooms and society at large that enact linguistic violence. Students dug deeper into this element of the course in a collaborative assignment using Jamboard.

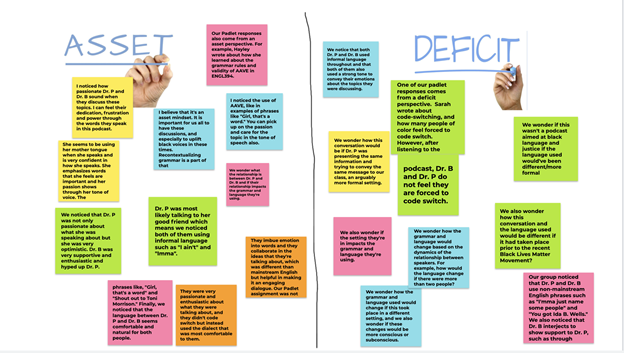

Students were asked to listen to the excerpt from the Black Gaze podcast, and write down what they noticed and wondered about the language of the cohosts. The students characterized the language and grammar as informal and racialized (Figure 4). In this context I was able to convey to students that their perceptions of Black English reflected a deficit perspective (Figure 5).

Figure 4 Student Analysis of Black Gaze Podcast Cohosts’ Language and Grammar

Figure 5 Deficit Perspectives of Black Gaze Cohost’s Language and Grammar

Reimagining Grammar and Language Instruction. Once students started the journey of interrogating their own experiences with grammar, language and anti-Blackness and exploring diverse grammars and languages, they started to reimagine grammar and language instruction in English Education programs and K-12 ELA classrooms. Students used Jamboard to visualize linguistic justice in English classrooms. One assignment simply asked them to reimagine what linguistic justice would look like in action (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Student Sample: Reimagining Grammar and Language in English Education Programs and K-12 Classrooms

Students were expected to begin this reimagination based on the texts we read throughout the course. Once they tapped into their own imagination, they were exposed to the linguistic demands (Baker-Bell & Kynard, 2020; Figure 7). The purpose of these assignments was to move from just talking about linguistic justice to envisioning what it would look like in action, informed by voices of Black people talking and writing about the demands for linguistic justice.

Figure 7 Baker-Bell and Kynard (2020) Linguistic Justice Demands Student Analysis

Twitter Chats

Many educators in the 21st century use various forms of technology and social media as part of their daily teaching practices and as part of their personal lives (Adjapong et al., 2018). However, many teacher education programs have struggled to incorporate it as a teaching practice or learning tool. Some are holding on to learning management systems designed for the ease of the instructor rather than the benefit of student learning.

For the past 3 years, I have facilitated Twitter chats using the hashtag #TeacherEduMatters, because of the opportunities for enhanced relationships within classes. Twitter chats provide a virtual space for engagement and reflection (Krutka et al., 2014), the opportunity to summarize key points (Kruta & Damico, 2020), and support and collaborative learning (Voorn & Kommers, 2013). Twitter chats also provide the opportunity for mentoring (Curran & Chatel, 2013), developing teacher identities (Carpenter et al., 2017), and even challenging preservice teachers to interrogate their positionalities (Cook & Bissonnette, 2016).

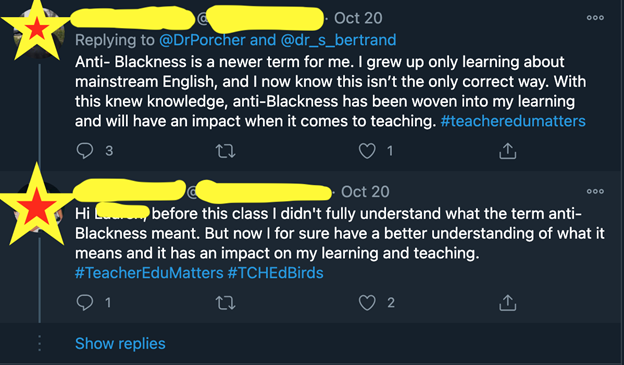

More specifically, in our Twitter chats, the students were given the opportunity to collaborate with preservice teachers and faculty members at Illinois State University and Rutgers University Graduate School of Education. Utilizing Twitter as a discussion tool expanded students’ interrogation of language, grammar, and anti-Blackness beyond the students in the course.

Students were expected to create Twitter accounts for the course to engage in the Twitter chats. They were positive about the potential of professional Twitter use but sometimes struggled with the mechanics and knowledge required for Twitter chat participation (as also noted by Hsieh, 2017). Twitter was a challenge because, although students were familiar with the technology being used, the use as a pedagogical tool is characteristically different from personal use. Using technology resourcefully throughout the teaching processes allows preservice teachers to use their personal technologies for a continuous transition into the classroom (Buckley-Marudas & Martin, 2020). Centering Blackness through the text selection, in my language, and through pedagogical tools impacted students’ criticality of anti-Blackness in English Education and K-12 schools.

Research Question 2: Students’ Criticality of Anti-Blackness in English Education & K-12 Classrooms

In answer to Research Question 2, I found that students’ criticality was increased by the four following key themes:

- Disruption

- Awareness

- Interrogation

- Action

Disruption

I had accepted that my students would be uncomfortable by my purposeful efforts to disrupt the norm of whiteness in education. In teacher education programs, whiteness is reflected in the lack of faculty of color, lack of students of color, curricula, teaching and assessment practices, teacher-student interactions, decision-making, and more, like the consistent privileging of the interests, values, accomplishments, histories, and more of whites (Harris et al., 2020). While the texts I used served to center Blackness in the written word, my presence as their professor, a Black woman, disrupted their mental models of home, school, and college as all white spaces.

Many of the students indicated in assignments, discussions, and reflections that they had never had a Black teacher or professor and that what I was asking them to do was different than anything they had experienced before. Using Jamboard, students completed a cycle of socialization for their experiences with grammar, language, and anti-Blackness. I explicitly asked them to identify if all of their teachers were white like them and spoke like them. Their responses indicated that simply by being their professor and redesigning the syllabus, I had disrupted the overwhelming whiteness of their formal educational experiences (see Figure 8).

Figure 8 Course Jamboard Assignment: Cycle of Socialization

To maintain the disruption, I made a purposeful decision to center their PhotoVoice assignment on Blackness and asked them to address the following question: “What do you know about the home grammar(s) and language of Black and Brown people/students? Where do you see the language and grammar(s) of Black and Brown people used?” Not a single student mentioned a personal relationship with a Black or Brown person. None of them were able to pull on the experience of being inside a Black or Brown family’s home. They all drew from the media or stereotypes for their answer.

As a follow-up question I asked, “Do you have any personal experiences with Black and Brown people?” (see Figure 9) The answer was again, a resounding, “No.” Cognitively, I recognized that non-Black students with limited personal experiences with Black people will develop negative perceptions of Black people. Emotionally, it was a reminder of my own trauma, to recognize their negative perceptions (Porcher, 2020). In some cases, it was clear that by interacting with me, they were having sustained direct and personal interactions with a Black woman for the first time in their lives.

Figure 9 PhotoVoice Reflection

In addition to organizing the course around one particular text, I used the FBLT framework to organize the flow of activities. I carefully curated a PhotoVoice reflection to ensure students would engage in their own archeology of the self. The centering of Blackness in the language and grammar course was a deliberate disruption to their norm of the dominance of whiteness. It was clear the students were not aware of anti-Blackness and the way it shows up in language and grammar. A Black professor centering a text written by a Black author disrupted the dominance of whiteness and raised students’ awareness of anti-Blackness in language and grammar and instruction.

Awareness

My students were too young to remember the debate about Ebonics in the 1980s and 1990s. Due to the dominance of whiteness in their schools and communities, most were unaware of anti-Blackness in language and grammar instruction. The students stated in classroom and Twitter discussions that they spoke wME because that is what their parents told them was correct and the standard.

By designing the course to define and highlight anti-Blackness in wME as well as the richness of Black English, their mental models changed (see Figure 10). A student observed in a course paper, “If a Black student that speaks Black Language with family and friends every day can be unaware of their internalized Anti-Black Linguistic Racism, then one can only imagine how clueless white students are about racism and linguistic violence in the classroom, let alone society at large.” The course raised their awareness, specifically the integration of technology as a pedagogical tool, of wME as a form of linguistic violence and anti-Blackness.

Figure 10 Student Twitter Response

Interrogation

Students experienced cognitive dissonance as they realized the mandate of wME in classrooms and society was a form of anti-Blackness and linguistic violence. They struggled to reckon with the fact that their parents, teachers, and English Education program had taught them to enact harm upon others. Throughout their PhotoVoice assignments, I consistently questioned their use of language to describe diverse language as informal, ghetto, broken, or slang (see Figure 11).

Figure 11 Questioning to Push Students to Interrogate Knowledge

The questioning forced them to think deeper about the labels they used to describe diverse grammars and language, which elevated wME as the standard. Students shared these sentiments in their analysis essays. For example, “It wasn’t until taking this course and being asked ‘what is “academic language,’” or ‘what does “professional” mean’ that I realized I didn’t know as much as I liked to think I did.”

The students learned these negative perceptions of Black language and grammar in church, extracurricular activities, play, and school via experiences and curriculum that overwhelmingly featured white characters, white-dominated events, and white centric texts (as found by Miller, 2005). Through the assignments students were consistently asked to interrogate the role of white dominance in shaping the only life that they have known. The questioning also increased their criticality. It was not enough for the students only to discuss and analyze language, grammar, and anti-Blackness in English Education programs and K-12 ELA classrooms, but to move toward linguistic justice. They understood the work did not stop at the interrogation and were propelled to action.

Action

The course was designed for students to reimagine the ways in which grammar and language could be taught in the English Education program and K-12 schools that does not enact linguistic violence. Simply put, as future teachers, how would they enact linguistic justice in their personal lives and as future educators? This theme and step are imperative, as with 400+ years of enslavement of Black people, it is time to shift from required texts, task forces, and committees to consciousness, activism, actions and policies that will dismantle anti-Blackness (Johnson, 2018).

In the assignments, discussions, and activities, the students identified actions that they could take to address anti-Blackness and linguistic violence. This aspect of the course was most impactful and joyous for me, as the students could shift from only talking about anti-Black linguistic violence to understanding their power in dismantling these systems in ELA K-12 classrooms and English Education programs. Some examples students discussed in their analysis essays are stated in the appendix. Students utilized the texts from the course and pedagogical technology tools to propel into action as future teachers.

Discussion and Implications

Centering Blackness in an English Education course is possible. It needs to be stated plainly that this centering is hard work for everyone involved, especially the professor, especially if the professor is a Black woman, as it requires pulling teacher education away from Eurocentric frameworks and centering Blackness. Moving from talking about reimagining English Education to action is personal for me. The trauma I felt, as described in the opening, is one of many, but sadly not uncommon.

To structure the course so that it ameliorated and prevented future harms to children, I had to be thoughtful about each move and decision. English Education programs must consider the racial fatigue and spirit-murdering (Love, 2019) from teaching language and grammar courses where Blackness is typically invisible (e.g., in content, curriculum, and pedagogy) yet hypervisible (e.g., in wME), as well as begin to consider instructional practices that actively stand against the physical and symbolic violence perpetrated against Black bodies (Johnson 2018). I was expected to teach and not see myself or my culture reflected in what the previous professors considered knowledge, not to mention my hypervisibility as the only Black person in our virtual classroom focused on teaching wME.

In the discussion for reimagining education, it has been acknowledged that children are being miseducated. It is up to teacher educators to facilitate teaching and learning experiences that provide the opportunity for preservice teachers to unlearn and undo the dominant narratives that include distorted beliefs about Blackness and false beliefs about the purity of whiteness (Johnson, 2019), before they enter the classroom and enact further violence and harm.

With this in mind, the following are some implications for teacher educators to utilize technology as a pedagogical tool to enact linguistic justice within English Education by centering Blackness. Thus, while I attend in many ways to the Eurocentric parameters of American Psychological Association requirements for professional papers, in the following section I use words and concepts from Black culture, including Black English (Wynter-Hote & Smith, 2020), to frame how teacher educators can center Blackness.

- Pull up. Many of the students discussed that I was the only faculty member that exposed them to anti-Blackness, or told them the truth about grammar and language. Black people cannot be the only people doing this work. Active participation in this work must be a goal for all English Education teacher educators.

- Tell the truth, shame the devil. Teacher educators must explicitly teach the truth about the history of ELA content and the current relationship between literacy, language, race, and education by expanding the concept of literacies (Johnson, 2019).

- Decolonize your syllabus. Adding Black folx to the syllabus is not enough. Get us off the margins and center our text, art, media texts, theorists, and pedagogical practices. Don’t treat us as passive subjects but help students apply the knowledge found in our texts.

- It’s the tech for me. The students’ creativity and criticality increased when I not only centered Blackness, but I provided opportunities for students to express themselves using different modalities. Worshipping the written word is an element of white supremacy. Continue to stay abreast of technology that is used in K-12 classrooms, and use it in your course. How do teacher educator prepare preservice teachers for future classrooms but do not mirror the K-12 classrooms? Make it make sense!

Centering Blackness in English Education programs requires soul work (Johnson, 2017). Soul work requires me to dig deep and do introspective work about who I am as a Black faculty member, how I show up in white dominated spaces, and even how I share my thoughts and research in articles like this. Furthermore, it reminds me of my moral responsibility to demonstrate that Black Lives Matter, not just say it. I bring my whole self (ves) to this space because I know what happens when teacher educators do not do this work. We enact harm upon our preservice teachers. Then our preservice teachers enter the classroom and perpetuate anti-Black violence. They police Black children for just being Black children.

All around the world, people are marching and advocating for the humanity of Black lives. For many Black Americans, this is a day of reckoning, but we also understand, based on history, that marching is just the beginning. We need and must have actual policy changes that accompany our words. Doing our part in English Education to center the lives, experiences, cultures, and work of Black people in our programs as the foundation will demonstrate that Black Lives Matter, in action.

References

Adjapong, E. S., Emdin, C., & Levy, I. (2018). Virtual professional learning network: Exploring an educational twitter chat as professional development. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 20(2), 24-39.

Alim, H. S., & Smitherman, G. (2012). Articulate while Black: Barack Obama, language, and race in the U.S. Oxford University Press.

Appleget, C., Shimek, C., Myers, J., & Hogue, B. C. (2020). A collaborative self-study with critical friends: Culturally proactive pedagogies in literacy methods courses. Studying Teacher Education, 16(3), 286-305. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2020.1781613

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge.

Baker-Bell, A., & Kynard, C. (2020, December 19). This ain’t another statement! This is a DEMAND for Black linguistic justice! Black Language Demands. http://www.blacklanguagesyllabus.com/black-language-demands.html

Bazemore-Bertrand, S., & Handsfield, L. J. (2019). Show and tell: Elementary teacher candidates’ perceptions of teaching in high-poverty schools. Multicultural Education, 26(3/4), 27-37.

Bertrand, S. K., & Porcher, K. (2020). Teacher educators as disruptors redesigning courses in teacher preparation programs to prepare white preservice teachers. Journal of Culture and Values in Education, 3(1), 72-88.

Boutte, G. S. (2016). Educating African American students: And how are the children? Routledge.

Buckley-Marudas, M. F., & Martin, M. (2020). Casting new light on adolescent literacies: Designing digital storytelling for social justice with pre-service teachers in an English language arts education program. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 20(2), 242-268. https://citejournal.org/volume-20/issue-2-20/english-language-arts/casting-new-light-on-adolescent-literacies-designing-digital-storytelling-for-social-justice-with-preservice-teachers-in-an-english-language-arts-education-program

Carpenter, J. P., Cook, M. P., Morrison, S. A., & Sams, B. L. (2017). “Why haven’t I tried Twitter until now?”: Using Twitter in teacher education. Learning Landscapes, 11(1), 51-64.

Carpenter, J. (2015). Preservice teachers’ microblogging: Professional development via Twitter. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 15(2), 209-234. https://citejournal.org/volume-15/issue-2-15/general/preservice-teachers-microblogging-professional-development-via-twitter

Cook, M. P., & Bissonnette, J. D. (2016). Developing preservice teachers’ positionalities in 140 characters or less: Examining microblogging as dialogic space. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 16(2), 82-109. https://citejournal.org/volume-16/issue-2-16/english-language-arts/developing-preservice-teachers-positionalities-in-140-characters-or-less-examining-microblogging-as-dialogic-space

Curran, M. B., & Chatel, R. G. (2013). Virtual mentors: Embracing social media in teacher preparation programs. In J. Keengwe (Ed.), Pedagogical applications and social effects of mobile technology integration (pp. 258-276). IGI Global.

Derman-Sparks, L., & Ramsey, P. G. (2006). What if all the kids are White? Engaging White children and their families in anti-bias/multicultural education. Teachers College Press.

Dumas, M. J., & ross, k. m. (2016). “Be real Black for me”: Imagining BlackCrit in education. Urban Education, 51(4), 415–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916628611

Emdin, C. (2016). For White folks who teach in the hood… and the rest of y’all too: Reality pedagogy and urban education. Beacon Press.

Fujiwara, L., & Roshanravan, S. (2018). Introduction. In L. Fujiwara & S. Roshanravan (Eds.), Asian American feminisms & women of color politics (pp. 3–24). University of Washington Press.

Harris, B. G., Hayes, C., & Smith, D. T. (2020). Not a ‘who done it’ mystery: On how Whiteness Sabotages equity aims in teacher preparation programs. Urban Review, 52, 198-213,

Harro, B. (2000). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, R. Castaneda, H. Hackman, M. Peters. & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 16-21). Routledge

Hernández-Saca, D. I., Martin, J., & Meacham, S. (2020). The hidden elephant is oppression: Shaming, mobbing, and institutional betrayals within the academy—Finding strength in collaborative self-study. Studying Teacher Education, 16(1), 26-47.

Howard G. R. (1999). We can’t teach what we don’t know: White teachers, multiracial schools. Teachers College Press.

Hsieh, B. (2017). Making and missing connections: Exploring Twitter chats as a learning tool in a preservice teacher education course. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 17(4), 549-568. https://citejournal.org/volume-17/issue-4-17/current-practice/making-and-missing-connections-exploring-twitter-chats-as-a-learning-tool-in-a-preservice-teacher-education-course

Johnson, L. L. (2019). I had to die to live again: A racial storytelling of a Black male English educator’s spiritual literacies and practices. In M. M. Juzwik, J. C. Stone, K.J. Burke, & D. Davila, (Eds.), Legacies of Christian languaging and literacies in American education (pp. 205-221). Routledge.

Johnson, L. L. (2018). Where do we go from here? Toward a critical race English education. Research in the Teaching of English, 53(2), 102-124.

Johnson, L. L., Jackson, J., Stovall, D. O., & Baszile, D. T. (2017). Loving Blackness to death: (Re)imagining ELA classrooms in a time of racial chaos. English Journal, 106(4), 60.

Jones, K., & Okun, T. (2001). White supremacy culture. Dismantling racism: A workbook for social change groups. Change Work.

Kitchen, J. (2020). Attending to the concerns of teacher candidates in a social justice course: A self-study of a teacher educator. Studying Teacher Education, 16(1), 6-25.

Krutka, D. G., & Damico, N. (2020). Should we ask students to Tweet? Perceptions, patterns, and problems of assigned social media participation. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 20(1), 142-175. https://citejournal.org/volume-20/issue-1-20/general/should-we-ask-students-to-tweet-perceptions-patterns-and-problems-of-assigned-social-media-participation

Krutka, D. G., Bergman, D. J., Flores, R., Mason, K., & Jack, A. R. (2014). Microblogging about teaching: Nurturing participatory cultures through collaborative online reflection with pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 83-93.

La Boskey, V. (2004). Moving the study of self-study research and practice forward: Challenges and opportunities. In J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International hand-book of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817–869). Kluwer.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2016). “# Literate lives matter” Black reading, writing, speaking, and listening in the 21st century. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 65(1), 141-151.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491.

Leu, D. J., O’byrne, W. I., Zawilinski, L., McVerry, J. G., & Everett-Cacopardo, H. (2009). Comments on Greenhow, Robelia, and Hughes: Expanding the new literacies conversation. Educational Researcher, 38(4), 264-269.

Loughran, J. (2014). Professionally developing as a teacher educator. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 271-283.

Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Miller, E. (2015). Discourses of Whiteness and Blackness: An ethnographic study of three young children learning to be White. Ethnography and Education, 10(2), 137–153.

Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice, 31(2), 132-141.

Morrison, T. (1994). Playing in the dark. Vintage.

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic Incorporated.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93-97.

Porcher, K. (2020). Teaching while Black: Best practices for engaging white pre-service teachers in discourse focused on individual and cultural diversity in urban schools. Journal of Learning, Teaching & Research, 15(1), 116-134.

Porcher, K., & Bertrand, S. (Host). (2020, September 23). Protect Black Womxn. (Season 2, Episode 1). In Black Gaze Podcast, Paine Artistry. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/protect-black-womxn/id1512508384?i=1000492203572

Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2011). Dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline through racial literacy development in teacher education. Journal of Curriculum & Pedagogy, 8(2), 116-120. doi:10.1080/15505170.2011.624892

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2013). Building racial literacy in first-year composition. Teaching English in the Two Year College, 40(4), 384-398.

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2018, January 5). Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz: The archaeology of the self [Video]. https://vimeo.com/299137829

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2020). Arch of self, LLC. https://www.yolandasealeyruiz.com/archaeology-of-self

Sharkey, J. (2018). Who’s educating the teacher educators? The role of self-study in teacher education practices (S-STEP) in advancing the research on the professional development of second language teacher educators and their pedagogies. Ikala, Revisita de Lenguaje y Cultura, 23(1), 15-18. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v23n01a02

Smith, B. E. (2017). Composing across modes: A comparative analysis of adolescents’ multimodal composing processes. Learning, Media and Technology, 42(3), 259-278.

Smitherman, G., & Smitherman-Donaldson, G. (1986). Talkin and testifyin: The language of Black America (Vol. 51). Wayne State University Press.

Sydnor, J., Daley, S., & Davis, T. (2020). Video reflection cycles: Providing the tools needed to support teacher candidates toward understanding, appreciating, and enacting critical reflection. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 20(2), 369-391. https://citejournal.org/volume-20/issue-2-20/current-practice/video-reflection-cycles-providing-the-tools-needed-to-support-teacher-candidates-toward-understanding-appreciating-and-enacting-critical-reflection

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Tan, A. (1990). Mother tongue. The Threepenny Review, 43(7).

Voorn, R. J., & Kommers, P. A. (2013). Social media and higher education: Introversion and collaborative learning from the student’s perspective. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 1(1), 59-73.

Vu, V., Warschauer, M., & Yim, S. (2019). Digital storytelling: A district initiative for academic literacy improvement. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 63(3), 257-267.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387.

Warren, C.A., & Coles, J.A. (2020): Trading spaces: Antiblackness and reflections on Black education futures. Equity & Excellence in Education, 53(3), 382-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2020.1764882

Weldon, T. L. (2000). Reflections on the Ebonics controversy. American Speech, 75(3), 275– 277.

Wynter-Hoyte, K., & Smith, M. (2020). “Hey, Black Child. Do you know who you are?” Using African Diaspora literacy to humanize Blackness in early childhood education. Journal of Literacy Research, 52(4), 406-431.

Zeichner, K. (2007). Accumulating knowledge across self-studies in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1), 36-46.

Zenkov, K., Ewaida, M., Bell, A., & Lynch, M. (2014). Picturing English language learning youths’ and pre-service teachers’ perspectives on school: How “photovoice” projects might inform writing curricula and pedagogies for diverse youth. In LIST EDITORS AS PER APA (Eds.), Exploring multimodal composition and digital writing (pp. 332-349). IGI Global.

Appendix

Student Reimagination of Language and Grammar Instruction

Student 1

In order to create a truly inclusive classroom that does not enact linguistic violence, educators cannot stop at decentering whiteness. They must actively incorporate diverse grammars and authors, as well as texts in different languages, into the curriculum. When students see themselves and their language(s) represented in their schoolwork, it makes them feel confident, capable, and encourages them to dream bigger.

Student 2

However, the onus is not entirely on educators. As a student in the modern world, I have been given the unique opportunity to learn, grow, and cultivate knowledge from anyone, anywhere, at any time. I have the choice to remain in my comfort zone and ignore uncomfortable topics, or I can choose to be educated on something bigger than myself and use that knowledge to help those that do not have the privilege of choice. It is not enough to sit back and blame society in the name of “setting kids up for success.”

Student 3

First, it is necessary to explore “grammar” as a concept. This process will begin with the students’ reflections of what grammar is to them. They will clearly outline their beliefs about English, grammar, and usage. Throughout this process, I will challenge their beliefs by continuing to ask for further explanations. Students will also be encouraged to challenge their peers using the same process. The most important question during this process will be “why?” With this, I hope that students begin to recognize the ideas about language that they have been socialized to believe and the systems in the US that affect and are affected by language beliefs.

Student 4

As such, the next unit of my reimagined ELA classroom will focus on the development of various grammars, beginning with White mainstream English. Through this process, students will learn that the development of standardized grammar was largely rooted in classism and White supremacy. Furthermore, they will discover that most of the language rules they were socialized to believe are arbitrary. To continue, students will learn about the development of diverse grammars as well. This will not only hold other grammars to the same regard as mainstream grammar in order to center the culture of all students, but it will also provide information that is crucial for understanding the importance of other grammars and developing anti-racist learners. For example, students will learn that Black English is a “rule-based language” that slaves, after being separated from those that shared their mother tongue, were able to develop with pieces of their native languages in order to communicate with each other (The Guide for White Women).

Student 5

First, the class as a whole must agree to give anyone and everyone the right to speak freely. Students should not feel stress due to the use of their mother tongue, attempts at utilizing White mainstream grammar, or translanguaging. By allowing students that speak minoritized English grammars to implement their native tongue, they are able to focus on the meaning behind their words in order to promote greater expression and in-depth discussion, while also fostering positive cultural identities by legitimizing the language that is associated with their home cultures (Christensen)

Student 6

To start, classrooms, whether K-12 or at the University level, must understand and teach the histories of diverse grammars, such as Black Language. Many people, including speakers of Black Language, are unaware of its origin and significance.

Student 7

Teachers should try to explore as many diverse languages as possible; this can be done through a unit where students are encouraged to explore different languages and/or dialects, such as Chicano English, Spanglish, Chinglish, Appalachian English, Cajun English, etc, and research their mechanics so that they may share what they have learned with the class.

Student 8

One way to combat linguistic violence in a English Language Arts classroom is to use a translanguaging stance. A translanguaging stance is a teacher’s belief that bilingual students have one holistic language repertoire (Garcia, 2017). In other words, a teacher who holds a translanguaging stance uses aspects of all languages a student speaks to assist them in their learning. Teachers with this belief view bilingualism as a tool and as a benefit in the learning process, not as a deficit. In a translanguaging English Language Arts classroom, students can not only read books by Black authors, but books that include Black Language. Students are also allowed to submit formal assignments using Black Language. A classroom that utilizes a translanguaging approach is different from a classroom that prioritizes code switching because a code-switching classroom deems Black Language inappropriate in certain situations, whereas a translanguaging classroom uses all languages at all times.

![]()